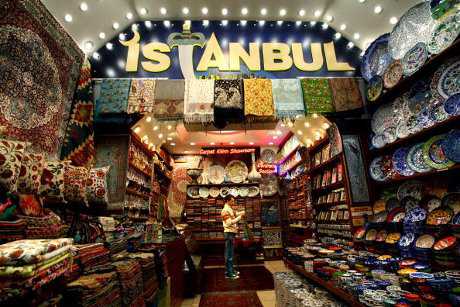

ISTANBUL. The name is magical, and all its old names, Byzantium and Constantinople, are magical too. They conjure up images of ancient civilizations, always fighting each other, and sometimes enriching each other. But in the end, they had to merge to leave a skyline that fascinates any visitor to this city, and a cultural wealth that takes any person’s breath away.

How does one not love those minarets? They may be somewhat ubiquitous but they never fail to catch one’s interest. How not to be awed by the Blue Mosque, Hagia Sophia, the Walls of Constantinople or the Archaeological Museum, and by the food?

How does one best describe this enchanting place where northern waters join southern seas, and where eastern paths separate from western roads? Is this where the East and the West assemble, or is this where the East and the West split?

Today, the answer does not seem important. Walking on an end-of-season late summer’s day down the famous and fabulous 3km-long promenade, Istiklâl Caddesi, from Taksim Square in the north down to the exciting Karaköy fish market beside the Golden Horn by the Galata Bridge, one is struck by how this sprawling city is Central Asian, Middle Eastern and Mediterranean, all at the same time.

It is Muslim, it is Orthodox Christian, it is Greek, and it is Roman. It is imperial.

Of Turkey’s 77 million people today, 15 million to 19 million live in Istanbul. This means that every fifth Turkish citizen resides in this city. And despite oversimplifying official figures telling us that as many as 99% of Istanbul’s residents are Sunni Turks, the profound ethnic mix is all too obvious.

In short, I am seeing before me not only the end product of 500 years of Ottoman ethnic integration, but that of many more centuries of painful intermingling before that. The names of ethnic groups and kingdoms mentioned in the amazing Istanbul Archaeological Museum, for example, and who existed in Anatolia and its surroundings, read like the Bible and more. Crusaders have been there, Vikings have been there. Huns, Persians, Arabs, you name it.

The proud faces one sees are not easy to place. For people living in what is always called a crossroad, they seem to belong so infinitely to the place though. This is a meeting place of civilisations, and as we know, civilisations do not always meet with open arms. Its history has been as much about war as anything else. But then, conflicts and contradictions do find common ground when covered by the sands of time.

At the moment, Istanbul exudes the modern pride of its Turkish inhabitants. Their recent economic growth has been miraculous. While East Asia buckled under its financial crisis in 1997/98, Turkey suffered its own only in 2001. This quickly led to financial and fiscal reforms that succeeded and saw the country grow at an annual average of 6% after that. 2009 was a bad year when the economy actually contracted, but since then the rebound has been dramatic. The Turkish GDP grew by 9% in 2010 and by 8.5% in 2011.

There were fears of the current account deficit amounting to 10% of GDP, and the inflation rate going above 10% earlier this year. The property market has also worried observers, who see a housing glut happening. This is, however, not like the asset bubble situation in Ireland or other European Union countries.

Definite signs of a slowdown this year have been welcomed by the authorities, who are hoping for an economic soft landing. But the general optimism remains high. For example, the first eight months of this year saw 6.2 million foreign visitors live in Istanbul’s many hotels, eat in its fragrant restaurants, and walk its busy streets. This is 18% more than in the same period last year.

And we are talking only about foreigners, most of whom were Germans abandoning their traditional holiday spots in Greece for the fresher and more affordable exoticism of Istanbul. Domestic tourism figures, if available, would be much more daunting.

The interest of Germans in Turkey is not unexpected since 10.1% of Turkish exports go to them. This figure is nicely balanced by 9.5% where imports are concerned. Turkey’s other major trading partners are Russia and China.

I digress. I had meant to write a travel piece on Istanbul, but it is difficult not to try to capture something of the economic optimism permeating the streets of this city that is now a successful modern Muslim-majority economy where half the work force is in services, a quarter is in agriculture and the rest in industry.

But back to impressions of Istanbul. A simple two-hour boat trip up the Bosporus alone is mind-boggling. One gets a better idea of how big the city actually is, how it stretches across both sides of the waters, and how it is joined by gigantic bridge after gigantic bridge.

Political troubles at distant borders seem far away, and one senses the cultural and geographic — and geopolitical — vastness that Turkey still commands today. One also feels how it will be the centre of an influential Turkic world that stretches from the hills of Istanbul to the mountains of China.

At the same time, despite the continental expanse, one is reminded that modernity — if I may use that much maligned word loosely here — is an urban process. But it is an urban process that is just the latest in a string of urban processes.

It is faster today perhaps, and draws on impulses from further away perhaps, but it is still an urban process of creating wealth and value through commercial and cultural interaction with other cities and peoples of our diverse world. The intermingling continues.

via How history never ends.