Dear UBI Advocates,

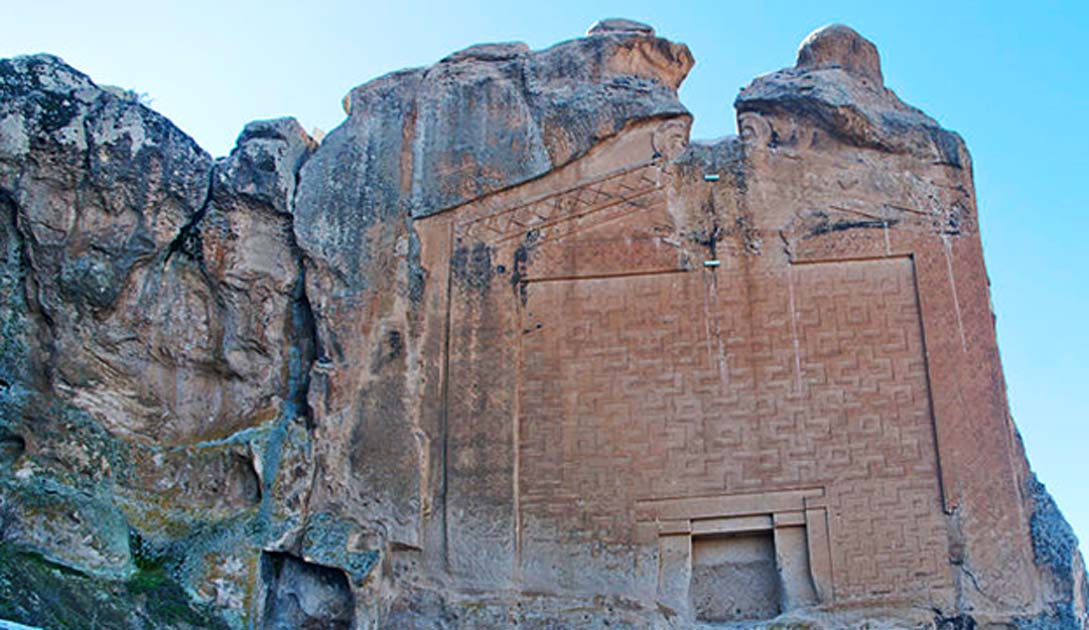

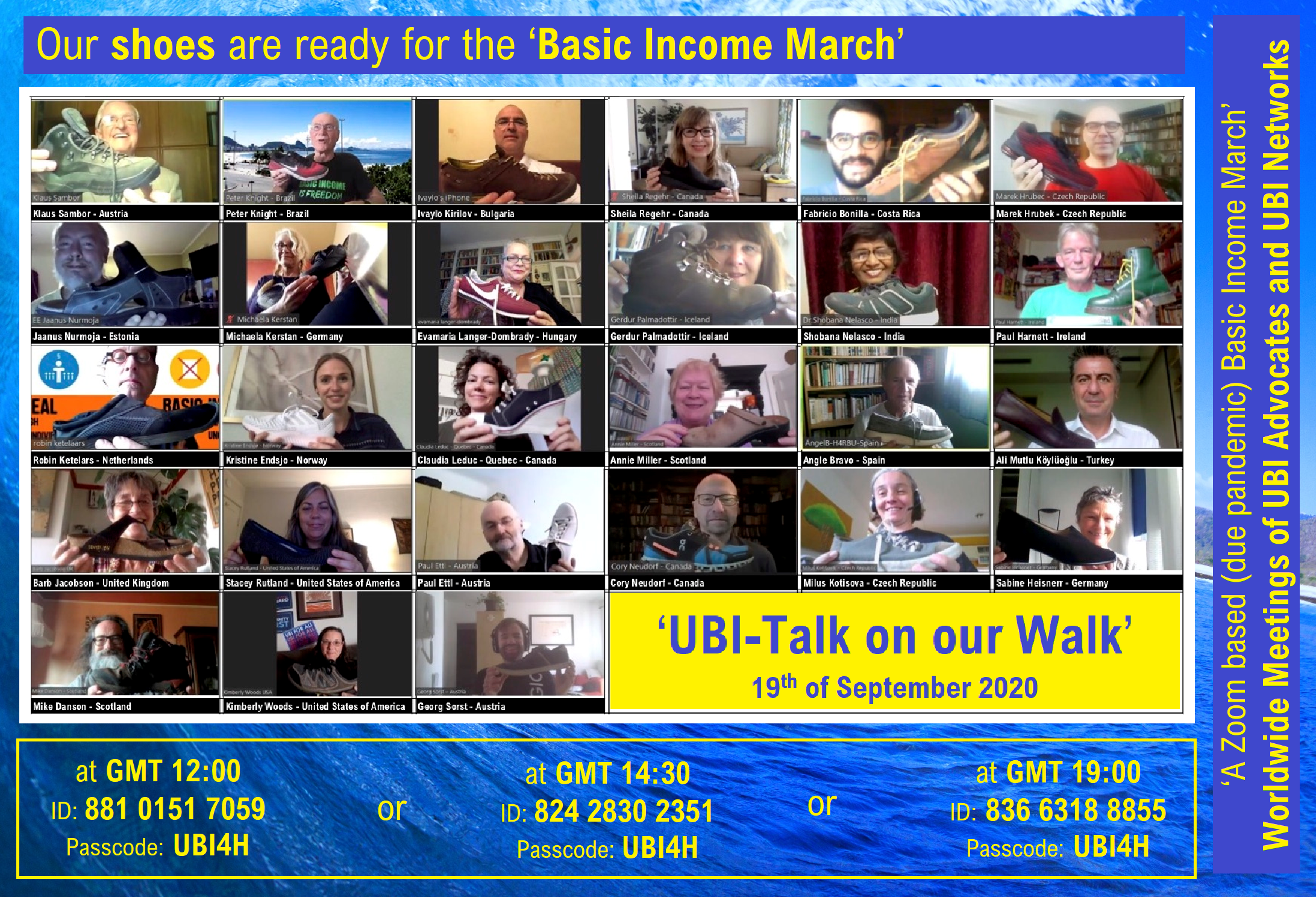

We would like to invite and hope to see all UBI Advocates, together with their friends and networks, at the ‘UBI-Talk on our Walk’;

- a Zoom based (due pandemic) Basic Income March,

- facilitated by ‘Worldwide Meetings of UBI Advocates and UBI Networks’,

- organized by UBI Networks,

- on 19th of September 2020, Saturday,

- at GMT 12:00, or at GMT 14:30, or at GMT 19:00,

- as a participation in the 2nd Basic Income March (an initiative by; Income Movement),

- during the 13th International Basic Income Week.

(Please, see attached two slides.)

Please take a shoe of yours with you for the screen shots in groups.

All the screen shots (photos) will be used for promotion of the UBI idea.

During the events, as time permits, limited number of participants may also give their short messages regarding UBI.

Please, kindly participate in one of the below (at the end of this message) listed Zoom Meetings.

We would like to thank our dear friends Alexander de Roo (Netherlands), Claudia Leduc (Canada), Peter Knight (Brazil) and Ali Mutlu Köylüoğlu (Turkey) for their contributions during development of this project, and to our dear friends Gerdur Palmadottir (Iceland) for her proposal regarding the title of the event (‘UBI-Talk on our Walked’) and Gaylene Middleton (New Zealand) for seconding the proposal.

Special thanks to the our dear friends, Klaus Sambor (Austria), Peter Knight (Brazil), Ivaylo Kirilov (Bulgaria), Sheila Regehr (Canada), Fabricio Bonilla (Costa Rica ), Marek Hrubek (Czech Republic), Jaanus Nurmoja (Estonia), Michaela Kerstan (Germany), Evamaria Langer-Dombrady (Hungary), Gerdur Palmadottir (Iceland), Shobana Nelasco (India), Paul Harnett (Ireland), Robin Ketelars (Netherlands), Kristine Endsjo (Norway), Claudia Leduc (Quebec, Canada), Annie Miller (Scotland), Angle Bravo (Spain), Ali Mutlu Köylüoğlu (Turkey), Barb Jacobson (United Kingdom), Stacey Rutland (United States of America), Paul Ettl (Austria), Cory Neudorf (Canada), Milus Kotisova (Czech Republic), Sabine Heisnerr (Germany), Mike Danson (Scotland), Kimberly Woods (United States of America), and Georg Sorst (Austria) for participation of them in the invitation message with their screen shots (photos).

The timing of our Zoom meetings are all announced as GMT (Greenwich Mean Time).

All the meetings will be recorded and will be shared partially or fully, especially for other UBI Advocates, who were not able to participate.

Our capacity for the Zoom meetings is 500 participants and in case the sessions are full, please see the Facebook page “UBI Advocates and UBI Networks” for additional meetings (in addition to the below listed pre-scheduled ones.)

Hoping to see all UBI Advocates, together with their friends and networks, at the ‘UBI-Talk on our Walk’,

All the Best,

Worldwide Meetings of UBI Advocates and UBI Networks

>>> Details of the Scheduled Zoom Meetings on 19th of September, 2020, Saturday :

at GMT 12:00

Meeting ID: 881 0151 7059

Passcode: UBI4H

at GMT 14:30

Meeting ID: 824 2830 2351

Passcode: UBI4H

at GMT 19:00

Meeting ID: 836 6318 8855

Passcode: UBI4H