UN Peacekeeping Operations in Central African Republic: The Legality- Legitimacy Paradox

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Gonca Oğuz GÖK Marmara Üniversitesi

Assist. Prof. Dr. Radiye Funda KARADENİZ Gaziantep Üniversitesi

UN Peacekeeping operations have been one of the most criticized missions of the United Nations since 1990’s. Blue Helmets’ role in humanitarian crises and civil wars have been widely discussed with reference to their structural limitations as well as their ineffectiveness in finding a workable solution to grave humanitarian crises. Yet, as the numbers of refugees are dramatically increasing in modern warfare, more people (especially women and children) became vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse and other crimes against humanity. The questions of UN peacekeepers’ accountability have always been problematic which further worsens the already problematic legitimacy of UN Peacekeepers in the eyes of the local population as well as global society for their respective missions. This paper attempts to analyze the “accountability” of Blue Helmets through the analyses of Peacekeeping Operation in the Africa region in 2000s and questions the possible judgement option by International Criminal Court (ICC) for their crimes against humanity.

Key Words: Accountability, UN Peacekeeping Operations, Sexual Abuse, ICC

⦁ Introduction

There has been a remarkable progress in terms of legalization in human rights field since the establishemnt of the UN. Especially after the Cold war, increasing number of human rights NGOs and their efforts challenged one of the strongest principles of the UN Charter: state sovereignity. Conceptualized by Katrene Sikking as “Justice Cascade”, in just three decades, state leaders in Latin America, Europe, and Africa have lost their “immunity” from any accountability for their human rights violations, becoming the subjects of highly publicized trials resulting in severe consequences.1 Furthermore, the Responsibility to Protect doctrine showcases a normative shift from “sovereignity as a right” towards “sovereignty as responsibility” for states. The establishment of a permanant court, International Criminal Court (ICC) has been a landmark event in the evolution of human rights norms in world politics. The normative evolution of human rights at the UN and the changing understanding of state sovereignity impose positive obligations on the state, thus promoting an understanding that the state and its rulers can do wrong. On the other hand, the UN has established a system of laws whereby the organization and its agents continue to enjoy “immunity” for crimes committed abroad.2 Although states have lost their immunity from any accountability for their human rights violations in changing world politics, the UN personel continues to enjoy irresponsibility and immunity from accountability, most notably the UN Peacekkepers3. UN’s Status of Forces Aggrement (SOFA) grants absolute immunity to peacekeepers—at least within the United Nations system—for crimes committed abroad. In other words, UN has no jurisdiction to conduct criminal investigations and prosecutions. Criminal investigation and prosecution of UN Peacekeepers are left up to states. Yet, the UN statistics and non-governmental organisation (NGO) reports demonstrate the number of offences committed by peacekeepers including human trafficking, rape and sexual slavery are widespread especially in Africa misions. This legal paradox, if not contradiction, of international human rights law increases the importance of “accountability” question as being one of the main sources of UN’s “illegitimacy” in world politics.

There seems to be an evolution in terms of legalization in human rights field, but the main research question this paper asks; has this resulted in a more legitimate and “humane” governance of the UN in world politics? In other words, although there is

1 Kathryn Sikkink, The Justice Cascade: How Human Rights Prosecutions are Changing World Politics, WW Norton Company, 2011

2 Nadia Abramson, “United Nations Paacekeepers Can Do No Wrong: How Blue Helmets Achieved Immunity for Sexual Abuse in Cote D’Ivore and How to Ensure Accountability in the Future”, Student International Law Papers p: 11. (available at: per.pdf)

3 Mara Pillinger, Ian Hurd, and Michael N. Barnett, “How to Get Away with Cholera: The UN, Haiti, and International Law”, Perspectives on Politics, March 2016, Vol. 14, No.1, p:70.

ample evidence showing an evolutionary trend towards “legalization” on human rights field in the UN platform after the Cold War with respect to states’ and their leaders responsibilities, is there enough evidence supporting a “progress” in terms of a more “humane” governance through the UN? What are the persisting sources of “illegitimacy” of the UN in changing world politics? In light of above questions, this paper attepts to analyze the sources of UN’s illegitimacy with reference to the “accountability” issue of the UN Peacekeepers for their sexual abuses during the African missions by questioning the possible judgement option by International Criminal Court (ICC) for their crimes. This study argues that the “accountability” debade lies at the heart of the discussion of the sources of illegitimacy of the UN in humanitarian governance. Yet, as with the ambigiuites with persecution of peacekeepers in the ICC showcaes, the evolution of “legalization” in human rights field has not, yet, necessarily ends up-or completed- with a genuine “progess” in terms of a more humane global governance through the United Nations.

⦁ Sources of the Illegitimacy of the United Nations: The Accountablity Issue

In democratic countries, citizens delegate power to their governments by electing them as their representatives. By willingly holding them to office, citizens recognize their government’s right to rule.4 However, since power is always delegated for a reason, Grant and Keohane argues, it is legitimate only so long as it serves its original purposes, in the case of the nation, it could be argued the protection of the rights and the pursuit of the public good.5 To be legitimate, governments are not only given the right to rule by their citizens but also held responsible by them.6 Thus, citizens at the national level have a right to “hold their governments to a set of standards”- for instance their promises before elections-to judge whether they have fulfilled their responsibilities in light of these standards and remove them from office if they do not think so in the end. 7 In other words, “people with power ought to be accountable to those who have entrusted them with it.”8

On the other hand, the idea of “accountability” at the international level is much less clear in many aspects. Compared to domestic societies, there is not a world government above states capable of enforcing its rules or laws, judging and punishing immediately if not obeyed. Given the strong voluntary element in rule creation and rule following in the international system, Steffek argues, global governance is even

4 Jean-Marc Coicaud, Legitimacy and Politics, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p: 10

5 Ruth W. Grant and Robert O. Keohane, “Accountability and Abuses of Power in World Politics”,

American Political Science Review, Vol. 99, No. 1 February 2005, p: 32

6 Jean-Marc Coicaud, Legitimacy and Politics, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p: 33

7 Ruth W. Grant and Robert O. Keohane’ ‘Accountability and Abuses of Power in World Politics’

American Political Science Review, Vol. 99, No. 1 February 2005, p: 29

8 Grant and Keohane, p: 32

more dependent on legitimacy beliefs on the part of the ruled over than is any other.9 Furthermore, states remain the most prominent actors in world politics, but it is no longer even a reasonable simplification to think of world politics simply as politics among states. A larger variety of other organizations, from international organizations to multinational corporations as well as nongovernmental organizations exercise authority and engage in political action across state boundaries. As Keohane puts it, in a world of “interdependence without any organized government” or a world constitution, there are multiple audiences and subjects with respect to accountability. Keohane talks about, for instance, transnational accountability, in which demands are largely made by non-state actors and advocacy networks towards states.10 NGO’s and public opinion, Finnemore argues, has become consequential players in generating acceptance or rejection in international legitimacy claims including multilateral ones.11

Thus the identity of the “accountability holders”, at the international level is much more complicated and yet the manner of holding decision makers accountable is less certain.12 Individuals, Steffek argues, are increasingly conceived of as the addressees of international rules and obligations either directly or indirectly.13 Furthermore, as International Organizations grow in power and scope, not only states as actors delegating authority to IOs, but also more populations are becoming increasingly effected and therefore vulnerable to their policies. Concerning organizations like the United Nations, their decisions and missions affect the daily lives of individuals which makes very difficult to exclude them as the addresses of accountability claims. 14 As UN’s decisions intrude more deeply to the daily lives of individuals around the world questions about their accountability and legitimacy necessarily arise.15

In this regard, an important question is whether the UN should be held “accountable” for the violation of the international humanitarian law by forces under its command, namely the peacekeepers. Since Peacekeeping operations have been the main tasks of the UN especially after the Cold War Era, pressure continues to mount, especially from non-state actors, to make UN more “accountable” to domestic populations and

9 Jens Steffek, The Legitimation of International Governance: A Discourse Approach, European Journal of International Relations, 9(2), p: 260

10 Robert O. Keohane, “Global Governanace and Democratic Accountability”,

11 Ian Johnstone, “Legislation and Adjudication in the UN Security Counsel: Bringing Down the Deliberatıve Deficit,” American Society of International Law, p: 277, 2008

12 Andrew Hurrell, ‘Power, Institutions and the Production of Inequality’ Michael Barnett and Raymond Duvall (eds.) Power in Global Governance p: 56-57

13 Jens Steffek, “Legitimacy in International Relations: From State Compliance to Citizen Consensus” (in), Hurrelmann, Schneider and Steffek (eds.) Legitimacy in an Age of Global Politics, Palgrave Macmillian, 2007), P:186

14 Michael Barnett and Martha Finnemore, Rules For the World, Cornell University Press, 2004, p: 171

15 Voeten, “The Political Origins of the UN Security Council’s Ability to Legitimize the Use of Force”, p: 528.

transnational civil societies, as well as to increase access to participatory mechanisms for all affected actors.16 For instance, in 2010, United Nations peacekeepers accidentally brought cholera to Haiti. Nearly a million people were made sick and 8,500 died. Legal activists have sought to hold the UN responsible for the harms it caused and win compensation for the cholera victims. However, these efforts have been obstructed by the structures of public international law—particularly UN immunity—which effectively insulate the organization from accountability.17 Therefore, actors in global civil society increasingly demand setting up “new mechanisms” and norms of introducing accountability of the UN peacekkeping personel.18

⦁ UN Peacekeeping Operations and Immunity from Accountability: The Case of Africa

The “accountability” of peacekeeping personnel for crimes committed on mission is something that the UN has been struggling more with in the last two decades. Peacekeeping operations has been one of the main tasks of the UN, especially after the Cold war era in terms of humanitarian crises management. As of 2015, the United Nations reported a completed fifty-five missions and sixteen currently active missions, covering every region of the world. The approved budget for United Nations peacekeeping operations from July 2014 to June 2015 totaled 7.06 billion U.S. dollars.19 Furtherore, the UN Peacekeping operations has widened in both scope and the definition of the mission. Historically, the original mission of peacekeeping operations was to cool down the conflicts and allow the parties to reach a final peace agreement on their own. Eventually, the mandates became more ambitious, allowing UN peacekeeping staff to hold elections, engage in the peace process, and assist in humanitarian crisis management. In its most extreme form, the United Nations has assumed the role of the government in some states emerging from conflict such as the missions in Cambodia, East Timor, and Kosovo. 20 Yet, most of these UN missions were highly criticized on the ground of being “ineffective” and highly “expensive” ones. For instance, During the cource of Bosnian War, UN Security Council had adopted almost 60 resolutions that mostly deal with the Bosnian peacekeeping force (UNPROFOR) which was the most expensive mission in the history of UN. Security Council veto powers which were unwilling to intervene to the war, issued very big missions to a peacekeeping force- UNPROFOR-which was not compatible with its resources. Ironically, Bosnian war has become both the most expensive misson in its

16 Stewen Bernstein, “Legitimacy in Global Environmental Governance”, Journal of International Law and International Relations, Vol.1, No.1-2, p:142.

17 Mara Pillinger, Ian Hurd, and Michael N. Barnett, “How to Get Away with Cholera: The UN, Haiti, and International Law”, Perspectives on Politics, March 2016, Vol. 14, No.1, p:70.

18 Ibid, p:70.

19 Nadia Abramson ,p:6

20 Ibid, p:6

history and also one of the most criticized ones, especially with its Srebrenitza case in 1995.21

Apart from the important question of “effectiveness” due to structural limitations, UN Peacekkeping operations have been highly criticied on immunity from “accountability” with respect to criminal behaviour by Bluehelmets. Allegations of misconduct amounting to criminal behaviour have increased awareness of the problem of UN “immunity” especially in the last two decades.

In fact, the problem of sexual abuses committed by peacekeepers has been acknowledged by the United Nations (UN) and other international organisations since 1995. However, the Brahimi Report, published in 2000, and which was supposed to provide a comprehensive review of peacekeeping operations, did not address this issue.22 Sexual abuse allegations against peacekeepers and aid workers became an international issue in late 2001 after the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Save the Children conducted a joint study on sexual exploitation of refugee communities in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. The study uncovered allegations of abuse by United Nations peacekeeping forces, international and local nongovernmental organizations, and government agencies. The majority of victims involved were girls between the ages of thirteen and eighteen years old. 23 Following that, the General Assembly passed a resolution 57/306 on 15 April 2003, titled “Investigation into sexual exploitation of refugees by aid workers in West Africa”. Two years later, in 2005 the publication of “Zeid Report” was a turning point in terms of being the first comprehensive analysis of the problem of sexual exploitation and abuse by United Nations peacekeeping personnel.24 In that report, then Secretary-General Kofi Annan clearly underlined the “responsibility” of UN Peacekkeping forces for their sexual exploitation during their mission on Democratic Republic of Congo:

“Sexual exploitation and abuse by a significant number of United Nations peacekeeping personnel in the Democratic Republic of the Congo have done great harm to the name of peacekeeping. Such abhorrent acts are a violation of the

21Oliver Ramsbotham and Tom Woodhouse, Humanitarian Intervention in Contemporary Conflict, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996, p: 186. One should note here, the history of UN peacekeeping operations were not always full of failures. In 1998, United Nations peacekeeping forces were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their valuable contributions as observers and negotiators in war-torn regions. See Abramson, p:11.

22 Marco Odello and Róisín Burke, “Between immunity and impunity: peacekeeping and sexual abuses and violence”, The International Journal of Human Rights, 2016, p: 1.

23 Abramson, p:4

24 UN General Assembly Document, 24 March 2005 A/59/710 (available at

fundamental duty of care that all United Nations peacekeeping personnel owe to the local population that they are sent to serve. 25 (emphasis edded)

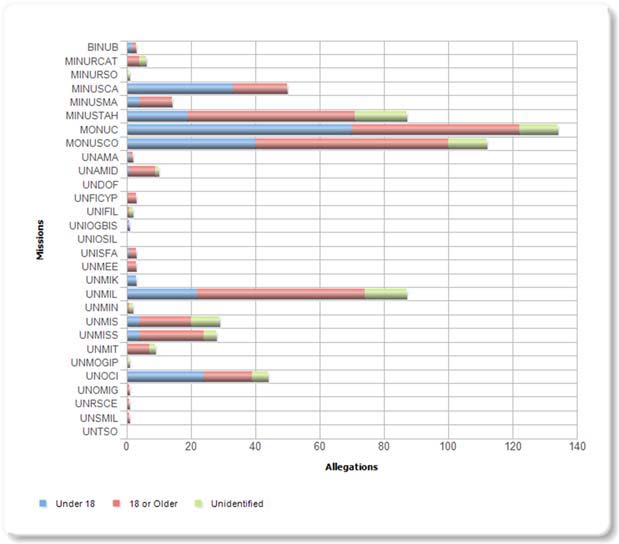

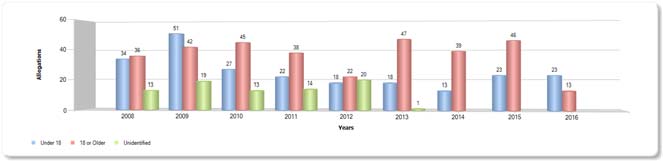

Since the publication of the Zeid Report in 2005, the UN has adopted a series of documents and some initiatives have been taken, mainly with administrative and disciplinary consequences for personnel considered responsible of sexual abuses.26 In this regard, a Conduct and Discipline Unit (CDU) was established at UN Headquarters in 2005 to provide oversight on conduct and discipline issues in peacekeeping operations and special political missions. Yet, there is still little clarity on the outcomes of the procedures set up by the UN and by states, showing that they do not yet act properly to address this phenomenon.27 Furthermore, new allegations of sexual misconduct surfaced in the Africa region with the work of NGOs in the last couple of years.28 Most recently, new allegations of sexual misconduct were report by a Human Rights Watch on Central African Republic.29 The UN statistics with regard to sexual exploitation and abuse allegations per missions and per years are shown in the following two tables .

25 Ibid

26 See UN Conduct and Discipline Unit (available at

27 Odello and Burke, p: 2.

28 See Melanie O’Brien, “Protectors on trial? Prosecuting peacekeepers for war crimes and crimes against humanity in the International Criminal Court”, ARC Centre of Excellence in Policing and Security, Griffith University (available at

29 See https://www.hrw.org/africa/central-african-republic

Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Allegations Per Mission Involving Minors

Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Allegations Per Year Involving Minors

The table clearly illustrates that almost all of the allegations are on missions in the Africa region. (UNMIL, UNOCI, UNMISS, MONUC, MONUSCO) In fact, Africa has been a giant laboratory for UN peacekeeping and has repeatedly tested the capacity and political resolve of an often dysfunctional 15-member UN Security

Council.30 Several NGO Reports indicate that this is only the surface of the giant iceberg. Reports also emphasize that of the cases referred to states, few states respond to the referrals, and those that do rarely result in disciplinary action. Not all states have the legislative means to prosecute, and not all states take action to prosecute criminal conduct by their peacekeepers. It is also unclear from the UN reports what disciplinary action is taken, including whether or not prosecutions are held for criminal conduct. Confirmed cases of prosecution include the Canadian cases prosecuting nine defendants for torture and murder of a Somalian teenager; and the US case of Ronghi, found guilty of raping and murdering a ten-year-old girl in Kosovo.31 The UN has no standing army or police force available; consequently, it depends on the contributions of member states which may voluntarily contribute personnel for operations around the globe for accomplishing these broad missions.32

More importantly, the UN still has no jurisdiction to conduct criminal investigations and prosecutions. Criminal investigation and prosecution is left up to states. The United Nations has two permanent sources of law and one case-specific negotiation tool to exercise its “immunity privileges” in peacekeeping operations. These are the United Nations Charter, the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations, and Status of Forces Agreements (SOFAs), respectively. According to Status of Forces Aggrement (SOFA) aggrement, if the host government believes that a foreign military member of the peacekeeping operation committed a criminal offense, the accused will be subject “to the exclusive jurisdiction of their respective participating states.” This language grants absolute immunity to peacekeepers—at least within the United Nations system—for crimes committed abroad. In fact, these immunities are codified as being necessary for the independent exercise of their functions in connection with the organization. However, paradoxically, these immunities challenge the very legitimacy of UN peacekeeping as producing immunity from criminal accountibiliy33.

In sum, there ise considerable progress in human rights law with respect to the accountability of “states” on their violation of human rights. However, this is not true

30 Adekeye Adebajo and Chris Landsberg, “Back to the future: UN peacekeeping in Africa”, International Peacekeeping, 7:4, 2000, pp: 161-188, p:161-162

31 Melanie O’Brien, “Protectors on trial? Prosecuting peacekeepers for war crimes and crimes against humanity in the International Criminal Court”, ARC Centre of Excellence in Policing and Security, Griffith University (available at

32 Abramson,p:6

33 In 1989, the General Assembly requested the Secretary-General to prepare a “model status-of-forces agreement for peace-keeping operations,” which the Secretary-General presented one year later. At the very beginning of the document, Article II of the Model SOFA states that the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities applies to United Nations peacekeeping operations. Further, the document includes a provision on jurisdiction, which states, “All members of the United Nations peace-keeping operation including recruited personnel shall be immune from legal process in respect of words spoken or written and all acts performed by them in their official capacity.” See Abramson, p: 20

for the world organization. State’s “sovereign immunity” norm is challenged with the advance of human rights norms and the establishment of International Criminal Court is one of the most influencial developments in human rights. The question is could this also be applied to Blue Helmets for their crimes commited abroad to overcome this accountability-immunity paradox which has increasingly become a real challenge to UN’s legitimacy and actorness in world politics?

⦁ Accountability of Blue Helmets: Prosecution Through International Criminal Court

ICC has juristiction over 4 types of crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and aggression. However the abuses that the peacekeepers instigated do not seem to escalate to the level of either genocide, or crimes against humanity, as the Rome Statute, the authorizing treaty of the ICC, defines them.34 Firstly, it is difficult to imagine peacekeepers being actively involved in perpetrating genocidal acts, let alone being ascribed this type of special intention.35 The greatest difficulty in determining a crime by a peacekeeper to constitute a crime against humanity, on the other hand, lies in the fact that crimes by peacekeeping personnel ‘tend to be isolated and sporadic acts of military indiscipline or indifference’, rather than part of a widespread or systematic attack. A crime against humanity must be committed as part of the widespread or systematic attack. Furthermore, the aggressor’s act of murder, etc, must be pursuant to a “policy”. It is the existence of this policy that donates the criminal act with the character of a crime against humanity and excludes isolated acts of murder and so on from the court’s jurisdiction.36 Thus allegations against peacekeepers typically would not involve attacks against civilian populations involving such a widespread and systematic quality. A crime committed by a peacekeeper would most probably be considered an isolated incident and therefore would not amount to a crime against humanity.37

As yet, the recent accounts of UN peacekeepers’ involvement in ‘sex trafficking’ and ‘child prostitution rings’ in the Africa region suggests that not all criminal acts of these soldiers are isolated, personal events. If peacekkepers’ acts are proved to be a part of a consistent pattern of offences by a number of persons, he or she may be properly charged with crimes against humanity.38 The majority of peacekeeping personnel would not be aware of the details of a plan or policy of a widespread or systematic

34 Notar, Susan A. “Peacekeepers as Perpetrators: Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Women and Children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.” American University Journal of Gender, Social Policy and the Law. 14, no. 2 (2006): 413-429, p:426.

35 Max Du Plesis and Stephen Pete, “Who Guards the Guardians: The ICC and serious crimes committed by United Nations peacekeepers in Africa”, African Security Review 13(4), 2004, p: 10.

36 Ibid, p:10.

37 Notar, p:413-429.

38 Plesis and Pete, p:11.

attack. Still it is something that those in superior positions within the mission may well be aware of, given their role in interacting directly with any leaders or commanders of parties to the conflict. The involvement of multiple peacekeeping personnel systematically in the sexual exploitation of the local population might be charged with crimes against humanity. 39

With regards to war crimes, Under Article 8(1) of the Rome Statute there is no absolute requirement that a war crime be committed on a large-scale. Article 8(1) states that the ‘Court shall have jurisdiction in respect of war crimes in particular when committed as part of a plan or policy or as part of a large-scale commission of such crimes’. Therefore a single occurrence of a war crime is sufficient for the ICC to establish jurisdiction. A war crime avoids any similar requirement like being “systematic”, and thus it will be far more likely that a crime by a peacekeeper is classified as a war crime. The argument here is that, peace support operations are located in places experiencing on-going conflict, or in a post-conflict situation. Their very presence is related to the armed conflict. A crime such as sexual exploitation takes advantage of the situation created by the fighting, as the conflict has created a society in which women and children are vulnerable and open to abuse. Thus, it can be argued that these crimes are committed in the context of an armed conflict, and are associated with an armed conflict, even if hostilities have ceased. Crimes committed by peacekeeping personnel may fall within this “expansive” interpretation. 40

On the other hand, it may be the case that the Court finds that the crime(s) in question do not have a direct link to armed conflict because it was committed after the cessation of hostilities, after the conclusion of peace, and thus might conclude that there is no jurisdiction under Statu of Rome, Article 8. Furthermore, there is no clear legal stance on the issue of peacekeeping personnel involvement in armed conflict, and whether and when they are considered to be “combatants” engaging in armed conflict or “civilians”. Thus, with regards to war crimes, the determination of the existence of an armed conflict and the status of such a conflict are the two biggest challenges.41 Ultimately, however, it would not be impossible to prosecute a peacekeeper under Article 8 of the Rome Statute. Once the existence of an armed conflict has been established, applying the broad interpretation of association with armed conflict established by the ICTY in the Foca case will enable the Prosecutor to argue that crimes committed by a peacekeeper are committed in the context of and are associated with an armed conflict, regardless of whether or not the peacekeeping personnel were engaged as combatants in that armed conflict. Another complication would be whether a peacekeeper’s crime can be linked to the attack or armed conflict. 42

39 Ibid

40 O’Brien, p: 12-25

41 Fort the details of the legal issue, see O’Brein p: 12-25.

42 Ibid.

According to Plesis and Pete, if it can be shown that a peacekeeper committed a war crime (such as murder, torture, or rape) as part of a large-scale commission of such a crime, that peacekeeper may be guilty of a war crime without any need to prove the special intention that would be required for genocide and crimes against h ICC may have a role to play, but this role is strictly limited by the nature of the crimes over which this court exercises jurisdiction, and by the doctrine of complementarity which restricts the jurisdiction of the court to a great extent. Prosecutions of peacekeepers will most likely to continue to be conducted largely by the national state of the peacekeeper concerned, and prosecutions of such soldiers by the ICC will remain a very distant exception to that norm. 43 Yet, as this paper tries to showcases, the allegations are very rare which further increases the pressure towards UN system on accountability and increasingly became one of the crutial sources of its illegitimacy in World Politics.

⦁ In Guise of Conclusion: Evolution without Progress?

UN’s legitimacy is the main source of its authority and power in world politics. To be powerful, it must be seen to serve some legitimate purpose- like preserving international peace and security, promoting human rights. More importantly, it must be perceveid to serve this “purpose” in an impartial, neutral and technocratic way, by using impersonal rules.44 As individuals are increasingly becoming the adresees of UN’s legitimacy claims, their beliefs about the legitimacy of the UN matters. As yet, there is ample evidence of harms caused by UN peacekeeping to people it is to serve. The United Nations has recently found itself accused of various kinds of harms, including exploiting weak and vulnerable people. Peacekeepers have repeatedly been accused of criminal activity and human rights violations, including trafficking, child abuse, and rape, and the UN has apparently been covering up this misbehavior, most recently in the Central African Republic. In many cases, rather than accepting responsibility the UN has relied on the law of immunity as a shield against accountability.45

Although there exists an undeniable “progress” in terms of legalization in human rights field with respect to states-since their leaders are not immune from human rights abuses and could be held accountable through many ways including International Criminal Court; this progress seems not to be true for the UN. In contrast, the law of immunity has increasingly become a barrier towards the advancement of human rights in which UN is to serve in its Charter as exemplified by the immunity from accountability for sexual abuse of the UN Peaceekers in the Africa Region. There is

43 Plesis and Pete, p: 12-15.

44 Michael Barnett and Martha Finnemore, Rules for the World,Cornell University Press, 2004, p: 20-21

45 See Mara Pillinger, Ian Hurd, and Michael N. Barnett, “How to Get Away with Cholera: The UN, Haiti, and International Law”, Perspectives on Politics, March 2016, Vol. 14, No.1.

increasing pressure from civil society institutions to make UN more accountable to the people it is to serve. In sum, legalization is thought to serve “human beings” by limiting the ambitions and power struggles of states in world politics. The evolution in human rights field is the evindence of this, as yet the resistence of the UN for changing its structure and working methods is standing on the way towards that “progress”. This denotes to a legitimacy crises of the UN.

References

Abramson, Nadia, “United Nations Paacekeepers Can Do No Wrong: How Blue Helmets Achieved Immunity for Sexual Abuse in Cote D’Ivore and How to Ensure Accountability in the Future”, Student International Law Papers p: 11. (available at: uments/abramson.paper.pdf)

Adebajo, Adekeye and Chris Landsberg, “Back to the future: UN peacekeeping in Africa”, International Peacekeeping, 7:4, 2000, pp: 161-188, p:161-162

Barnett, Michael and Martha Finnemore, Rules for the World,Cornell University Press, 2004, p: 20-21

Bernstein, Stewen, “Legitimacy in Global Environmental Governance”, Journal of International Law and International Relations, Vol.1, No.1-2, p:142.

Coicaud, Jean-Marc, Legitimacy and Politics, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p: 10.

Grant, Ruth W. and Robert O. Keohane, “Accountability and Abuses of Power in World Politics”, American Political Science Review, Vol. 99, No. 1 February 2005, p: 32

Hurrell, Andrew, ‘Power, Institutions and the Production of Inequality’ Michael Barnett and Raymond Duvall (eds.) Power in Global Governance p: 56-57.

Johnstone, Ian, “Legislation and Adjudication in the UN Security Counsel: Bringing Down the Deliberatıve Deficit,” American Society of International Law, p: 277, 2008.

Michael Barnett and Martha Finnemore, Rules For the World, Cornell University Press, 2004, p: 171.

Notar, Susan A. “Peacekeepers as Perpetrators: Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Women and Children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.” American University Journal of Gender, Social Policy and the Law. 14, no. 2 (2006): 413-429, p:426.

O’Brien, Melanie, “Protectors on trial? Prosecuting peacekeepers for war crimes and crimes against humanity in the International Criminal Court”, ARC Centre of Excellence in Policing and Security, Griffith University (available at

quence=1)

Odello, Marco and Róisín Burke, “Between immunity and impunity: peacekeeping and sexual abuses and violence”, The International Journal of Human Rights, 2016, p: 1.

Pillinger Mara, Ian Hurd, and Michael N. Barnett, “How to Get Away with Cholera: The UN, Haiti, and International Law”, Perspectives on Politics, March 2016, Vol. 14, No.1, p:70.

Plesis, Max Du and Stephen Pete, “Who Guards the Guardians: The ICC and serious crimes committed by United Nations peacekeepers in Africa”, African Security Review 13(4), 2004, p: 10.

Ramsbotham, Oliver and Tom Woodhouse, Humanitarian Intervention in Contemporary Conflict, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996, p: 186.

Sikkink, Kathryn, The Justice Cascade: How Human Rights Prosecutions are Changing World Politics, WW Norton Company, 2011.

Steffek, Jens, The Legitimation of International Governance: A Discourse Approach, European Journal of International Relations, 9(2), p: 260.

Steffek, Jens, “Legitimacy in International Relations: From State Compliance to Citizen Consensus” (in), Hurrelmann, Schneider and Steffek (eds.) Legitimacy in an Age of Global Politics, Palgrave Macmillian, 2007, p:186.

Voeten, Eric “The Political Origins of the UN Security Council’s Ability to Legitimize the Use of Force”, p: 528.

UN Conduct and Discipline Unit (available at

UN General Assembly Document, 24 March 2005 A/59/710 (available at

https://www.hrw.org/africa/central-african-republic