Turkey’s future

Flags, veils and sharia

Jul 17th 2008 | ANKARA, KARS AND TOKAT

From The Economist print edition

Behind the court case against Turkey’s ruling party lies an existential question: how Islamist has the country become?

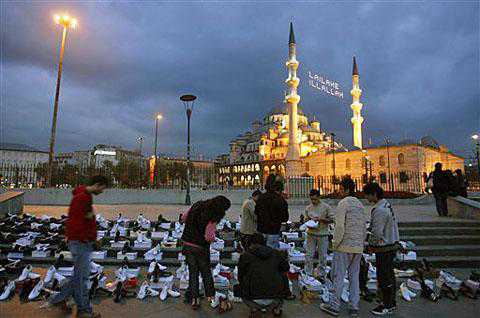

EPA

A MARBLE fountain held up by bare-breasted maidens in the eastern city of Kars is a source of pride for the city’s mayor, Naif Alibeyoglu. Yet last November the sculpture vanished a few days before a planned visit to Kars by Turkey’s prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Fearful of incurring the wrath of Mr Erdogan and his mildly Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP), the mayor (himself an AKP man) reportedly arranged for its removal.

In the event, the prime minister never arrived—and the fountain came back. The incident may be testimony to the prudery of Mr Erdogan, and of the AKP more broadly. But could it also be evidence of their desire to steer Turkey towards sharia law? The country’s chief prosecutor, Abdurrahman Yalcinkaya, might say so. In March he petitioned the constitutional court to ban the AKP and to bar Mr Erdogan and 70 other named AKP officials, including the president, Abdullah Gul, from politics, on the ground that they are covertly seeking to establish an Islamist theocracy.

Turkey has been in upheaval ever since. After hearings earlier this month, a verdict is expected soon, maybe in early August. Most observers expect it to go against the AKP. Turkey has banned no fewer than 24 parties in the past 50 years, including the AKP’s two forerunners. In 23 of these cases, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the bans violated its charter.

Yet Mr Yalcinkaya’s indictment lacks hard evidence to show that the AKP is working to reverse secular rule. Much of his case rests on the words, not the actions, of Mr Erdogan and his lieutenants. Among Mr Erdogan’s listed “crimes” is his opinion that “Turkey as a modern Muslim nation can serve as an example for the harmony of civilisations.” That is hardly a call for jihad. The AKP has promoted Islamic values, but it has never attempted to pass laws inspired by the Koran.

None of this seems to impress Turkey’s meddlesome generals, who are widely believed to be the driving force behind the “judicial coup” against the AKP. This follows the “e-coup” they threatened last year by issuing a warning on the internet against making Mr Gul president. Some renegade generals are also involved in the so-called Ergenekon group; 86 members were charged this week with plotting a coup (see article).

The generals and their allies believe that nothing less than the future of Ataturk’s secular republic is at stake. Similar rumblings were heard when the now defunct pro-Islamic Welfare party first came to power in 1996. It was ejected a year later in a bloodless “velvet coup” and banned on similar charges to those now levelled at the AKP. But with each intervention the Islamists come back stronger.

Unlike their pro-secular rivals, Islamists have been able to reinvent themselves to appeal to a growing base of voters. Nobody has done this more successfully than Mr Erdogan with the AKP. An Islamic cleric by training, Mr Erdogan became Istanbul’s mayor when Welfare won a municipal election in 1994. He was booted out in 1997, and jailed briefly a year later for reciting a nationalist poem in public that was deemed to incite “religious hatred”.

It was a turning-point. Mr Erdogan defected from Welfare with fellow moderates to found the AKP in 2001. He and his friends said that they no longer believed in mixing religion with politics and that Turkish membership of the European Union was the AKP’s chief goal. And when the AKP won the general election of November 2002, it formed a single-party government that did something unusual for Turkey: it kept its word.

The death penalty was abolished; the army’s powers were trimmed; women were given more rights than at any time since Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the secular Turkish state, made both sexes equal before the law. Despite Mr Erdogan’s calls for women to have “at least three children”, abortion remains legal and easy. This silent revolution eventually shamed the EU into opening formal membership talks with Turkey in 2005, an achievement that had eluded all the AKP’s predecessors in government.

The government’s economic record was impressive, too. The economy bounced back from its nadir in 2001, growing by a steady average annual rate of 6% or more. Inflation was tamed (though it has crept back up recently). Above all, foreign direct investment, previously paltry, hit record levels. For a while, Turkey seemed to have become a stable and prosperous sort of place. That is surely why 47% of voters backed the AKP in July 2007, a big jump from only 34% in 2002.

Many see the campaign to topple the AKP as part of a long battle pitting an old guard, used to monopolising wealth and power, against a rising class of pious Anatolians symbolised by the AKP. Others say it is mostly about an army that believes soldiers, not elected politicians, should have the final say over how the country is run.

Yet the real struggle “is between Islam and modernity”, says Ismail Kara, a respected Islamic theologian. Adapting to the modern world without compromising their religious values is a dilemma that has long vexed Muslims. For Turkey the challenge is also to craft an identity that can embrace all its citizens, whether devout Muslims, hard-core secularists, Alevis or Kurds. If the generals had their way, everyone would be happy to call himself a Turk, all would refrain from public displays of piety and nobody would ever challenge their authority. But the Kemalist straitjacket no longer fits the modern country. Opinion polls suggest that most Turks now identify themselves primarily as Muslims, not as Turks. The AKP did not create this mindset: rather, it was born from it.

The caliph of Istanbul

Islam has been intertwined with Turkishness ever since the Ottoman Sultan adopted the title of “Caliph”, or spiritual leader, of the world’s Muslims almost six centuries ago. When Ataturk abolished the caliphate in 1924 and launched his secular revolution, he did not efface piety; he drove it underground. Turkey’s brand of secularism is not about separating religion from the state, as in France. It is about subordinating religion to the state. This is done through the diyanet, the state-run body that appoints imams to Turkey’s 77,000 mosques and tells them what to preach, even sometimes writing their sermons.

In the early days of Ataturk’s republic, the façade of modernity was propped up by zealous Kemalists, who fanned out on civilising missions across Anatolia. They would drink wine and dance the Charleston at officers’ clubs in places like Kars. “My grandmother, she told me about the balls, the beautiful dresses. Kars was such a modern place then,” sighs Arzu Orhankazi, a feminist activist. In truth, life outside the cities continued much as before: deeply traditional and desperately poor.

A big reason why Anatolia seemed less Islamist in the old days is because it was home to a large and vibrant community of Christians. But this demographic balance was brutally overturned by the mass killings and expulsions of Armenians and Greeks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Take Tokat, a leafy northern Anatolian town where Armenians made up nearly a third of the population before 1915. The only trace that remains of a once thriving Armenian community is a derelict cemetery overgrown with weeds and desecrated by treasure-hunting locals.

Much of this history is overlooked by the secular elite. Pressed for evidence of creeping Islamisation under the AKP, they point to the growing number of women who wear the headscarf, which is proscribed as a symbol of Islamic militancy in state-run institutions and schools. Mr Erdogan’s attempt to lift the ban for universities, which was later overturned by the constitutional court, is a big part of Mr Yalcinkaya’s case against him and the AKP.

Yet surveys suggest that, except for a small group of militant pro-secularists, most Turks do not oppose Islamic headgear, least of all in universities. Its proliferation probably has little to do with Islamist fervour, but is linked to the influx of rural Anatolians into towns and cities. The exodus from the countryside accelerated under Turgut Ozal, a former prime minister who liberalised the economy in the early 1980s. For conservative families, covering their daughters’ heads became a way of protecting them in a new and alien world.

Once urbanisation is complete the headscarf will begin to fade, says Faruk Birtek, a sociologist at Istanbul’s Bogazici University. Bogazici was always refreshingly unbothered by students with headscarves. But the rules were tightened in the 1990s. And around the time the constitutional court in June overturned the new AKP law to let women with headscarves attend university, Bogazici’s liberal female director was squeezed out.

Like many, Summeye Kavuncu, a sociology student at Bogazici, has been caught in the net. She complains that her stomach “gets all knotty each time I go to university. I no longer know whether to keep my scarf on or to take it off. The secularists look upon us as cockroaches, backward creatures who blot their landscape.” Few would guess that Ms Kavuncu belongs to a band of pious activists who dare to speak up for gays and transvestites.

Social and class snobbery may partly drive the secularists’ contempt for their pious peers. But it is ignorance that drives their fear. Bridging these worlds can be tricky, “because Islam is not like other religions, it’s a 24-hour lifestyle,” comments Yilmaz Ensaroglu, an Islamic intellectual. “Devout Muslims pray five times a day.”

Wine, women and schools

The biggest fault-lines in Turkey’s sharpening secular/religious divide concern alcohol, women and education. When Welfare rose to power in the 1990s, one of its first acts was to ban booze in restaurants run by municipalities under its control. Party officials argued that pious citizens had the right to affordable leisure space that did not offend their values. Some AKP mayors have pushed this line further. They want to exile drinkers to “red zones” outside their cities. A newly prosperous class of devout Muslims is creating its own gated communities, and a growing number of hotels boast segregated beaches and no liquor. A survey shows that the number of such retreats has quadrupled under the AKP. Taha Erdem, a respected pollster, says the number of women wearing the turban, the least revealing headscarf of all, has quadrupled too.

All this is feeding secularist paranoia about creeping Islam. Are these fears justified? In the big cities conservative Anatolians are expanding their living space. But this is not at the secularists’ expense. Life for urban middle-class Turks, and certainly for the rich, continues much as before. It is in rural backwaters that freewheeling Turks fall prey to what Serif Mardin, a respected sociologist, calls “neighbourhood pressure”. For instance, Tarsus, a sleepy eastern Mediterranean town (and birthplace of St Paul), made headlines recently when two teenage girls were attacked by syringe-wielding assailants who sprayed their legs with an acid-like substance because their skirts were “too short”.

Habits in the workplace are changing too. Female school teachers have been reprimanded for wearing short-sleeved blouses. During the Ramadan fast last year the governor’s office in Kars stopped serving tea for a while. Secular Turks contend that Islam will inevitably wrest more space from their lives and must be reined in now. With no credible opposition in sight, many look to the army as secularism’s last defender.

So do many of Turkey’s estimated 15m Alevis, who practise an idiosyncratic form of Islam: they do not pray in mosques, they are not teetotal and their women do not cover their heads. The government has not kept its promise formally to recognise Alevi houses of worship, called cemevler. Nor has it heeded Alevi demands for their children to be exempted from compulsory religious-education classes that are dominated by Sunni Islam. “There is a systematic campaign to brainwash us, to make us Sunnis,” complains Muharrem Erkan, an Alevi activist in Tokat.

The battle for Turkey’s soul is being waged most fiercely in the country’s schools. Egitim-Sen, a leftist teachers’ union, charges that Islam has been permeating textbooks under the AKP. Darwin’s theory of evolution is being whittled away and creationism is seeping in. Islamist fraternities, or tarikat, continue to ensnare students by offering free accommodation. The quid pro quo is that they fast and pray, and girls cover their heads.

Yet the biggest boost to religious education came from the army itself, after it seized power for the third time in 1980. Communism was the enemy at the time, so the generals encouraged Islam as an antidote. Religious teaching became mandatory. Islamic clerical-training schools, known as imam hatip, mushroomed.

Another example of how army meddling goes awry is Hizbullah, Turkey’s deadliest home-grown Islamic terrorist outfit. Hizbullah (no relation to its Lebanese namesake) is alleged to have been encouraged by rogue security forces in the late 1980s to fight separatist PKK rebels in the Kurdish south-east. The group spiralled out of control until police raids in 2001 knocked it out of action. But not entirely. Former Hizbullah militants are said to have regrouped in cells linked to al-Qaeda, and took part in the 2003 bombings of Jewish and British targets in Istanbul.

Banning the AKP could strengthen the hand of such extremists, who share the fierce secularists’ belief that Islam and democracy cannot co-exist. If instead the AKP stayed in power, that would bring Islamists closer to the mainstream. “Six years in government has tempered even the most radical AKP members,” comments Mr Ensaroglu. True enough. AKP members of parliament wear Zegna suits and happily shake women’s hands; their wives get nose jobs and watch football matches; their children are more likely to study English than the Koran.

Had Mr Erdogan made an effort to reach out to secular Turks, “we might not be where we are today,” concedes a senior AKP official. He missed several chances. The first came last autumn when the AKP was trying to patch together a new constitution to replace the one written by the generals in the 1980s. Mr Erdogan never bothered to consult his secular opponents. He ignored them again when passing his law to let girls wear headscarves at universities. Critics say that his big election win turned his head. “Erdogan accepts no advice and no criticism,” whispers an AKP deputy. “He’s become a tyrant.”

Maybe he has. But that does not mean he deserves to be barred from politics, and his party banned.