Suna Erdem in Istanbul

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the Turkish Prime Minister, prayed with thousands of mourners yesterday at the funeral of victims of Sunday’s bomb attack in Istanbul. He called for a united response to the threat of terror and dismissed concerns over the possibility of his ruling party being closed down by a court ruling.

“Today is a day for unity and togetherness. The more support we can give each other and the more we can give terrorism the cold shoulder, the more successful we will be as a nation,” said a sombre Mr Erdogan.

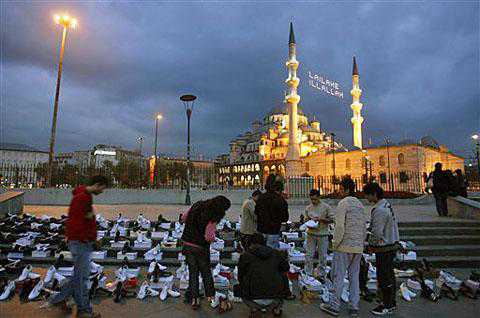

He was speaking after carrying a flag-draped coffin and embracing mourners at a mosque in the Gungoren district of Istanbul. The funeral was held for 10 of the 17 victims killed there on Sunday night. More than 150 people were injured.

Turkey was shocked by the ferocity of the double bombing, which came at a time of political turmoil. On Friday charges were brought against 86 alleged ultra-nationalists for an anti-Government campaign of murder, terror and civil unrest.

Yesterday the country’s Constitutional Court began deliberating a controversial case to shut down Mr Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AK) over accusations of pro-Islamic activities.

Nobody has claimed responsibility for Sunday’s attack — a small bomb apparently designed to lure a crowd, followed by a larger one intended to cause maximum casualties. Initial reports pointed to the secessionist Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), but the group, which usually hits rural military targets, has denied responsibility and condemned the attackers.

Mr Erdogan angrily denied rumours that he had cancelled a nearby appointment due two hours before the explosions. Because of the timing of the bombings there is speculation that the Ergenekon group was involved. It is a shadowy ultra-nationalist entity which, according to Friday’s charge sheet, is active within the security forces, the judiciary, business, politics and media.

“The atmosphere in Turkey is very tense,” said Deniz Ulke Aribogan, rector of Bahcesehir University. “The PKK could have done this . . . but to be honest it does not fit in with the PKK’s general strategy. This could even turn out to have links with Ergenekon.”

The court case against the ruling party and the Ergenekon investigation go to the heart of the struggle between Turkey’s secularist elite — which includes the judiciary, the politically powerful military and the bureaucracy — and the Government of Mr Erdogan, a political Islamist turned EU advocate whose supporters range from devout Muslims to free-market liberals and socialists.

Critics of the court case against the AK party say that it is more of a power struggle between Turkey’s Establishment and the new guard rather than a classic secularist-Islamist showdown. They argue that the decision by the constitutional court, expected within days, will determine whether Turkish democracy has matured after decades of party closures, military coups and assassinations.

“The closure case is indefensible both in terms of democracy and the law,” said Hasan Cemal, a veteran liberal commentator who writes for the mainstream Milliyet newspaper. “We can only hope that the High Court is aware of this and will reach a historic decision that could be the turning point of Turkish democracy.”

Seven of the 11 members of the court, seen as a bastion of Turkey’s secularist Establishment, must vote in favour for AK to be closed.

They could also ban Mr Erdogan, President Gül and 69 other AK members from party politics for five years.

If the party is banned, its rump could re-form under another name and the banned members could run as independents. In theory a legal loophole would allow Mr Erdogan to win a seat as an independent and continue to control the Government.

But while the damage could be minimal for AK — which believes that it will still be the biggest party, particularly if it appeals for the sympathy vote — an outright ban could jeopardise Turkey’s newly resurgent economy, its strong ties with the West, its European Union membership talks and its recent role as Middle East mediator.

Party insiders expect a compromise verdict — which would keep AK open but deprive it of Treasury funding. This would amount to a slap on the wrist for the Government.

The evidence against AK in the 161-case indictment has been derided as flimsy, and is based largely on reported comments and a parliamentary vote to loosen restrictions on university education for women wearing the Muslim headscarf. That vote — also supported by a nationalist party that has escaped censure — has been overturned by the Constitutional Court.