By Gareth Jenkins

Tuesday, August 5, 2008

Basbug’s appointment followed a three-day meeting of the Supreme Military Council (YAS), which meets at the beginning of August each year to decide on the annual round of promotions and postings in the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK). Basbug has been replaced as Land Forces Commander by General Isik Kosaner, the head of the Gendarmerie. The commanders of the Turkish Navy, Admiral Muzaffer Metin Atac, and the Turkish Air Force, General Aydogan Babaoglu, remain unchanged.

Although there is nothing in military regulations to prevent a chief of the TGS from being drawn from the Navy or Air Force, the post has always been filled by a member of the Land Forces, usually the Land Forces commander. The Gendarmerie is distinct from the Land Forces in terms of personnel, with only rare transfers of officers between the two. However, it has traditionally been commanded by a four star general on secondment from the Land Forces. Kosaner is a career Land Forces officer and has been replaced as commander of the Gendarmerie by General Atilla Isik, the current chief of staff of the Land Forces.

In terms of postings, the military year runs for 12 months from the end of August. Chiefs of the TGS can serve for a maximum of four years, provided that they do not reach the compulsory retirement age of 67; in which case they are obliged to step down at the end of the following August.

Basbug was born in 1943 and is expected to serve as chief of the TGS until 2010. It currently appears that he will be succeeded by Kosaner, who was born in 1945 and could thus serve as chief of staff until the end of August 2012. The commands of the individual services have a lower retirement age of 65.

Basbug has a reputation for combining a formidable intellect with an unswerving commitment to the ideological legacy of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk (1881-1938), the fierce secularist who founded the modern Turkish Republic in 1923. In the months leading up to the YAS meeting, hard-line elements in the Islamist media launched a defamation campaign against Basbug in the hope of preventing him from being appointed chief of the TGS. In theory at least, it would have been possible for Gul to delay ratifying Basbug’s appointment, thus forcing him to retire at the end of August while still head of the Land Forces; but Gul appears to have had no hesitation in ratifying Basbug’s appointment when it was presented to him for his approval on August 4.

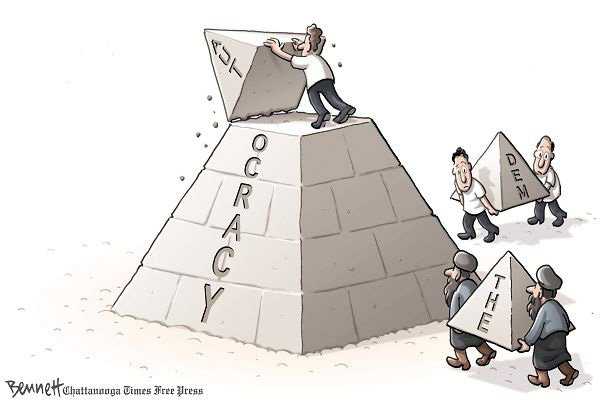

More surprising than what happened at the YAS meeting was what did not happen. Traditionally, the TGS has used the August YAS meetings and, to a lesser extent, a second YAS meeting in December each year, to purge the officer corps of anyone deemed to be ideologically suspect.

Like most of its counterparts around the world, the Turkish military has its own court system to try those alleged to have breached laws and regulations. The military courts follow standard judicial procedures, including hearings, the presentation of evidence, prosecution and defense. In contrast, the meetings of the YAS are closed. The members of the council simply vote on cases brought before them. The accused do not have the right of defense. In many instances, they are only aware of the allegations against them when they are notified after the YAS meeting that they have been expelled from the military. There is no right of appeal.

Although it has also been applied for other offences, the system has been the main instrument used against suspected Islamist activists. The TGS has long suspected, and not without justification, that Islamist groups are trying to infiltrate the ranks of what is regarded as one of the bastions of the Turkish secular establishment. YAS meetings have proved a convenient way of purging the officer corps of those believed to have been recruited by Islamist groups, without the need to present evidence in a court or risk the possibility of an acquittal. It is also likely, however, that some of the officers expelled over the years for alleged Islamist activism have been guilty of nothing more insidious than increased piety.

The number of officers expelled has tended to vary. At the YAS meeting in August 2007, a total of 23 officers were expelled, 10 of them for alleged Islamist activism. This year, however, for the first time in 16 years, there were no expulsions (Milliyet, Vatan, Hurriyet, Milliyet, Radikal, August 5).

In a country already awash with conspiracy theories, the absence of any expulsions has sent the rumor mills into overdrive. The pro-AKP press has triumphantly speculated that Basbug must have agreed not to expel any officers for Islamist activism in return for Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan promising to ensure that the continuing Ergenekon investigation (see EDM, July 29) would not implicate any members of the military high command (Zaman, Yeni Safak, Sabah, August 4). This is unlikely in the extreme.

In the prevailing political climate in Turkey, no incoming chief of the TGS, much less one as ruthlessly ideologically committed as Basbug, could afford to be seen to be bowing to pressure from the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) over what most secularists regard as a politically motivated investigation.

It is difficult to imagine that, since the last YAS meeting, there have been no perceived serious breaches of military discipline similar to those previously dealt with at these meetings. Rather than allowing suspected Islamist activists to remain within its ranks indefinitely, it is more likely that the TGS is either biding its time or will opt to deal with them through more conventional disciplinary procedures.