Hugh Eakin

A woodcut of the Süleymaniye mosque in Istanbul by Melchior Lorichs, 1570

In March 1548, having brought the Ottoman Empire to the height of its power, Suleiman the Magnificent decided to build a mosque in Istanbul. “At that time,” an anonymous chronicler explains,

His Highness the world-ruling sultan realized the impermanence of the base world and the necessity to leave behind a monument so as to be commemorated till the end of time….Following the devout path of former sultans, he ordered the construction of a matchless mosque complex for his own noble self.

In late May of this year, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan—Turkey’s powerful prime minister, a devout Muslim, and the self-styled leader of the new Middle East—announced that he would be erecting his own grand mosque above the Bosphorus. It will be more prominent than Suleiman’s. The chosen site—the Büyük Çamlıca Tepesi, or Big Çamlıca Hill, overlooking the city’s Asian shore—is 268 meters above sea level; it is easily the most conspicuous point of land in greater metropolitan Istanbul. (A favorite look-out spot, it is here that the protagonist in Namik Kemal’s late Ottoman novel Awakening (1876) begins a tragic love affair with a woman of loose morals.)

“We will build an even larger dome than our ancestors made,” an architect involved in the project, Hacı Mehmet Güner, boasted to the Turkish daily Milliyet in early July. Güner added that the mosque would be built in a “classical style” and have six minarets—more than any in Istanbul save for the Blue Mosque (Suleiman’s mosque, the Süleymaniye, has four). He also said that their height would exceed that of the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, whose tallest minarets are 344 feet.

Among Turkey’s secular elite, these plans have met with a mixture of incredulity and derision. Suleiman’s mosque complex was built by Sinan, the greatest Ottoman architect; Güner was a little known municipal public works official. One architecture professor likened the envisioned vast prayer hall to an “Olympic stadium.” Nor has Erdoğan’s previous record of mosque building helped his case. In July, with debate over the Çamlıca project in full swing, the prime minister announced the completion of another Ottoman-style mosque on Istanbul’s Asian shore by calling it a selatin mosque—using the word for religious institutions built at the behest of a sultan. “Has Erdoğan Just Declared His Sultanate?,” one Turkish newspaper editor asked.

AP Photo/Thanassis Stavrakis

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan campaigning in front of a mosque in Istanbul, June 11, 2011

Nonetheless, walking the streets of Istanbul this summer, I found it difficult to miss the intended symbolism. Erdoğan, who comes from the city’s rough Kasımpaşa neighborhood and has not conquered any foreign countries, is hardly a Suleiman. But after a decade in power in which he has presided over a record economic boom and a dramatic resurgence of Turkey in international affairs, he is widely acknowledged as the most powerful politician since Kemal Atatürk, the country’s modern founder. At the same time, he has gone further than any of his predecessors in moving away from the stridently anti-religious state that Atatürk created in the 1920s.

Soon after proclaiming the new republic in 1923, Atatürk’s government abolished the caliphate and closed the madrasas, turning Turkey overnight into the most secular nation in the Muslim world. But earlier this year, Erdoğan declared he wanted the country to have a “religious youth,” and, since March, when parliament passed a controversial bill to expand Islamic education, more than sixty new religious schools have opened in Istanbul. When you enter the courtyard of one of the city’s historic mosques, you are increasingly likely to run into groups of young boys or girls (they are separated by gender) sitting at little desks, receiving instruction in the Quran.

Headscarves, once rare in the fashionable European districts that Orhan Pamuk writes about in The Museum of Innocence, have become common, including in high-end, designer versions. All over the city, Ottoman religious complexes are being restored at great expense (among them a beautiful Sinan madrasa, built around an octagonal courtyard, which construction workers proudly showed off to me). One Turkish political analyst complained that the call to prayer, broadcast everywhere on outdoor speakers, is far louder than it used to be. And the Ramadan fast, once better known locally for being honored in the breach, was embraced this summer with newfound rigor. Under pressure from the religious establishment, a local rock music festival that was staged a few days before the beginning of the Muslim holiday decided to ban alcohol, despite having been sponsored by Turkey’s largest beer company.

This is not the first time that Turkey’s deeply secular state has seemed to move in a more religious direction. As far back as 1967, a close replica of another sixteenth-century Sinan mosque was built in Ankara; a more daring, modernist design by Vedat Dalokay was rejected. Turgut Özal, who was prime minister in the late 1980s and is credited with beginning the economic opening to the world that has matured under Erdoğan, was a devout Muslim who went on the Hajj while in office. And Erdoğan’s own AKP party is a direct heir to the since-banned Islamist party of Necmettin Erbakan, who briefly served as Turkey’s first Islamist prime minister in the 1990s (leading to a military coup in 1997).

But what makes the recent changes particularly dramatic is that the Turks themselves seem to be generally embracing them: headgear has become a point of pride for many Anatolian businesswomen, and the recent alcohol bans appear to have been imposed as much by local communities—by some far more than others—as by higher authorities. Indeed, Erdoğan, now in his third term of office, has a huge base of popular support. And while the AKP has not quite gained the supermajority in parliament the prime minister has sought, it has had sufficient dominance to transform significant parts of the Turkish political system.

In successive steps that have continued in recent days, the prime minister has skillfully taken control of the once-dominant—and fiercely secular—Turkish military; dozens of top generals and admirals have been thrown in jail for alleged coup plots, including one that supposedly involved bombing mosques in Istanbul. Meanwhile, his conservative Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi or AKP) has been pushing through far-reaching reforms of the judiciary and the education system, some suggest, to favor its own agenda. (Erdoğan’s rapid transformation of the courts from a bastion of Turkey’s military-secular elite into a key part of his own campaign against the military can only be the envy of Egypt’s new Islamist president, Mohammed Morsi, whose judiciary remains loyal to its own politically powerful armed forces.) More radically, AKP leaders are now drafting a new constitution that, if adopted, could turn Turkey’s parliamentary system into a strong presidential republic—just in time for Erdoğan’s planned move in 2014 to the presidency, where he could spend another decade running the country.

Certainly, the most controversial aspects of Erdoğan’s leadership have little to do with religion. Human rights activists are far more concerned by what they describe as his increasingly authoritarian style of leadership and his use of the police and judiciary to suppress critics. In July, the government announced it was eliminating the much-criticized special court system that has been used to prosecute “conspiracy” cases and “terrorism-related” crimes. But dozens of journalists, students, and scholars are already in jail, many of them for writing about the Kurdish PKK, or criticizing the government’s ties to the powerful Gulen religious movement. Abolishing these courts has struck critics as largely cosmetic; other courts may end up with the same sweeping powers. In a recent interview with Christiane Amanpour, Erdoğan disputed the number of jailed journalists, claiming that “there are 80 people who are in prison right now. Only nine of them have yellow press identification cards.” But he also said, “insult is one thing; criticism is another thing. I will never put up with an insult.”

At the same time, the Turkish government has gone from a dull but reliable NATO ally to an assertive leader of the new Middle East. Before last year’s uprisings, Turkey made much of its “zero problems” strategy with all neighboring powers—a policy that included promoting economic ties with Assad’s Syria and Ahmadinejad’s Iran, and, before the flotilla raid, working relations with Israel. Now, Ankara has renewed ties with Hamas while aggressively supporting the Sunni-led Syrian uprising and giving refuge to fugitive Iraqi vice president Tariq al-Hashemi, a Sunni leader who was sentenced to death in Iraq last week on charges of orchestrating sectarian killings. With Sunni-led governments in charge through much of the Middle East and Turkish economic growth driven increasingly by trade relations with the Gulf, Erdoğan seems to have found it convenient to bring Turkey closer to the old lands of the Caliphate, regardless of the diplomatic consequences.

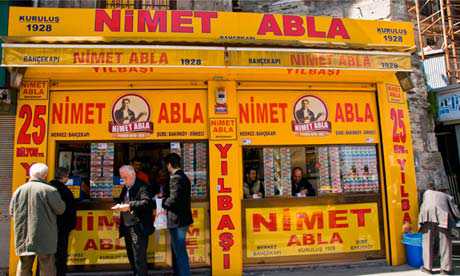

All this, too, can be seen on the streets of Istanbul. Amid the attractions of the Old City, the usual summer influx of European tourists was leavened this year by groups of visitors from the Arabian peninsula, often with the women in full black niqab. In fact, there has been a staggering 71 percent increase in Arab visitors to Turkey in the first six months of 2012, a figure that is even higher for some nations like the UAE and Qatar. I asked several Turkish friends about it and was told that Arabs have supplanted Israelis, who before the flotilla incident used to visit Turkey in large numbers. Part of the appeal—along with Halal food, Turkish soap operas, and ample new shopping centers—seems to be that the country is now led by a popular Muslim leader with strong pro-Arab credentials. A new Turkish law has also made it easier for foreign nationals to invest in real estate, a move that seems to be particularly aimed at Arab investors.

One longtime Istanbul resident, citing the government’s interest in malls and infrastructure projects that can “rival Mecca,” suggested that the new pro-Arab policies have been accompanied by Persian Gulf-style urban development. Large as it is, she observed, the planned Çamlıca mosque complex—which is apparently to be funded by pro-AKP businessmen—is far from Erdoğan’s most ambitious building project. In recent months, he has renewed his campaign promise to dig a second Bosphorus, a thirty-mile shipping channel to the Black Sea—an undertaking so enormous that, he claims, it would surpass the Suez and Panama canals. And the government’s announcement this spring that it plans to fill in a 2.8 square mile section of the Sea of Marmara along the Istanbul shore—apparently to create a public assembly space for up to 800,000 people—has been compared by one writer to “wanting to straighten the Seine or turn the Colosseum into a football stadium.”

Vedat Dalokay

Vedat Dalokay’s experimental 1957 design for the Kocatepe Mosque in Ankara, later rejected in favor of a replica of a Sinan mosque in Istanbul

But far more than the scale or apparent religious content of such mega-projects, what has rankled Turkish critics most is how they will look. In late July, perhaps embarrassed by the Çamlıca controversy, the Islamic association overseeing the mosque project took out advertisements in Turkish newspapers announcing an architectural design competition for the complex. But the hasty competition seemed to foreclose the possibility that something exciting or unusual might arise from it: entries were limited to Turkish architects and not much more than a month was allotted for designs to be submitted—all of which had to conform to the enormous proportions of the building specified. (The winning design was supposed to be announced earlier this month, but the decision has been postponed.)

The larger irony is that in calling for a huge new mosque in the tradition of Sinan, Erdoğan may be missing the more fundamental lesson of the Ottoman architect’s work. As Bruno Taut, the German architect who emigrated to Turkey to flee the Nazis, argued, Sinan was himself a proto-modernist whose ability to create extraordinary beauty from novel engineering had more in common with twentieth-century German functionalism than earlier Islamic architecture. Rather than imitating his predecessors’ designs, he continuously sought out new and more subtle ways to surpass them. Sinan aimed to be more elegant than his Byzantine and Ottoman forebears; Erdoğan, it seems, just wants to be taller.