The author of “The Innocence of Objects” and “Silent House” believes all American presidents should read “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.”

What book is on your night stand now?

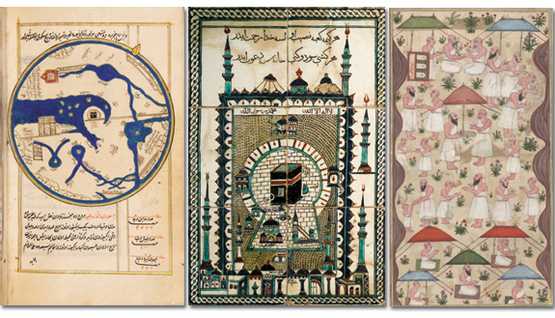

Ferdowsi’s “Shahnameh” — subtitled “The Persian Book of Kings,” a great translation and compilation by Dick Davis — is a Penguin Classics edition. Like Rumi’s “Masnavi,” or “Arabian Nights,” “Shahnameh” is a great ocean of stories that I browse from time to time in various Turkish and English translations to be inspired by or to adapt an ancient story as I did in “My Name Is Red” and “The Black Book.” At the heart of this epic lies the great warrior Sohrab’s search for his father, Rostam, who without knowing that Sohrab is his son, kills him in a fight.

The place of this great tragic story in the Persian-Ottoman-Mughal literary canon is very similar to the place of the legend of Oedipus in the Western canon, but the story still awaits its inventive Freud to address the similarities and radical differences. Comparative literature can teach us more about East-West than the rhetoric of the “clash of civilizations.”

What’s the last truly great book you read?

The truly great books are always novels: “Anna Karenina,” “The Brothers Karamazov,” “The Magic Mountain.”. . . Just as with “Shahnameh,” I browse these books from time to time to remember how a great book works on us, or to teach my students at Columbia University.

And what’s the worst book you’ve ever read?

The worst books are also bad novels. Just as good books give me the joys of being alive, bad novels depress me and as I notice this sentiment coming from the pages, I stop. I also do not hesitate to walk out of a movie house if the film is bad. Life is short, and we should respect every moment of it.

Any guilty reading pleasures — book, periodical, online?

For a long time I naïvely believed that thrillers and detective novels were a waste of time. And I thought that was why I felt guilty enjoying the novels of Patricia Highsmith. Later I realized that the guilt comes not from reading thrillers but from her ingenious method of making the reader identify with the murderer. She is a great Dostoyevskian crime writer. I also wish I had read more of John Le Carré. I feel guilty if I read too much book-chat on the Internet.

The last book that made you laugh?

Oscar Wilde always makes me smile — with respect and admiration. His short stories prove that it is possible to be both sarcastic, even cynical, but deeply compassionate. Just seeing the cover of one of Wilde’s books in a bookshop makes me smile. Julian Barnes has some of his cruel and humane humor. I liked Barnes’s “The Sense of an Ending” very much.

The last book that made you furious?

Adam Hochschild’s “King Leopold’s Ghost” is about the atrocities committed by the army and people of King Leopold II of Belgium, between 1885 and 1908, with the pretext of “fighting against slavery” but actually simply to make money in the Congo. Leopold’s men killed more or less 10 million people in Africa. We all know too well that the rhetoric of “civilization, modernization” is a good excuse to kill, but this great book was too infuriating for anyone — especially someone like me who believes in the idea of Europe too much.

If you could recommend one book to the American president, what would it be? To the prime minister of Turkey?

Many years before he was elected president, I knew Obama as the author of “Dreams From My Father,” a very good book. To him or to any American president, I would like to recommend a book that I sometimes give as a gift to friends, hoping they read it and ask me, “Why this book, Orhan?” “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values” is a great American book based on the vastness of America and the individual search for values and meaning in life. This highly romantic book is not a novel, but does something every serious novel should do, and does it better than many great novels: making philosophy out of the little details of daily life.

I respected the Turkish prime minister’s politics of pushing the army away from politics and back to the barracks, though I am not happy about going to courts for my political opinions like many, many others during his reign. He sued a cartoonist for picturing him as a cat, though as anyone who comes here knows we all love cats in Istanbul. I am sure Erdogan would enjoy the great Japanese writer Natsume Soseki’s book “I Am a Cat,” a satirical novel about the devilish dangers of too much Westernization, narrated by a smart cat.

You have been charged with “insulting Turkishness” for acknowledging the mass killings of Kurds and Armenians, and have been outspoken about Turkey’s bid to join the European Union. In these instances, were you acting as an engaged citizen or do you think writers have a responsibility for social activism?

At most I was acting as an engaged citizen. I do not have systematical political beliefs, nor am I a self-consciously political writer. Yet my books are political because my characters live in troubled times of political unrest and cultural change. I like to show my readers that my characters do make choices all the time, and that is political in a literary way in my fiction.

I am never motivated by political ideas. I am interested in human situations and funny stories. The political problems I face in Turkey are not because of my novels but because of the international interviews I make. Whatever I say outside of Turkey is twisted, changed a bit back at home to make me look silly and more political than I am.

Once I complained to the young Paul Auster — a writer I admire, whom I met in Oslo as he was also doing interviews, like me, to promote one of his books — saying that they are asking me political questions all the time, and that it may be easier to be an American writer. He said they are also asking him about the gulf war all the time. This was the first gulf war! In the 20 years that passed in between, I perhaps learned that political questions are a sort of destiny for literary writers, especially if you come from the non-Western world.

The best way to avoid them is to be political — like a diplomat — and answer only the literary questions. But my character is not the character of a successful diplomat. I lose my temper and answer some of the political questions and either end up in court or face a campaign by right-wing newspapers in Turkey. Novels are political not because writers carry party cards — some do, I do not — but because good fiction is about identifying with and understanding people who are not necessarily like us. By nature all good novels are political because identifying with the other is political. At the heart of the “art of the novel” lies the human capacity to see the world through others’ eyes. Compassion is the greatest strength of the novelist.

You can bring three books to a desert island. Which do you choose?

Encyclopaedia Britannica’s 1911 edition, the first edition of “Encyclopaedia of Islam” (1913-1936) and Resat Ekrem Kocu’s “Encyclopedia of Istanbul” (1958-1971), which I wrote about in my book “Istanbul,” will keep me busy for 10 years. My imagination works best with facts — especially if they are a bit dated. After 10 years they should pick me up from the desert island to publish the novels I wrote there.

You’ve lived on and off in America. Which American writers do you especially admire? Any who have influenced your work?

The late John Updike once wrote that all third world writers are influenced by Faulkner. I am one of them. Faulkner showed us that our subject matter may be provincial, away from the centers of the West and politically troubled, yet one can write about it in a very personal and inventive way and be read all over the world.

I’ve read almost all of Faulkner and Hemingway and Fitzgerald. I also read all of Updike’s literary reviews he wrote for The New Yorker. I learned a lot from Updike and benefited from his reviews of my books too. Since I went to an American secular high school in Istanbul, Robert College, I’ve read “Tom Sawyer” as required reading, as well as “A Separate Peace” and “To Kill a Mockingbird,” enjoying the democratic and egalitarian spirit of these books. Salinger was not taught at school then, so I read “The Catcher in the Rye” as a subversive book in high school years. I admire the novels of Thomas Pynchon, the intelligence of Nicholson Baker. I respect Dave Eggers. . . .

But when someone asks me about American literature, I immediately think of Hawthorne, Melville and Poe. For me these three writers represent more than anyone else the American spirit. Perhaps because it is easy for me to identify with their anxiety of provincialism and wild imagination, their small number of readers in their time and their energy and optimism, their successes and spectacular failures. In my imagination I associate Poe, Melville and Hawthorne with some mystery just as I associate, say, German Romantic painters and their landscapes with something unknowable.

How has your training as a painter informed the way you write and read your books?

As I wrote in my autobiographical book “Istanbul,” and now in “The Innocence of Objects,” I was raised to be a painter. But when I was 23-years-old, one mysterious screw got loose in my head and I switched to writing novels.

I still enjoy the pleasures of painting. I am a happier person when I paint, but I feel that I am engaged more deeply with the world when I write. Yes, painting and literature are “sister arts” and I taught a class about it at Columbia. I liked to ask my students to close their eyes, entertain a thought and to open their eyes and try to clarify whether it was a word or an image. Correct answer: Both! Novels address both our verbal (Dostoyevsky) and visual (Proust, Nabokov) imaginations. There are so many unforgettable scenes in the novels of Dostoyevsky, but we rarely remember the background, the landscape or the objects in the scenes.

There are also other types of novelists who compose memorable scenes by forming pictures and images in our minds. Before Flaubert’s “perfect word,” there should be a perfect picture in the writer’s imagination. A good reader should occasionally close the novel in her hand and look at the ceiling and clarify in her imagination the writer’s initial picture that triggered the sentence or the paragraph. We writers should write for this kind of imaginative reader. Over the years, the painter in me taught essentially five things to the writer in me:

1)

Don’t start to write before you have a strong sense of the whole composition, unless you are writing a lyrical text or a poem.

2)

Don’t search for perfection and symmetry — it will kill the life in the work.

3)

Obey the rules of point of view and perspective and see the world through your characters’ eyes — but it is permissible to break this rule with inventiveness.

4)

Like van Gogh or the neo-Expressionist painters, show your brushstrokes! The reader will enjoy observing the making of the novel if it is made a minor part of the story.

5)

Try to identify the accidental beauty where neither the mind conceived of nor the hand intended any. The writer in me and the painter in me are getting to be friendlier every day. That’s why I am now planning novels with pictures and picture books with texts and stories.

The city of Istanbul has changed enormously in the last 50 years. How has this change been reflected in literature?

The previous generation of Turkish writers were more busy with life and social injustice in rural Anatolia while my poor Istanbul of the 1950s grew from one million to 14 million in my lifetime. The suburban neighborhoods, small fishermen’s villages, fancy summer resorts for the Westernized upper classes and the factories and working-class quarters that I describe in “Silent House,” along with their angry young men, the nationalists, the fundamentalists and the secularists and their political problems are part of the big metropolis now. I feel so lucky to have observed all this immense, amazing growth from the inside. And since most of it happened in the last 15 years, it is hard to catch up with it too. As I did in the years that I wrote “Silent House,” I still take long walks in the various quarters of the city, as it gets bigger and bigger, enjoying everything I see, observing the high-rises that replace old shantytowns, the fancy malls built on old summer cinema gardens, all sorts of new shops and local fast-food chains representing many communities and endless crowds in the streets.

A collection of the articles presented at the first international conference of Linguistic Ties between Iran and Turkey has been published in Iran.

A collection of the articles presented at the first international conference of Linguistic Ties between Iran and Turkey has been published in Iran.