The Fall And Rise Of Turkey At Eurovision

Posted by John Kennedy O’Connor on Dec 20th, 2012 in Articles | 1 comment

In the last week, TRT have announced they are withdrawing Turkey from the 2013 Eurovision Song Contest. The nation that once struggled at Eurovision until televoting and diaspora kicked in have decided enough is enough, and are criticising some of the core rules of the Song Contest in the 21st century.

Can their arguments be justified, or is Turkey simply taking their ball away and not letting anyone else play? John Kennedy O’Connor looks at the rise and fall of Turkey at Eurovision.

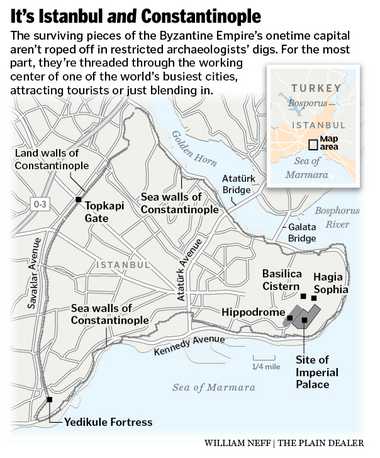

So farewell then Turkey.“We’ve had enough”, yes that is your catchphrase. Unless there is a miracle, the 2014 Eurovision Song Contest will not be staged in Istanbul, Ankara, or indeed anywhere on Turkish soil. The Turks have taken their key changes away and have withdrawn from Eurovision 2013, following in the steps of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Portugal and Slovakia.

The latter three countries have never won the contest, nor indeed made any real impact on the scoreboard at all, so their absence probably lessens the blow to the contest line-up. Indeed, the Slovaks haven’t been seen in the Saturday night show since 1998, when they placed 21st. Over 48 years the Portuguese have always had a very dubious relationship with the Eurovision voters, never having placed in the top five at all, the only country from the pre-expansion of 1993 to suffer that ignominy. And if it wasn’t for Hari Mata Hari’s 3rd place in 2006 there wouldn’t be much for the fans to remember about Bosnia & Herzegovina either.

Magdalena Tul, Poland 2011 (Photo: Pieter Van Den Berghe (EBU))

Many people have added Poland to the list of withdrawing countries as well, even though they are technically continuing their AWOL run from 2012. Their impressive debut in 1994 (scoring a splendid 2nd place) has never been matched and only one further top ten finish ever occurred for them, with seven of their last eight entries failing to qualify.

If we’re including Poland, then we can’t forget previous entrants Monaco, Morocco, Andorra, Luxembourg and the Czech Republic, who are all staying away from Malmö in May. Luxembourg and Monaco are sorely missed in some quarters, both having triumphed in the Contest back in the days when it was largely a Western European event. Six wins between them is the same as the ex-Soviet Union and Yugoslav bloc can boast combined. Yet by the time those two departed the competition, neither was enjoying particularly good results. Monaco’s return was short lived when they failed to progress beyond the semi-final stage.

It may smack of bad sportsmanship, but you can understand really why these countries have given up the ghost.

But not so Turkey.

From Zero To Hero, Every Way That They Can

Like Portugal, the Turks had a very dodgy start to their Eurovision story, finishing last upon their debut in 1975. Certainly, with only Israel and Yugoslavia for company amongst countries outside the traditional Western and Nordic European geography, all three countries entries seemed at odds with the music being submitted by everyone else.

Turkey had another problem… their mutually antagonistic relationship with the Greeks next door. Greece got a one year start on the Turks in the contest and withdrew when Turkey entered the following year. The Turks did the same in 1976 when Greece opted for a Cypriot singer singing (or some might say wailing) an impassioned plea for her homeland, so recently occupied by the Turkish army. It wasn’t until 1978 that the two countries felt comfortable enough to share the Eurovision stage and despite the odd withdrawal on both sides for varying reasons, the two settled down to be familiar Eurovision nations over the coming decades; despite neither nation finding much appreciation for their efforts.

Then the voting system began to shift away from the reliance on national juries. Turkey found they were to be one of the biggest surprise beneficiaries of the embryonic tele-voting instigated in 1997. Prior to this year, the Turks had grazed the top 10 only once, when in 1986 they found themselves at a high of 9th out of the 20 songs. Otherwise, their track record was grim. 17 entries on the bottom half of the scoreboard, including three last places, two with no points at all.

All that changed in 1997 when to the astonishment of most, including the Turks themselves, they soared up the scoreboard to finish 3rd, with four countries awarding their song ‘Dinle’ douze points! Remarkable, particularly when considering that their previous eighteen entries had amassed just three 12 points between them! Turkey’s new found popularity was something of a blip, but there was clear evidence that a rosier, nay, more golden, Eurovision future lay ahead. Five countries tele-voted in 1997 and all had the Turks on their score sheet; the Germans putting them at the very top for the very first time.

Despite this excellent result (perhaps made even more remarkable as the Turkish entry was performed in the cursed second place in the running order), it didn’t immediately spark a particularly great new future for the continually failing Eurovision nation. The next couple of years didn’t bring top ten finishes, but they did bring a regular ‘douze points’ from the tele-voters of Germany. A nation with a very high population of Turkish expats, it was clear that a sense of national pride was prevailing and the German votes were being heavily influenced by this loyalty.

Things began to get better again for the Turks from 2000 when they started experimenting with English songs. Now it wasn’t just the expats in Germany, but those in the Netherlands and France who were willing to show their support year in, year out. Despite a couple of slip backs, it seemed that with heavy diaspora support through tele-voting, Turkey were finally getting the knack of the Contest and this proved the case when at last they took gold in the 2003 contest in Riga, with the belly-dancing Sertab Erener squeaking home in 1st place, bringing the contest to Istanbul and putting a Eurovision Song Contest trophy on the TRT Executive’s shelf.

From that moment on, there really was no looking back. Although another victory has so far eluded the Turks, generally speaking, they’ve had one of the most consistent records of any country since the turn of the century. Indeed, since winning in 2003, only three of their entries have failed to place in the top seven in the final. Pretty remarkable for a country that had such an arid period of failure for so very long. But all of a sudden, TRT appear to have fallen out of love with the contest they had become to be so apparently good at. Why?

Failing To Live It Up

According to the press release issued by the station, the Turkish TV executives are unhappy with both the current voting structure (50% jury/50% tele-voting) and that the Big Five nations (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom) are given automatic places in the Saturday night Grand Final. Both are reasonable arguments that have been raised by many fans. But are they reasonable for the Turks?

Yuksek Sadakat, Turkey 2011 (Pieter Van Den Berghe (EBU))

Prior to 1993, every country that wanted to enter could do so, simply by complying with the EBU rulebook. From 1993 until 1999, every country was vulnerable to qualification procedures, based largely on their previous results. Since 2000, this has not applied to any of the Big Five. So what? What impact has this had on Turkey? In this period, the Turks have only once failed to qualify for the final of the Eurovision Song Contest. That was in 2011 in Düsseldorf, when they placed 13th in their semi-final.

But was this failure now due to the imposition of the 50/50 voting split that had served them so well in 2010? Clearly, not. In Oslo, the Turks had done very nicely; their second best finish, ever in fact. Even if there hadn’t been a 50/50 split in the 2011 semi-final, neither the jury nor the tele-voters put the Turks in their top ten, so regardless of which method was used, they wouldn’t have qualified. Both sets of judges simply didn’t rate the song and lest we forget, it is a Song Contest after all.

Love Me Back?

Since the Big Five nations don’t participate in the semi-finals, but they do vote, they can hardly be blamed for the failure of Turkey’s 2011 entry either. Do the Turks perhaps think that had they not had to qualify at all, their result in the 2011 Final would have been better? Hard to imagine based on the 13th place out of the 19 entries in their semi that an automatic qualification would have produced something particularly special from Yuksek Sadakat (who were an internal selection). But being in the final directly, even if you ultimately finished last, is a big difference than being knocked out in the semi.

Does the Big Five rule create an unfair advantage for those who enjoy that status, particularly to the detriment to those that don’t? Apparently not. Since their win in 2003, only when Germany won the contest convincingly in 2010, have Turkey ever been bettered in the final by one of the Big Five, with Italy scoring 2nd the following year when the Turks were relegated.

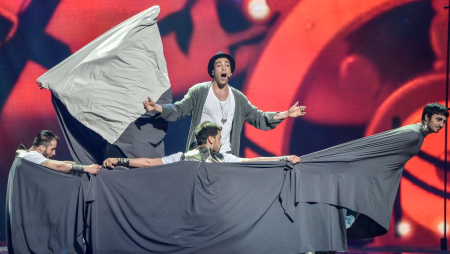

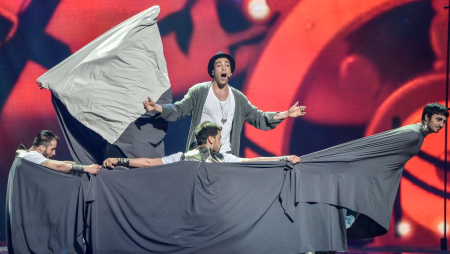

Man-boat, Man-boat, you have made a Man-Boat! (Andres Putting (EBU))

Maybe that’s the point. Since being given automatic passage, the record of the Big Five isn’t particularly impressive. The point could be argued therefore that since they aren’t generally coming up with songs that are deemed of particularly high quality by those judging them (the viewers or the jury) that putting them straight through to the final is unfair on countries that are only narrowly missing out on a place in the final. That’s a strong argument indeed. If you take certain examples (‘Even If‘ in 2008 and ‘Love Will Set You Free‘ in 2012, both for the United Kingdom), it’s impossible to imagine some of the Big Five entries coming through a semi-final in a million years, based on their low scores achieved in the Grand Final.

But without the Big Five’s viewing figures on the Saturday night attracting sponsors, without their entry fee offsetting that cost for the smaller countries taking part, and without their presence legitimising the Contest, there would be no Eurovision Song Contest. Indeed there would be no EBU. Twenty songs are still given the chance to compete in the Eurovision final every year, the same number generally speaking that has competed each Saturday night since the late 1970’s. It’s a tricky argument with fair play on one side and economic reality on the other.

Shake It Up?

Qualification began in 1993. Twenty Contests have now been held under a number of qualification systems. Thirteen of them have been staged with the ‘big’ nations removed from the procedure. Turkey failed to qualify twice: Once with the Big Five (then the Big Four) also having to navigate qualification, in 1994 under a questionable system that wasn’t revealed until after their 1993 result was deemed insufficient; and once more in 2011 as discussed. It isn’t at all clear that the Big Five rule has impacted Turkey in any way shape or form. If they’re implying that the Big Five songs simply aren’t good enough and should be tested in qualification, then that’s a reasonable argument indeed and one that I am sure many other nations ponder. Certainly the fans and viewers do. If this is the reason Turkey have left, it’s not an argument that’s easily refuted.

There can be no Ley with no Rimi Rimi, but can there be Eurovision without Turkey? It would seem so. Can there be a Eurovision without the Big Five? I would suggest not. Yes, it survived 1982 when neither France nor Italy turned up, but perhaps the saving grace came from the global mega-hit that won that year. Did anyone really notice that Germany weren’t there in 1996 or that Italy was missing in action over an extended period? I did, but who can say if the wider audience cared?

Kenan Doğulu Shaking It Up, Turkey 2007

Turkey has benefitted from the introduction of tele-voting more than most. You only have to compare their record prior to 1997 and since to pick up on that. Arguably, you could also point to the expansion of the Contest as having been favourable to the Turkish entries. The arrival of their ex-Soviet neighbours did certainly help their fortunes. Could it be that switching to English made all the difference? Or that their entries just got better? Who knows? Whatever the reason, Turkey has been one of the most consistently high scoring nations over the past decade. It’s a shame they are now leaving, just as it’s a shame when any country leaves the contest.

Turkey’s Withdrawal Is A Loss To The Contest

I’m all in favour of a smaller Eurovision final. Writing as a fan, I really dislike that the final has become so huge. When it first increased to 22, then 23, then 25 nations, I was thrilled; but not anymore. It should shrink. Alas, I can’t put forward any meaningful way of doing this; at least not one that would likely gain universal acceptance and besides, nobody has asked me. Nations withdrawing is not the answer; particularly as this diminishes the semi-finals, not the final itself.

Personally, I won’t miss Turkey at Eurovision. I know I’m generally out-of-step with the masses of fans who seem to adore the Turkish entries, but their entries have always left me cold; or indeed, sometimes quite hot under the collar. I’ve sat with gaping jaw and bulging eyes on many occasions as Turkish entries I’ve truly despised have rocketed up the final scoreboard, punching way above their weight, largely in my mind anyway, thanks to their reliance on their tele-voting diaspora. There, I’ve written it. 2003, 2004, 2008 and 2010 particularly spring to mind as results that left me silenced. However, I fully accept that music (perhaps more so ‘Eurovision’ music) is totally subjective and one man’s Après Toi is another man’s Diggi-Loo, Diggi-Ley. I always bow to the result.

TRT have taken the decision to withdraw from the Eurovision Song Contest, but the reasons given simply don’t add up. They won’t be in Malmo and that diminishes the Contest as a whole; as indeed does the absence of Luxembourg, Monaco, Poland, Portugal and every other nation not taking part. I hope they come back soon, but for now it’s farewell and the end of this Eurovision chapter for Turkey.

Source :