In a 2003 TV commercial for Cola Turka, the actor Chevy Chase was seen speaking Turkish and then sporting a moustache, after taking just one sip of the intended challenger of Coke in this country. This sensational ad – which riffed on the old theme of American cultural imperialism through its number-one agent, Coca-Cola – was the first time that Turkish soft drinks caught our attention. Though we didn’t take to the overly sweet Cola Turka, we did start looking beyond, to its local brethren in the market: gazoz, a world of nearly extinct Turkish carbonated drink brands with a fanatical following.

One recent winter morning at Avam Kahvesi, the waiter, Ulaş, pitched wood into a large fireplace in the back. The dance of flames refracted through gazoz bottles that lined the walls, sat on tables, and peaked out from crates stacked around the room. There were literally gazoz bottles everywhere in this one-of-a-kind shrine to Turkish soft drinks.

“Think of it like wine,” said Ulaş. “Each town has its own climate and water. That all goes into a bottle of gazoz.” Ulaş opened a bottle of Zafer brand gazoz for us. Along with the promised essence of Denizli, an inland city in southern Turkey where the drink is made, there was a tinny flavor of strawberry that coated the mouth, much like biting into a Chewels. “That’s the best-loved gazoz,” Ulaş said. We sipped it through a straw as he showed us a jacks-like game played with gazoz caps. We didn’t quite catch the rules but Ulaş assured us that the player with bigger hands almost always wins.

In a swath of streets not far from Taksim Square, where the kebab shops all look the same and student-oriented cafés serving Nescafé and çay have opened one after the other, Avam Kahvesi opened two years ago with a radical concept: to be the first Turkish specialty café serving as wide a variety as possible of the legendary Anatolian soft drinks that were once the only carbonated option but are now little more than sweet, bubbly reminders of a Turkey long gone. As Ulaş puts it, “We did this because gazoz is not popular. But gazozcu folks do come and support us.” (“Gazozcu” means those who love gazoz.)

Avam Kahvesi’s owner, Barış Aydın, came of age in the 1980s drinking the now-defunct Elvan Gazozu, and even experimented with homemade gazoz back then. He believes drinking gazoz is a statement against cultural imperialism, a “provokasyon.” The menu at Avam, which boasts 14 different kinds of gazoz, includes notes on the flavor, origin and history of each producer in Turkish and English. Aroma Meltem Gazozu, for example, was big in the 1970s and is featured in Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence. Barış admits that there are some flavors of gazoz that he doesn’t even like, but he says they all “taste of nostalgia.”

The first time we actually drank one of these carbonated drinks was at the suggestion of a burly masseur in a hamam (Turkish bath), who indicated with a thumb to his moustache that we might need one after the trouncing we’d just received. How could we refuse? Its restorative powers aside, gazoz undoubtedly carries with it the heavy weight of times gone by. Gamze Eskinazi, a glassblower who melts down old Uludağ gazoz bottles into artistic objects, told us, “In this technological era, objects that touch the heart are important. Like the texture of an Uludağ bottle, for example.”

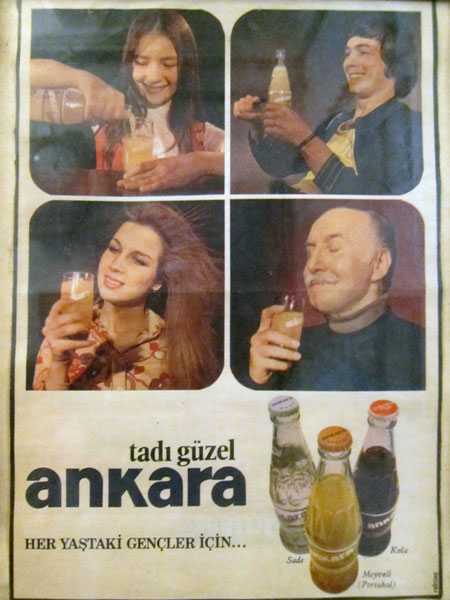

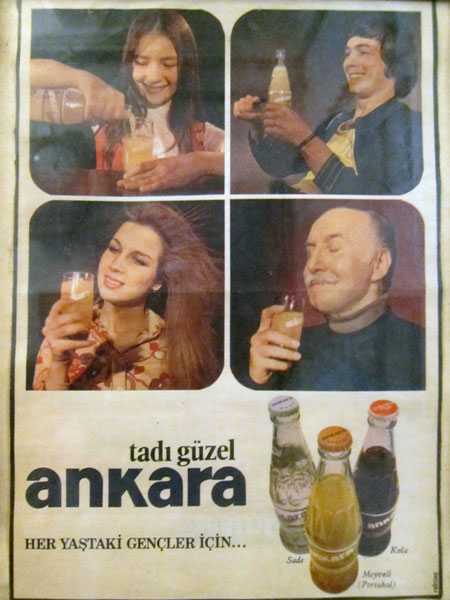

On GittiGidiyor.com – Turkey’s eBay – one cap from a vintage bottle of Ankara Gazozu is listed for 50TL, while the price for a set of four D&K Aroma Gazozu caps is 26.90TL. A handmade basket suitable for salt shakers and napkins made from dozens of gazoz caps strung together by wire sells for 40TL. As we scrolled through the listings, we started to get into the unique design on some caps, or the lack of any design whatsoever on others. The ones with errors were, naturally, priced more highly for collectors, but we sort of liked the ones that were blank – just plain, unmistakable gazoz caps. These rusty-edged, cork-lined caps were archaeological evidence of the drink’s provincial manufacture, naïve as it may have been but totally local. In a time before Efes beer and Coca-Cola caps clogged every sewer grate in the country, these caps were cherished objects. For some, evidently they still are.

In the 2011 documentary film Kapak Olsun, filmmaker Burak Serkan Çetinkaya claims that by the 1950s there were around 1,000 different gazoz producers in Turkey, where the soft drink was first introduced around the turn of the century. Medium-sized Anatolian towns often had a few different local options, while several larger cities had dozens. In these small ateliers, hand-operated machines bottled the local formula for delivery, which was sometimes done by mule. In the cultural biosphere of a small Anatolian town in the mid-20th century, when foreign imports were nonexistent, the local gazoz was not only something to be cherished; it was a source of local pride.

Scanning the list of offerings at Avam Kahvesi, we wondered about the terroir of the backwater town of Kırşehir, home of the venerable Özbağ Gazozu. In a bottle of Özbağ, is there really something delicious and specific to Kırşehir, a taste that makes it so different from a Bozdağ or Bade? Will people who prefer Bade not settle for an Uludağ? And in the 21st century, could the market really sustain the gazoz renaissance that many gazozcus dream of? Somehow, gazoz connoisseurship felt a bit like collecting records to us: the more obscure the better, damn the quality. But that would be underestimating the fervor of true gazozcus. In a noteworthy moment in Kapak Olsun, Erdal Tosun, an actor and self-proclaimed gazozcu, submits to a blind taste test of three different gazoz brands – Niğde, Bağlar and Zaman – and easily identifies each correctly. “Each is delicious, with its own unique character,” he explains.

But for all its popularity, gazoz could not compete with Coke. In the 1960s, along with Coca-Cola’s entry into the Turkish market came new regulations on soft drink production that forbade the hand-manufacturing of gazoz. Coca-Cola then cornered the market on glass bottles with an exclusive deal with the state-run glassworks monopoly, leaving many gazoz producers with no bottles to fill. Only a few dozen producers saw the light of the 21st century. Today, along with foreign enemies in the market, they must do battle with the local Cola Turka and its massive advertising budget.

We asked Barış what he thought of the Chevy Chase ad campaign for Cola Turka and whether such a stunt could ever work for a gazoz label. “No, Chevy Chase wouldn’t rouse the nostalgia maniacs we have in Turkey. For that you need a local star from the ’80s with a kitschy side, like Nuri Alço.”

Address: Çukurluçeşme Sokak 4/A, Beyoğlu

Telephone: +90 212 292 7276

Hours: Mon.-Sat. 10am-midnight; Sun. 10am-10pm

(photos by Ansel Mullins)

Like many of the 44 artists in the current Pera exhibition “Between Desert and Sea: A Selection from the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts,” which I wrote about this week for the IHT’s Middle East pages, Mr. Durra had gone to Europe as a young man, in his case to Rome, to study art. After all, there were no formal art schools in Jordan. It wasn’t until decades later, in 1970, that Mr. Durra himself would found the first, the Jordan Institute of Fine Arts.

Like many of the 44 artists in the current Pera exhibition “Between Desert and Sea: A Selection from the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts,” which I wrote about this week for the IHT’s Middle East pages, Mr. Durra had gone to Europe as a young man, in his case to Rome, to study art. After all, there were no formal art schools in Jordan. It wasn’t until decades later, in 1970, that Mr. Durra himself would found the first, the Jordan Institute of Fine Arts.