London Book Fair: Elif Shafak on Turkey’s progress

-

Elif Shafak

- The Guardian

- Photograph: Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

As a Turkish woman writer in England there are two questions about my country that I hear

With Turkey the focus of this year’s London Book Fair, Elif Shafak says her country is starting to find its voice

often: are women equal to men and are words free? Two different subjects that receive the same answer: “Yes and no, concurrently.”

Elif Shafak says Turkey has an amazing ability to reinvent itself in a short period of time.

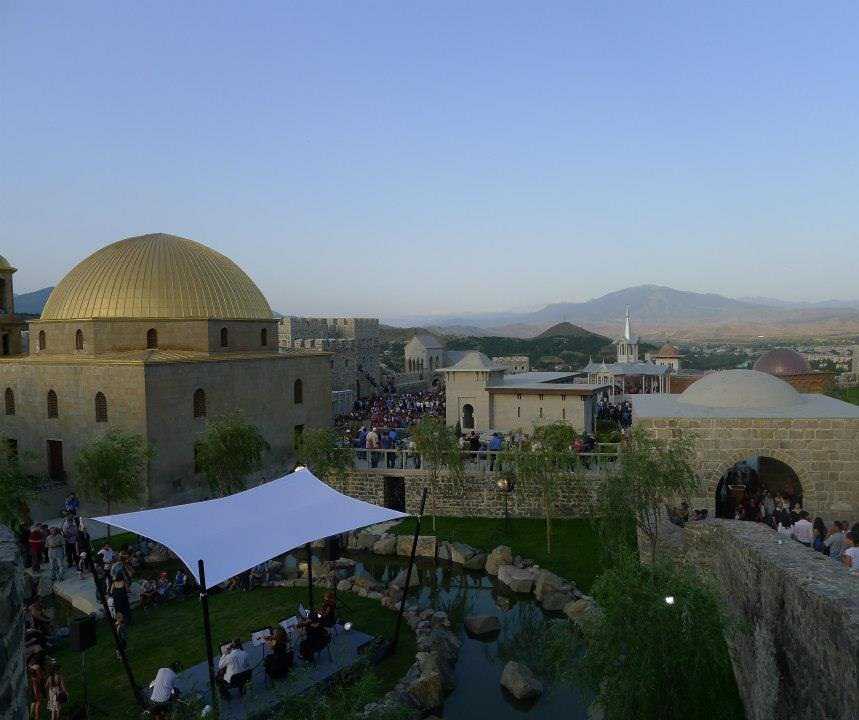

Turkey is a country of mesmerising contrasts, colours and conflicts. It’s a running joke for us to liken our progress and modernity to the Mehter – the Ottoman military band that once inspired western classical composers, such as Mozart. The band’s march consisted of two steps forwards, one step backwards. Thus we proceed in Turkey when it comes to basic freedoms and human rights.

The country is going through a historical transformation. The conflict with the Kurdish separatists, which killed more than 40,000 people and traumatised many more, is being resolved. Until recently, this would have been a dream. Prime Minister Recep Tayyib Erdogan and the AK Party have taken considerable political risks to authorise negotiations with the jailed Kurdish leader Abduallah Öcalan. They have been aided by the fact that, increasingly, more people on both sides are tired of violence and antagonism.

For way too long, Turkish ultra-nationalism and Kurdish ultra-nationalism have fed off each other, keeping the country in a vicious circle and spreading fear, bigotry and xenophobia. Turkish official ideology has systematically denied the existence of Kurds and the Kurdish language. That is no longer the case. Books, magazines, publications on “The Kurdish Question” fill the shelves. Whereas in the past it was unthinkable to question the army as an institution, that, too, has changed. The army has been confined to military and strategic matters, as it should be in any true democracy.

Nonetheless, other things are slow to change. Meeting with PEN international delegation president, Abdullah Gül, he expressed concerns about the obstacles to freedom of speech – the trials, and in some cases the incarceration, of writers, journalists and publishers. “These developments sadden me,” he said. Article 301 of the Turkish penal code, which punishes anyone who “insults Turkishness” with up to three years in prison, has been noticeably restricted in practice, though not abolished. It is not as easy as it used to be to press charges against a writer or journalist for their words since it now requires the approval of the minister of justice. However, the law hovers above our heads like the sword of Damocles. Some citizens feel “insulted” at the slightest critical remark about the state, government or our ancestors. Prosecutors take their applications seriously, and the vagueness of the law only deepens the problem.

A similar broadness can be observed in the anti‑terror laws. The distinction between those who resort to terrorism and those whose only “sin” is to speak their minds is not fully recognised. Ragip Zarakolu, the founder of a publishing house famed for supporting minority issues and a Nobel peace prize nominee, spent six months in prison last year. Social media is also fraught with danger. The composer and pianist Fazil Say appeared in court on charges of blasphemy and insulting religious values because of a tweet he sent.

Obscenity trials are another hurdle for writers and artists. The Turkish publication of Chuck Palahniuk’s novel Snuff – rendered Death Porn in Turkish – saw both its translator and publisher in court. The publication of a translation of The Soft Machine by William Burroughs was accused of obscenity, but the trial was postponed.

Just recently a complaint has been filed against two intellectuals – Robert Koptas, the editor of the Armenian newspaper Agos, whose previous editor Hrant Dink was assassinated, and Ümit Kivanç, leftist-liberal journalist – because one citizen complained that the words they uttered on TV were “insulting”, adding “clearly they must be Armenians”.

There is a growing concern that the press is not as diverse as it used to be and that alternative voices are heard less and less. Self-censorship is a subject we rarely discuss, although clearly we have to: last month Hasan Cemal, a veteran journalist and critical thinker, left his newspaper, Milliyet.

Even if the majority of the cases do end in acquittal, the judicial process is too lengthy. Writers, journalists, translators and publishers are no strangers to prosecutors’ offices. And then they have to suffer attacks from extremist newspapers. One major hurdle is the old laws, many of which date back to the 1980 military coup d’etat. We urgently need a new, egalitarian, pluralistic, and more democratic constitution. Only this can help Turkey to move up in the World Press Freedom Index where it is ranked 154th out of 179 countries.

Yet at the same time countless books and magazines are published on subjects that until recently were taboo. Minority rights, the army, domestic violence, homophobia – publications and discussions follow one another. Turkey has an amazing ability to reinvent itself in a surprisingly short time. Of one thing we can be certain: young and dynamic, perched delicately on the threshold of east and west, Turkey’s civil society is anything but silent.

• Turkey is the market focus of this year’s London Book Fair, 15-17 April, Earls Court, London SW5.

via London Book Fair: Elif Shafak on Turkey’s progress | Books | The Guardian.