THE GRAND BAZAAR I’ll never forget the first time I saw it. I was with a bunch of other tourists, at a dead run, trying to keep up with Mike.

Grand Bazaar Fountain ©2003 Trici Venola.

WITH MIKE IN THE GRAND BAZAAR

We charge at breakneck pace through a big arched gate, down a promenade lined with cheap fezzes and fake harem stuff, past all the gaudy scarves and baubles and Vegas gold. We run up through a forest of painted columns on a steep stone incline lined with underwear and carpet shops, Mike’s harem for the day of Americans, eager for exotica and bargains, all staying at Kybele, the hotel he runs with his family in Sultanahmet.

It’s a rare Turk who loves old stuff. In a country full of antiquities, modernity is prized. But Mike wears antique silver and scarves and jeans. The other merchants stare at him from their suits. The beaded pillbox hat throws them. ‘They don’t know the difference between Fundamentalist and Hippie,’ he snorts.

It’s a rare Turk who loves old stuff. In a country full of antiquities, modernity is prized. But Mike wears antique silver and scarves and jeans. The other merchants stare at him from their suits. The beaded pillbox hat throws them. ‘They don’t know the difference between Fundamentalist and Hippie,’ he snorts.

Happy Mike ©2001 Trici Venola

We land at tilting tables in the thick aroma of spiced meat and gaze up at the yellow arched ceilings. The Grand Bazaar was started by Mehmet the Conqueror in 1461 and has been evolving ever since. It was the first mall and is still going strong. It has over three thousand shops. As many as 400,000 people pour daily through the dozens of arched entrances, but only four of them can fit in some of these shops where there are things like I’ve only seen in museum cases. After lunch we trot past many merchants. There are 26,000 people working here and they all want us to buy something.

Mustafa In the Grand Bazaar ©2011 Trici Venola.

They stare with amazed chagrin at the short bearded Turkish man in his quasi-Fundamentalist gear and his train of great big gorgeous American cows. All that money and they can’t get at it. Galvanized, they shriek, “Nize carpet! A sell you nize carpet! ” “Leather, Lady? Good leather! ” “Hey Lady! Dress! ” “Lady! Lady!” –holding up a pair of panties, making them dance– as we pant up the steep slope and turn left through an archway into another world of carpets and electrical appliances and high heels–high heels? — up a long staircase, across lumpy tarpaper roofs and up a final, very old stone flight of stairs, worn in the middle and cracked on the edges, past a sort of gatehouse where a young man mends shoes.

Mike In the Grand Bazaar ©2000 Trici Venola

Small boys run up and down with round tin trays loaded with tulip glasses, full and empty. The entire Turkish buying ritual is flavored for me with this strong Turkish chai—made in a samovar and served scalding in a small glass. The little tulip glass is presented in a saucer shaped like a flower, with two or three cubes of sugar and a tiny tin spoon. If you don’t put the sugar into the tea, it melts and makes the bottom of the glass all sticky, so I’ve developed a taste for sweet tea.

The Ringmaker ©2000 Trici Venola

At the top of the stairs is a maze of old hallways, some roofed and some catwalked through the open air. We’re at the top of the bazaar. On a roof overlooking a grapevined courtyard is a tent full of textiles.

Osman’s Rooftop Textiles ©2004 Trici Venola

It’s here that I buy Koran covers for my sketchbooks. Each cover was made by someone by hand, some caravan housewife or goatherd alone in the hills, pieced together from remnants and embroidered and lined, to cover a precious book.

There’s a shop up here full of brass: bowls and pots, old and new, and the scimitar-like crescents from the tops of mosques. There’s a shop full of dangling jingling jewelry, where they sell old silver ornaments by weight and your knees are jammed against your companion’s. I drink my chai and look out past hanging ceramic tent ornaments through a murky window at the cats slinking through sunbleached grass growing on the wall opposite. There’s a place where I find a pair of soft backless shoes, the kind with toes that point up, in glowing red leather.

There’s a shop up here full of brass: bowls and pots, old and new, and the scimitar-like crescents from the tops of mosques. There’s a shop full of dangling jingling jewelry, where they sell old silver ornaments by weight and your knees are jammed against your companion’s. I drink my chai and look out past hanging ceramic tent ornaments through a murky window at the cats slinking through sunbleached grass growing on the wall opposite. There’s a place where I find a pair of soft backless shoes, the kind with toes that point up, in glowing red leather.

Up Top at the Grand Bazaar ©2003 Trici Venola

Dusty Old Shop ©1999 Trici Venola

Then down a narrow dingy hall to the very last shop: a closet with two dusty glass cases and some shelves. First chai, then out come small battered newspaper bundles. They could be anything. Last time it was a blackened bronze bracelet, pitted with age, grooved, with an opening just big enough for my wrist. I slid it on and it was mine. I imagined it on a wrist that turned black along with it. “It will clean itself from your body,” said the man through Mike. “I think maybe a toothbrush and some toothpaste,” I said. Mike was horrified. “You’ll ruin the patina!” he exclaimed, “No toothbrush! Just wash it when you wash your hands and it will turn to gold.” I haven’t taken it off much since I got it in Istanbul so long ago. It’s been in salt water and sun and sleep, sickness, love, heartbreak, and mayhem with me, and like everything else clotted and dark in my life it is slowly but unmistakably beginning to show the glint of gold.

—

KAPALICARSI: THE COVERED BAZAAR

This antique postcard and the new one above coincidentally show the same view.

Grand Bazaar is, in Turkish: Kapalicarsi, literally Covered Bazaar. In oldtime Istanbul, according to classic Islamic tradition, anything or anyone beautiful and precious was covered. Delightful houses were humble on the outside. Gardens hid behind walls. Women were veiled. Those Koran covers I buy for my sketchbooks follow the same priciple. This had everything to do with how the Bazaar evolved.

Gulersoy Collection. Shoe Sale ©1980 Aydin Erkmen

Women shoppers could not be in an enclosed, Western-type shop with a merchant. So thewhole bazaar was enclosed. What a concept! All the precious things covered at once! The stalls were built into the walls of the streets, with wooden covers– divans– flipped up to display the goodies for sale, which were heaped and hung there with no glass barrier: a feast of color and texture to dazzle and delight. The women could bargain out in the open, protected from weather and gossip.

Gulersoy Collection. Divan Row c1850

Through pools of light from the high windows, horses, donkeys, carriages and the occasional camel were all ridden through the Bazaar. Down each avenue was a trough for water and waste. You can see traces of these still, under the modern floor tiles. Westernization brought imitation of Europe, so shops were built out into the streets, turning most of them into narrow labyrinths. Despite modern electrical wiring these have an undersea feel on dark winter days. I’ve been in the Bazaar in a blackout, though, and you can always find your way because of the windows. Here’s Muhammed in front of his shop Ak Gumus on Yesil Direkli Street up by the Post Office, looking down Sari Haci Hasan Street.

Momo Outside His Shop ©2011 Trici Venola

Here is beloved tissue seller Gemici from the same spot looking up.

Everybody Loves Gemici ©2011 Trici Venola

OLD VIRTUES & THE TOUT POLICE

Many visitors today are intimidated by the loud aggressive persistance of the touts, the guys that stand in their doorways and exhort, charm, plead, annoy and wheedle you into looking. But they can’t follow you. The Tout Police will Get Them, and I’m told it’s a hefty fine. The Tout Police are the last vestige of the old ways. In Ottoman days of yore, pushing ones work or goods was anti-Islam, as was advertising. The Bazaar Greeks were the aggressive traders. Turks would sit silently and smoke nargile while you shopped, only showing what you asked to see.

Many visitors today are intimidated by the loud aggressive persistance of the touts, the guys that stand in their doorways and exhort, charm, plead, annoy and wheedle you into looking. But they can’t follow you. The Tout Police will Get Them, and I’m told it’s a hefty fine. The Tout Police are the last vestige of the old ways. In Ottoman days of yore, pushing ones work or goods was anti-Islam, as was advertising. The Bazaar Greeks were the aggressive traders. Turks would sit silently and smoke nargile while you shopped, only showing what you asked to see.

Traders ©1980 Aydin Erkmen

Freedom from jealousy and indifference to profit were Islamic virtues. A French visitor to Istanbul in 1830 wrote with astonishment that. after he had selected a wallet, the Turkish shop owner advised him to buy a better one for the same price from his neighbor. It wasn’t uncommon for a shopowner who had sold something that day to send business to someone who hadn’t.

Democracy and Westernization brought the present exhortionate hullaballoo. I find that I have come to view it with affection. The touts can tell where you’re from at a glance, and they have stock phrases. We retaliate. They say, “Excuse Me!” And we say, “Okay, you’re excused.” They say, “You dropped something: my heart!” We stomp on the floor and grind it to bits, grinning. They stagger and clutch at their chests, and nobody stops for a minute. On top of this cacophony, down in the bottom of the Bazaar they call out the exchange, fluctuating figures bawled out in Turkish, letting me know I’m not in Kansas anymore.

COMMISSION MAN Sultan Abdulhamid’s reign, in the early 1900s, brought the Translator Guides. These would follow and buttonhole the visitor, advising him as to what he wanted. Then they’d translate from the shop owner and take a commission on the sale. They were multilingual with amazing memories, remembering the tourist from visit to visit: where they stayed, what they ate, etc, and they drove everyone crazy. People would buy things just to get rid of them. The modern-day equivalent is the Commission Man, the guy who dogs you on the street trying to steer you to a carpet shop. Most are obnoxious jerks, but some are classy and charming.

Inside the Wall ©2003 Trici Venola.

Democracy also brought Advertising. Turkey’s excessive signage is notorious, but it could be worse. This horrifying photo is what the Grand Bazaar looked like in 1979.

Billboards in the Grand Bazaar ©1980 Celik Gulersoy

This abomination vanished with military coup of the early 1980s. Some general must have had good taste. Shortly afterwards the Bazaar interior was covered with cheerful yellow and painted with classic Ottoman tulip designs by art students. I have drawn this tulip painting many times. It’s beautiful, but I think they must have all gone mad.

ARCHITECTURE

Old Corner in the Bazaar ©2008 Trici Venola

Istanbul’s Old City is Greco-Roman geometry overlaid with Ottoman clusters. The Bazaar is a fine example of an Ottoman cluster. It was not planned or built all at once but evolved over time, built as needed in a meandering fashion by a nomadic culture.

Gulersoy Collection. Bazaar Roof 1976

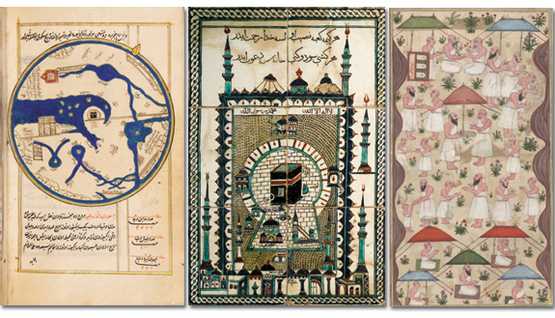

It started from two giant brick enclosures: the Bedestens. This famous 16th Century miniature shows the Cevahir Bedesten, or Inner Bedesten, at upper center. The smaller Sandal Bedesten, just inside the Norosmaniye Gate, is harder to see. The streets between are not yet roofed. Notice the Hippodrome with obelisks and Snake Column at upper right, and the City Walls and Marmara at lower right.

Gulersoy Collection. Two Bedestens in Istanbul, 16th-century miniature by Nasuh-es-Silahi.

The Sandal Bedesten was named for thread from Bursa the color of sandalwood. Here’s the Sandal Bedesten now. The renovation is boring but the people are not.

The big one in the center, Inner Bedesten, is now the Old Bazaar. A Byzantine Eagle at the Southern entrance has given rise to a belief that it was originally a Byzantine structure, but the Eagle could as easily been lifted from somewhere else. These two Bedestens were built by Mehmet the Conqueror, and gradually the streets between were roofed over and the sprawling structure organized into trades. Here’s the oldest photo ever found of the Bazaar’s outside, from 1856. That’s the Blue Mosque at the top. The Sandal Bedesten is below it at left, the Great Bedesten at center, and our old friend Buyuk Valide Han down front, outside the Bazaar.

The big one in the center, Inner Bedesten, is now the Old Bazaar. A Byzantine Eagle at the Southern entrance has given rise to a belief that it was originally a Byzantine structure, but the Eagle could as easily been lifted from somewhere else. These two Bedestens were built by Mehmet the Conqueror, and gradually the streets between were roofed over and the sprawling structure organized into trades. Here’s the oldest photo ever found of the Bazaar’s outside, from 1856. That’s the Blue Mosque at the top. The Sandal Bedesten is below it at left, the Great Bedesten at center, and our old friend Buyuk Valide Han down front, outside the Bazaar.

Gulersoy Collection. Grand Bazaar in 1856

The Inner Bedesten was built with stalls for animals, which are now very tony shops. Here’s Nick in his famous Calligraphy Shop, which features a wall of photos of celebrity customers: movie stars, bestselling authors and world leaders, including the Clintons.

Nick’s Calligraphy Shop ©2010 Trici Venola

So the Bazaar continued to evolve. Each section was dedicated to a particular trade. Weapons, shoes, cloth, clothing, brass ornaments, jewelry, gold and silver, perfumes, foodstuffs, and slaves.

Gulersoy Collection. The Shoemakers’ Market

The trades were organized into guilds. Each kept to its own area of the Bazaar. Here’s the Presentation of Artisans to the Sultan, back in the day.

Gulersoy Collection. Artisans Parade for the Sultan at Ay Medani c1550

The present Bazaar is zoned by what is sold where. A store in the silver zone can’t sell you gold.

Mao of Grand Bazaar

Many businesses are passed down from father to son for centuries. Here are several generations of the Sengor family, who have been selling carpets on Takkeciler Street for a very long time. I drew the mother and grandfather from photos.

Sengor Family in the Grand Bazaar ©2003 Trici Venola

Another old photo from the end of the 19th century:

Gulersoy Collection. Grand Bazaar c1880

This has got to be where Sark Cafe is now. Here it is from the other direction.

I went all over the Bazaar with my book of old photos, conferring with groups of fascinated salespeople and taking pictures. The engraving below is likely near the mosque up on Yaglikcilar Street.

Gulersoy Collection. Grand Bazaar (Women in White)

That big dark center arch probably went in an earthquake. Here’s the spot today:

Here’s another place I love:

Here’s another place I love:

Gulersoy Collection. Grand Bazaar (High Arch with Cat)

There are 13 hans within in the Grand Bazaar. You go up or down a twisty little alley, your shoulders brushed by lame, beaded fringe, bunches of shoes and so forth, and come out into a courtyard surrounded by fascinating shops. Many pussycats live in these hans, fed and sheltered by generations of shopkeepers.

There are 13 hans within in the Grand Bazaar. You go up or down a twisty little alley, your shoulders brushed by lame, beaded fringe, bunches of shoes and so forth, and come out into a courtyard surrounded by fascinating shops. Many pussycats live in these hans, fed and sheltered by generations of shopkeepers.

Each han has its own personality. This little one, Cukur Han, has a plaque stating it’s 19th Century, but the wall and archway look to be much older. See the carved Roman chunk above the window and the little column shoved in sideways?

Window at Cukur Han ©2010 Trici Venola

I found this when visiting my friends Emin and Nurettin at Nurem in Cukur Han, wholesale traders and manufacturers of suzanis (embroidered tribal hangings), ikat (woven fabric that resembles tie-die), and patchwork.

The Ikat Princes ©2011 Trici Venola

The present bazaar boasts its own post office– the PTT– a police department, and modern plumbing, as well as the mosque and fountains which have been there for centuries.

On Fridays, the Imam’s sermon is broadcast, and half the bazaar gets out in the aisles to pray. Rather than prayer rugs the faithful use pieces of cardboard, rising and falling in salaams to Allah, while people step over them and business goes on as usual.

Gulersoy Collection. At the Mosque ©1980 Aydin Erkmen

In 1894 Istanbul suffered a terrible earthquake. The Bazaar lost much of its architecture, which accounts for wonderful pictures like this:

I always wondered what happened here and now I know. Here’s a photo from 1894:

Gulersoy Collection. After the Earthquake, 1894

SECURITY The Bazaar is not and never has been open at night for any reason. During the reign of Abdulhamid, police had to break in because of a fire. In 1913, poet Pierre Loti was locked inside and had to talk his way out. And in 2006, a friend left my birthday present in his shop and could not for love nor money get in any of the four entrances he tried.

Gulersoy Collection. In the Bazaar, 19th century by Trezio

Nowadays, you’re safer in the Grand Bazaar than most places. Merchants eager for happy tourists brook no thieves. A few years ago, a mob of men, women and children flailed and stomped a purse snatcher before the guards could do anything. The battered thief was lucky to escape with his manhood intact.

The Coca-Cola Kiosk ©2009 Trici Venola

THE AESTHETIC POLICE

The Aesthetic Police: a concept of a group with total power who would enforce charm and good taste on benighted areas worldwide.You could call them in, and the hideous shopping center that’s replacing that fine old tree-hung neighborhood would be stopped in an instant. Hideous restoration would cease. Trees would be trimmed properly and not amputated into bad sculpture. Billboards would be obliterated. There would be a death penalty for littering. Aesthetic Police: I always thought that this was just an expression. But then I encountered Celik Gulersoy.

Gulersoy Collection. Artisans Parade for the Sultan at Ay Meydani, c1550

President of Turkey’s Auto Club for many years, he was a force in the community. He stood down an Istanbul governor who was armed with bulldozers and a prime minister, saving those 17th-century houses behind Hagia Sophia, now Konuk Hotel. He created the chandelier-hung Istanbul Library there in Sogukçesme Street and found the Byzantine cistern that is now Sarniç Restaurant. He created Green House Hotel and its fountained garden. He longed for a generation of young people who would value and nurture trees, as the Ottomans did. He fought tree-butchers and asphalt-layers and excessive signage and all those who would uglify and kitsch up the Great Mysteries of this ancient place. I never got to meet Mr Gulersoy, but I wish he was King of the World.

Celik Gulersoy loved the Grand Bazaar so much he wrote a book about it: The Story of the Grand Bazaar. A battered, borrowed copy provided much of the material shown here. Thanks to Gazanfer Bey, manager of Konuk Hotel, and the Staff of Istanbul Library, I now own the last copy in Istanbul. Many thanks to them for their help in researching this post. All the time I was writing it, I was hearing that song from Kismet:

Baubles, bangles, hear how they jing jingalinga Baubles, bangles, bright shiny beads! Sparkles, spangles, my heart will sing singalinga Wearing baubles, bangles and beads! I’ll glitter and gleam so, make somebody dream so….

–Robert Wright and George Forrest, 1953

Yasmin at Cafe Ist ©2003 Trici Venola

——————————-

All Trici Venola’s drawings are Plein Air, drafting pens in sketchbooks 7 X 20″ / 18 X 52 cm. All drawings are part of The Drawing On Istanbul Project by Trici Venola. All modern photographs ©2012 Trici Venola. Thanks for reading this post. We love your comments.

Share this:

- StumbleUpon

- Facebook10

- Twitter3

- Email

- Print

It’s a rare Turk who loves old stuff. In a country full of antiquities, modernity is prized. But Mike wears antique silver and scarves and jeans. The other merchants stare at him from their suits. The beaded pillbox hat throws them. ‘They don’t know the difference between Fundamentalist and Hippie,’ he snorts.

It’s a rare Turk who loves old stuff. In a country full of antiquities, modernity is prized. But Mike wears antique silver and scarves and jeans. The other merchants stare at him from their suits. The beaded pillbox hat throws them. ‘They don’t know the difference between Fundamentalist and Hippie,’ he snorts.

There’s a shop up here full of brass: bowls and pots, old and new, and the scimitar-like crescents from the tops of mosques. There’s a shop full of dangling jingling jewelry, where they sell old silver ornaments by weight and your knees are jammed against your companion’s. I drink my chai and look out past hanging ceramic tent ornaments through a murky window at the cats slinking through sunbleached grass growing on the wall opposite. There’s a place where I find a pair of soft backless shoes, the kind with toes that point up, in glowing red leather.

There’s a shop up here full of brass: bowls and pots, old and new, and the scimitar-like crescents from the tops of mosques. There’s a shop full of dangling jingling jewelry, where they sell old silver ornaments by weight and your knees are jammed against your companion’s. I drink my chai and look out past hanging ceramic tent ornaments through a murky window at the cats slinking through sunbleached grass growing on the wall opposite. There’s a place where I find a pair of soft backless shoes, the kind with toes that point up, in glowing red leather.

Many visitors today are intimidated by the loud aggressive persistance of the touts, the guys that stand in their doorways and exhort, charm, plead, annoy and wheedle you into looking. But they can’t follow you. The Tout Police will Get Them, and I’m told it’s a hefty fine. The Tout Police are the last vestige of the old ways. In Ottoman days of yore, pushing ones work or goods was anti-Islam, as was advertising. The Bazaar Greeks were the aggressive traders. Turks would sit silently and smoke nargile while you shopped, only showing what you asked to see.

Many visitors today are intimidated by the loud aggressive persistance of the touts, the guys that stand in their doorways and exhort, charm, plead, annoy and wheedle you into looking. But they can’t follow you. The Tout Police will Get Them, and I’m told it’s a hefty fine. The Tout Police are the last vestige of the old ways. In Ottoman days of yore, pushing ones work or goods was anti-Islam, as was advertising. The Bazaar Greeks were the aggressive traders. Turks would sit silently and smoke nargile while you shopped, only showing what you asked to see.

The big one in the center, Inner Bedesten, is now the Old Bazaar. A Byzantine Eagle at the Southern entrance has given rise to a belief that it was originally a Byzantine structure, but the Eagle could as easily been lifted from somewhere else. These two Bedestens were built by Mehmet the Conqueror, and gradually the streets between were roofed over and the sprawling structure organized into trades. Here’s the oldest photo ever found of the Bazaar’s outside, from 1856. That’s the Blue Mosque at the top. The Sandal Bedesten is below it at left, the Great Bedesten at center, and our old friend Buyuk Valide Han down front, outside the Bazaar.

The big one in the center, Inner Bedesten, is now the Old Bazaar. A Byzantine Eagle at the Southern entrance has given rise to a belief that it was originally a Byzantine structure, but the Eagle could as easily been lifted from somewhere else. These two Bedestens were built by Mehmet the Conqueror, and gradually the streets between were roofed over and the sprawling structure organized into trades. Here’s the oldest photo ever found of the Bazaar’s outside, from 1856. That’s the Blue Mosque at the top. The Sandal Bedesten is below it at left, the Great Bedesten at center, and our old friend Buyuk Valide Han down front, outside the Bazaar.

Here’s another place I love:

Here’s another place I love:

There are 13 hans within in the Grand Bazaar. You go up or down a twisty little alley, your shoulders brushed by lame, beaded fringe, bunches of shoes and so forth, and come out into a courtyard surrounded by fascinating shops. Many pussycats live in these hans, fed and sheltered by generations of shopkeepers.

There are 13 hans within in the Grand Bazaar. You go up or down a twisty little alley, your shoulders brushed by lame, beaded fringe, bunches of shoes and so forth, and come out into a courtyard surrounded by fascinating shops. Many pussycats live in these hans, fed and sheltered by generations of shopkeepers.

At the right of the drawing above is Ayasuluk, a 6000-year-old Paleolithic hilltop settlement.

At the right of the drawing above is Ayasuluk, a 6000-year-old Paleolithic hilltop settlement.

The earthquake-wrecked temple was further ravaged by Tamerlane’s Mongol army in 1402. Finally, in one of the poetic ironies that keep me living in Turkey, the marble of the ruined Temple of Artemis was pillaged by Justinian’s builders to create St John’s Basilica, which was in turn pillaged to create Isa Bey Mosque. This is what’s left.

The earthquake-wrecked temple was further ravaged by Tamerlane’s Mongol army in 1402. Finally, in one of the poetic ironies that keep me living in Turkey, the marble of the ruined Temple of Artemis was pillaged by Justinian’s builders to create St John’s Basilica, which was in turn pillaged to create Isa Bey Mosque. This is what’s left. The only one of these not yet to fall to an earthquake is the mosque, which stands squarely among palm trees on a hillside below the two ruined temples.

The only one of these not yet to fall to an earthquake is the mosque, which stands squarely among palm trees on a hillside below the two ruined temples.

Sphendone.The Hobbit Door ©2004 Trici Venola

Sphendone.The Hobbit Door ©2004 Trici Venola

If this structure wasn’t serviceable, it would never have survived so long. But survive it does. I sat in a playground full of shrieking children to draw this one. And as the South Face rounds over into the West Face, there’s this Wooden House Arch.

If this structure wasn’t serviceable, it would never have survived so long. But survive it does. I sat in a playground full of shrieking children to draw this one. And as the South Face rounds over into the West Face, there’s this Wooden House Arch.

This brickwork, witness to so many lives lived and passed out of recollection, gives me peace. My terrifying problems seem as ephemeral as storms on old brick. They may erode the shape into something unforeseen, but the Sphendone still stands. Roman mortar– it hardens under water.

This brickwork, witness to so many lives lived and passed out of recollection, gives me peace. My terrifying problems seem as ephemeral as storms on old brick. They may erode the shape into something unforeseen, but the Sphendone still stands. Roman mortar– it hardens under water.

Very quickly, I felt good. Here’s an email to a newly jobless Stateside friend from January 2011:

Very quickly, I felt good. Here’s an email to a newly jobless Stateside friend from January 2011:

I’m standing in line a lot these days, staring at the marauder-scarred marble in the courtyard waiting to get in, because I’m drawing from a mosaic in one of those upper galleries from 9 AM until it closes at 4:45. It’s that real famous Jesus, in The Last Judgement, a Deesus Mosaic– Jesus flanked by Mary and John the Baptist. The Jesus is a masterpiece. From a few feet away you can’t tell that the face is mosaic at all.

I’m standing in line a lot these days, staring at the marauder-scarred marble in the courtyard waiting to get in, because I’m drawing from a mosaic in one of those upper galleries from 9 AM until it closes at 4:45. It’s that real famous Jesus, in The Last Judgement, a Deesus Mosaic– Jesus flanked by Mary and John the Baptist. The Jesus is a masterpiece. From a few feet away you can’t tell that the face is mosaic at all.

Looks pretty simple, huh? Deceptive, this face. It’s wider than it seems. The eye on the right is much larger, and the pupil is toward the right, wihich makes him appear to see everywhere. The mouth is a rosebud, but not prissy at all. The features are delicate but very masculine and strong. Look at that neck! The hand is graceful but the general impression is one of power.

Looks pretty simple, huh? Deceptive, this face. It’s wider than it seems. The eye on the right is much larger, and the pupil is toward the right, wihich makes him appear to see everywhere. The mouth is a rosebud, but not prissy at all. The features are delicate but very masculine and strong. Look at that neck! The hand is graceful but the general impression is one of power.

Now across the way from the actual mosaic is a huge color photo blowup of Jesus. The next day, I camped out there where I could see closely, to draw the mosaic construction of the face. If I drew exactly what’s on the wall, I’d get a person in a mosaic suit. Drawing, I met Maria and Ioanna. They’re Cypriot Greeks, like Michael Constantinou who commissioned this piece. Gorgeous, aren’t they? Thrilled that someone knows the Greek part of Hagia Sophia’s history, and now we are all Facebook

Now across the way from the actual mosaic is a huge color photo blowup of Jesus. The next day, I camped out there where I could see closely, to draw the mosaic construction of the face. If I drew exactly what’s on the wall, I’d get a person in a mosaic suit. Drawing, I met Maria and Ioanna. They’re Cypriot Greeks, like Michael Constantinou who commissioned this piece. Gorgeous, aren’t they? Thrilled that someone knows the Greek part of Hagia Sophia’s history, and now we are all Facebook  Friends. I’d jumped up to show them something. One thing I had noticed from the original location is how the artist took into account the light coming in from the left. Here’s the Jesus as I left him on the last session.

Friends. I’d jumped up to show them something. One thing I had noticed from the original location is how the artist took into account the light coming in from the left. Here’s the Jesus as I left him on the last session.

These days I’m down at the Boukoleon in the horrible ant-infested boiling sunlight, I wrote,drawing the arch from the only accessible side, the one where the only time it’s lit from the front is early in the morning. The rest of the time the light is behind it. So I’m staring into bright sunlight trying to get the gist of the shape, the whole mind-boggling panoply of brickwork, ribs and chunks and shards of brick all fanning out in radiant lines around the arch, and up top, turrets of masonry desiccated into shapes resembling griffins and tombstones, all dark against the white blare of the sky.

These days I’m down at the Boukoleon in the horrible ant-infested boiling sunlight, I wrote,drawing the arch from the only accessible side, the one where the only time it’s lit from the front is early in the morning. The rest of the time the light is behind it. So I’m staring into bright sunlight trying to get the gist of the shape, the whole mind-boggling panoply of brickwork, ribs and chunks and shards of brick all fanning out in radiant lines around the arch, and up top, turrets of masonry desiccated into shapes resembling griffins and tombstones, all dark against the white blare of the sky. The structure of a brick arch requires that the sides of the bricks fan out above the arch. But the Byzantines, never missing a religious beat, reinforced that imagery with double and triple window arches, left bare to symbolize the Light of the Lord from within. And those double narrow marble columns? Those are Peter and Paul, holding up the church. Are you ready for that? Of course, the Boukoleon is a palace, not a church, and the brick arches show up as radiance by default, having been stripped of their former magnificence by Crusaders, Ottomans, weather and the Republic. I’d sure love to know how that place was finished off. We’ve discussed in earlier blogs how the only CGI recreation shows grey marble because there’s no record of what the

The structure of a brick arch requires that the sides of the bricks fan out above the arch. But the Byzantines, never missing a religious beat, reinforced that imagery with double and triple window arches, left bare to symbolize the Light of the Lord from within. And those double narrow marble columns? Those are Peter and Paul, holding up the church. Are you ready for that? Of course, the Boukoleon is a palace, not a church, and the brick arches show up as radiance by default, having been stripped of their former magnificence by Crusaders, Ottomans, weather and the Republic. I’d sure love to know how that place was finished off. We’ve discussed in earlier blogs how the only CGI recreation shows grey marble because there’s no record of what the  finish was. The heap of broken stuff under the arch has marble every color of the rainbow, and I’ll bet that a lot of that was on the outside walls. There were huge lions on the sea balconies. There were probably other statues as well, although the Emperor Theophilos, who built the Boukoleon in the mid-9th century, appears to have been an Iconoclast: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F8pbLPVZWko

finish was. The heap of broken stuff under the arch has marble every color of the rainbow, and I’ll bet that a lot of that was on the outside walls. There were huge lions on the sea balconies. There were probably other statues as well, although the Emperor Theophilos, who built the Boukoleon in the mid-9th century, appears to have been an Iconoclast: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F8pbLPVZWko

arch looks like a standing lion. I could not get this right. Nobody would ever know but me, since the piles of stone are crumbling so fast you can see it happen. It is possible to preserve a ruin without destroying its surface integrity, but what will happen to this one is anyone’s guess. Around here they’re repairing 10th-century stonework with brand new stone blocks. So God help the Boukoleon, and I’m drawing as fast as I can.

arch looks like a standing lion. I could not get this right. Nobody would ever know but me, since the piles of stone are crumbling so fast you can see it happen. It is possible to preserve a ruin without destroying its surface integrity, but what will happen to this one is anyone’s guess. Around here they’re repairing 10th-century stonework with brand new stone blocks. So God help the Boukoleon, and I’m drawing as fast as I can.

and here’s the same drawing, expanded on today:

and here’s the same drawing, expanded on today:

The Cross works fine on finding where to draw the stuff, but it’s only half the battle. The other half is finding a unit from which to measure proportion. It’s really easy to lose track of what size things are, so I’m constantly measuring, comparing. My first unit on this drawing is the shape of the inner arch on the far left. Here, I’ve traced it in blue to show how to use it:

The Cross works fine on finding where to draw the stuff, but it’s only half the battle. The other half is finding a unit from which to measure proportion. It’s really easy to lose track of what size things are, so I’m constantly measuring, comparing. My first unit on this drawing is the shape of the inner arch on the far left. Here, I’ve traced it in blue to show how to use it: See? That space is exactly the same width as the pillar. It’s the same width as the distance to the pillar. It’s half the width of the space past the pillar, and so on. Find something you’ve already drawn, and measure everything else by that. To measure, I hold up my pen in front of what I’m drawing and indicate with my thumbnail on it how big it is. Then I move the pen and the thumb over to what I need to draw next, and see if it’s bigger or smaller. Works like a charm. Make sure you’re not tilting the pen away from you, or your proportions will be off.

See? That space is exactly the same width as the pillar. It’s the same width as the distance to the pillar. It’s half the width of the space past the pillar, and so on. Find something you’ve already drawn, and measure everything else by that. To measure, I hold up my pen in front of what I’m drawing and indicate with my thumbnail on it how big it is. Then I move the pen and the thumb over to what I need to draw next, and see if it’s bigger or smaller. Works like a charm. Make sure you’re not tilting the pen away from you, or your proportions will be off. So back to portraits– I had to use the loo, and Semavar Cafe is closed for the Bayram. So I walked down to the next restaurant. The security guy looked familiar. Oh, that guy, who keeps showing up during my sessions at the Boukoleon asking to be drawn. Sigh. I’d like to use that loo again with no hassle, so I made his day. As I’ve mentioned, with most portraits I draw just the basics and finish up later. Several people have asked to see a portrait ‘before,’ so here’s Celal, thrilled and rock-steady.

So back to portraits– I had to use the loo, and Semavar Cafe is closed for the Bayram. So I walked down to the next restaurant. The security guy looked familiar. Oh, that guy, who keeps showing up during my sessions at the Boukoleon asking to be drawn. Sigh. I’d like to use that loo again with no hassle, so I made his day. As I’ve mentioned, with most portraits I draw just the basics and finish up later. Several people have asked to see a portrait ‘before,’ so here’s Celal, thrilled and rock-steady.

I’m making this work better simply by blackening certain areas and strengthening certain lines, while looking at the actual Boukoleon. It really helps to look at the drawing upside-down, in a mirror, and from across the room. You can immediately spot what needs to be done.

I’m making this work better simply by blackening certain areas and strengthening certain lines, while looking at the actual Boukoleon. It really helps to look at the drawing upside-down, in a mirror, and from across the room. You can immediately spot what needs to be done.

This piece is really busy because of the accuracy. In line art, you’ve got two choices: lines and no lines. There’s a kind of code that develops: dots mean one sort of surface, hatching another. In this piece I used stippling for mortar. For brick, I used hatching. And now we’re going to talk about foliage.

This piece is really busy because of the accuracy. In line art, you’ve got two choices: lines and no lines. There’s a kind of code that develops: dots mean one sort of surface, hatching another. In this piece I used stippling for mortar. For brick, I used hatching. And now we’re going to talk about foliage.

The Boukoleon tells us a lot by its age and decrepit condition. We can see how the rainwater fountained down by the way it carved troughs in the bricks. The big stones at the bottom record the thrash of waves in storms. The blackened areas tell us of past horrors of destruction. The layers of brick and stone are clues to its construction. The lines of stress and weight tell us how a building 1200 years old can survive earthquakes, fires, explosions, partial demolition by dynamite, and the constant vibration from the trains running through its truncated guts.

The Boukoleon tells us a lot by its age and decrepit condition. We can see how the rainwater fountained down by the way it carved troughs in the bricks. The big stones at the bottom record the thrash of waves in storms. The blackened areas tell us of past horrors of destruction. The layers of brick and stone are clues to its construction. The lines of stress and weight tell us how a building 1200 years old can survive earthquakes, fires, explosions, partial demolition by dynamite, and the constant vibration from the trains running through its truncated guts.

four feet tall, with no neck and thick rubbery lips, and he undoubtedly stank. He refused all comfort, being one of those Christians who believed in rigid asceticism. He slept in a tiger skin and eschewed women, wine, and good food. Nevertheless, Theophano prevailed. “The people love you,” she said, “if you want, they’ll crown you Emperor.” And so it was done, with a grand processional from the Triple Gate all through the city to Hagia Sophia, where he was coronated on the great dais there.

four feet tall, with no neck and thick rubbery lips, and he undoubtedly stank. He refused all comfort, being one of those Christians who believed in rigid asceticism. He slept in a tiger skin and eschewed women, wine, and good food. Nevertheless, Theophano prevailed. “The people love you,” she said, “if you want, they’ll crown you Emperor.” And so it was done, with a grand processional from the Triple Gate all through the city to Hagia Sophia, where he was coronated on the great dais there. Six years later he was killed by Theophano, his head displayed on a pike before an angry mob, his body thrown out of a window, likely from this very palace. He had insisted that the people continue to behave as though they were still at war, practicing rigid economies and prayers, and they wanted to enjoy life. He was Oliver Cromwell. He was soon hated. He forced the people to build a wall from the Great Palace, next to the Hippodrome where the Blue Mosque is now, all the way down to the Boukoleon on the sea, ending at the Lighthouse, cutting the people off. The Wall of Nicephorus Phokas still exists in places. It’s hollow, a great enclosed walkway the size of a roofed street, big enough for an unpopular, grandiose upstart to walk with his army. But it didn’t save him. The people would have killed him–one source says they did– If Theophano hadn’t done the job. From those contemporary physical descriptions I wonder that it took her six years. On his tomb was carved “You conquered all but a woman.”

Six years later he was killed by Theophano, his head displayed on a pike before an angry mob, his body thrown out of a window, likely from this very palace. He had insisted that the people continue to behave as though they were still at war, practicing rigid economies and prayers, and they wanted to enjoy life. He was Oliver Cromwell. He was soon hated. He forced the people to build a wall from the Great Palace, next to the Hippodrome where the Blue Mosque is now, all the way down to the Boukoleon on the sea, ending at the Lighthouse, cutting the people off. The Wall of Nicephorus Phokas still exists in places. It’s hollow, a great enclosed walkway the size of a roofed street, big enough for an unpopular, grandiose upstart to walk with his army. But it didn’t save him. The people would have killed him–one source says they did– If Theophano hadn’t done the job. From those contemporary physical descriptions I wonder that it took her six years. On his tomb was carved “You conquered all but a woman.”

Why? For drama. Artistic license, if you will. Now some of this is allowable. We are attempting to convey mood and accuracy, and we have jettisoned color, mass and one of the three dimensions. We have black and white and we have line. So there’s got to be some compensation. OK, so now it’s dramatic, but I forgot something about perspective. I can’t believe it, but I did.

Why? For drama. Artistic license, if you will. Now some of this is allowable. We are attempting to convey mood and accuracy, and we have jettisoned color, mass and one of the three dimensions. We have black and white and we have line. So there’s got to be some compensation. OK, so now it’s dramatic, but I forgot something about perspective. I can’t believe it, but I did.

So I did what all artists do, and I’m telling you about it: I faked it. That’s pretty much what it looks like, at the top left, but it’s not accurate. There are a whole lot more bricks drawn than are actually there. I had to make up the difference between the forced-perspective left top corner of the Left Portal, and the stuff below it, which I built on the Cross. So if you’re looking to rebuild the Boukoleon as the Byzantines did, don’t look at this part. Look at the rest.

So I did what all artists do, and I’m telling you about it: I faked it. That’s pretty much what it looks like, at the top left, but it’s not accurate. There are a whole lot more bricks drawn than are actually there. I had to make up the difference between the forced-perspective left top corner of the Left Portal, and the stuff below it, which I built on the Cross. So if you’re looking to rebuild the Boukoleon as the Byzantines did, don’t look at this part. Look at the rest.