by Fabio De Propris

(Swans – June 20, 2011) The first novel of Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk has yet to be published in English. This is a pity since Cevdet bey ve Oğulları (“Cevdet Bey and His Sons”) lays the foundation from which the unified structure of his work rises. Pamuk’s theme, as always, is the never ending dialectic within Turkey between East and West. For all of Anatolia lies on the Asian side of the Bosphorus while Istanbul, the commanding center, forms a great blot on the European side. The Pamuk Family Building rises there in the city’s elegant Nishantashi quarter. In one of its rooms the author sat down with pen and paper and began to create his literary world. He was twenty and had given up his ambition to be a painter. In Istanbul (2003) he tells us of his childhood and youth until 1975. Closed in his room from 1974 to 1978, he wrote Cevdet bey ve Oğulları, to be published in 1982. There’s something of a paradox in the fact that his first novel begins where Istanbul ends.

The novel recounts the mighty East-West encounter viewed from the intimacy of three generations of a bourgeois family much like Pamuk’s. It begins in 1905, just before the rise of the Young Turks and the end of the Ottoman Empire, then moving on to 1938 and the celebration of the Republic’s fifteenth anniversary. Atatürk dies and the clouds of WWII gather. The story ends in 1970 just before the military coup d’état strikes a blow at both the political left and the Islamists.

Cevdet bey, a rich and astute businessman, keeps out of politics. He’s a Muslim at a time when Armenians, Greeks and Jews dominate Istanbul commerce. The book may count 683 pages, but the three generations of the family parade before us at some speed, like photographs snapped at thirty-year intervals. In the chapter “Night and Life,” for instance, Cevdet, thirty-seven, wonders if he will be happy with his future spouse Nigân. She is the timid daughter of a Pasha who is devoted to the Sultan but near financial ruin and given to drink in the bargain. A few pages later Cevdet, now a grandfather, has lost his vigor, overshadowed by his sons Osman and Refik.

The placid Cevdet, appointed exclusive supplier of streetlights to the municipality, had also acquired the nickname of the Enlightener. This contrasted him to his brother Nusret, a passionate proponent of the French Revolution and another kind of Enlightenment. Likewise, Osman is rock-solid, whereas the restless Refik never knows satisfaction. Refik’s friends, like himself, are former engineering students at the university. Omer imagines himself a world-beater in the line of Balzac’s Rastignac, while Muhittin, ugly and long-faced, identifies with Baudelaire and vows to become a great poet or else commit suicide at thirty. Cevet’s nephew Ziya, also a bringer of municipal light, (but disliked by the family), forsakes illumination to become an army officer. (Given his choice of names, the author may have in mind the nationalist Ziya Gökalp.)

The novelist’s building blocks are the strong contrasts of temperament that mark the many characters. The narrative proceeds by dialogs, many of them interior and unspoken. Although few pages are devoted to Cevdet, his name graces the title and his exchanges with his brother and his father-in-law are the finest and most meaningful of the novel. All the author’s books to come exist in embryo in this first novel. Similarly, the novel’s first part determines how it will develop, one question always resonating, “Who am I and how should I live my life?” The theme will be worked out musically in infinite variation. Rhythmic repetitions of words and concepts emphasize the musicality (e.g., to be a Rastignac, to commit suicide, to fight over Hatay province). Characters reappear even after hundreds of pages (such as the unidentified Cenap Sorar who, referred to in a cited article of no importance on page 130, returns on page 613 as the second husband of one of the novel’s main characters).

The symphonic complexity of the story sends us back to its obvious model, Buddenbrooks of Thomas Mann. The Nishantashi quarter recalls Lubeck; the businessman Cevdet is like the businessman Johann; Refik nervously reading The Confessions of Rousseau suggests Thomas Buddenbrook seeking answers in Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation. But the similarities of the two books also serve to underline their fundamental difference: Mann’s novel recounts the decline of a family and a world, while Pamuk’s tells of a family, however tormented and dramatic, that is decidedly on the rise. The key word of the novel is nishan, “target.” Each character seeks to determine his own objective and so move forward. The word recurs throughout in different contexts, confirming Pamuk’s masterful control of his mother tongue. At this point translators must not opt for synonyms and a more facile flow of language for fear of scaring off readers. (Nor should publishers attempt to be reader friendly by neglecting to complete this historical novel with adequate notes.)

By law in 1934 Turks had to choose a surname. Muhittin chose Nishanci, because his father had been a “target shooter” in the army, a specialist rifleman. That explains Muhittin’s bitter remark when downhearted that he should instead have chosen Nishancioglu, “son of the target shooter,” seeing that he has no aim in life. Again, the successful or failed betrothals that involve so many of the characters recall that in Turkish an engagement ring is called “a target ring.” Finally, it should be noted that Cevdet’s villa, the novel’s sacred space and privileged location, lies in the Nishantashi quarter that translates as “target stone” because Ottoman soldiers went there, before it became residential, for target practice.

While not all the characters have found a target to aim at, the author is clear about his: He presses into service the great tradition of the European novel to search the soul of the rising Turkish middle class. Pamuk found inspiration not only in Thomas Mann but in nineteenth-century Russian writers. The frenetic political reunions that Muhittin frequents owe something to Dostoevsky’s The Possessed. Refik, the would-be reformer of the agricultural system, has much in common with Levin of Anna Karenina. (Refik is a Levin who failed.) Pamuk’s undertaking, moreover, has interesting parallels in the world of film. Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (1982) is a lengthy family saga in which the director revisits his own childhood. Woody Allen’s Love and Death (1975) is a wistful bow to War and Peace by way of parody. Like Allen and Bergman, Pamuk’s raw material comes from his own inner life, which he then fits into a preexisting model.

Pamuk’s way of proceeding is revealed in My Father’s Suitcase, his Stockholm speech of 2006 on receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature. A dialectic like that between Pamuk and his father occurs, modified by the needs of the novel, between Refik and Muhittin. And Pamuk is present in all the characters of the novel, but especially in Ahmet, Refik’s son, an aspirant painter who in 1970 reads the diary of his father without completely understanding it. Unlike Hanno Buddenbrook, however, who dies of typhus ending his dynasty, Orhan Pamuk, far from declining, rises. He closes himself in a room and sets to work.

Alias, the cultural supplement of the Roman newspaper Il Manifesto, published this article in Italian, May 14, 2011. Peter Byrne has translated and edited it.

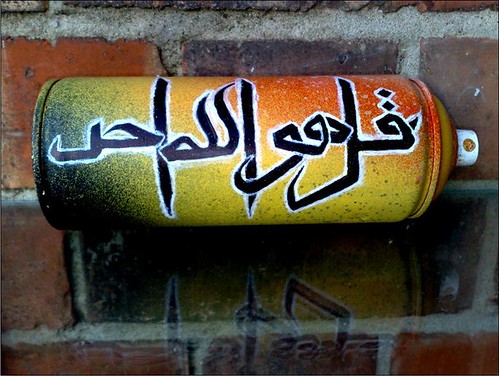

Say (O Muhammad (peace be upon him)): He is Allah, (the) One. Quraan 112:1. By Samee Panda.

Say (O Muhammad (peace be upon him)): He is Allah, (the) One. Quraan 112:1. By Samee Panda.

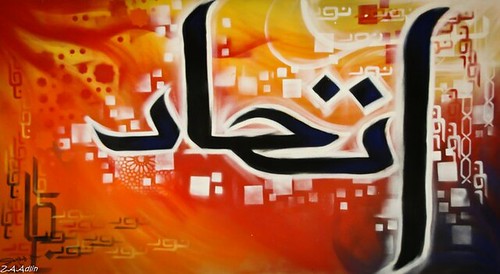

Itihaad (Unity), by Samee Panda. Graffiti done for Discover Islam Week @ De Montfort Uni, Leicester (aerosol on hardwood board).

Itihaad (Unity), by Samee Panda. Graffiti done for Discover Islam Week @ De Montfort Uni, Leicester (aerosol on hardwood board).

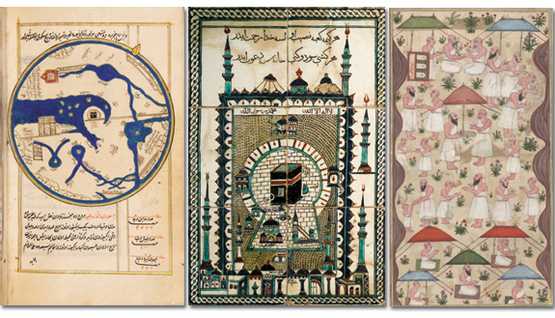

Tajdeed (Renewal), by hulya. Taken @ Istanbul. Exploring the concept of appreciating and holding the wisdom, lessons and essential structure of tradition, while soaking and reviving it with the colours of now. Renovation. Revival. Relevance.

Tajdeed (Renewal), by hulya. Taken @ Istanbul. Exploring the concept of appreciating and holding the wisdom, lessons and essential structure of tradition, while soaking and reviving it with the colours of now. Renovation. Revival. Relevance.

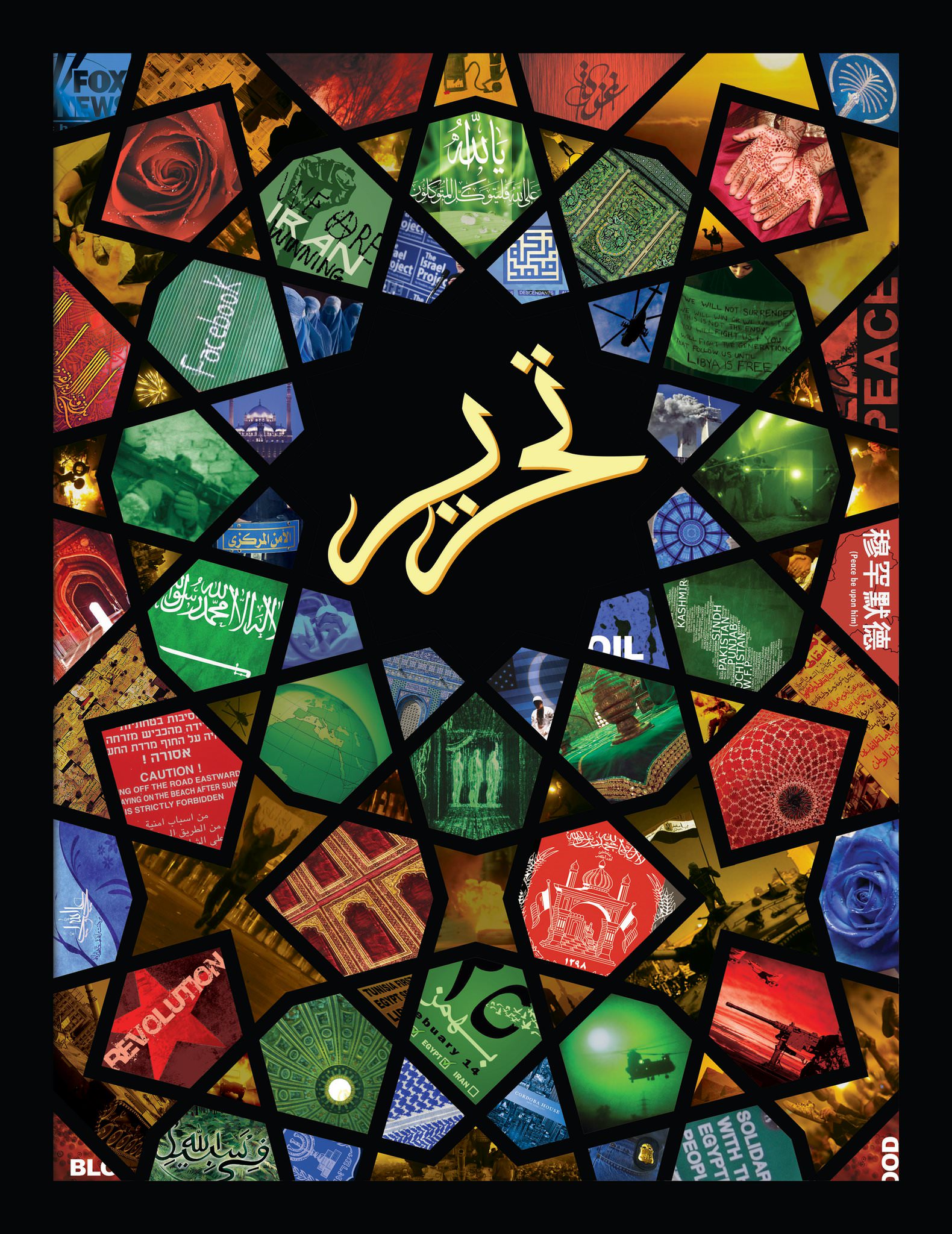

Collage, by Davi Barker

Collage, by Davi Barker