by Kathleen Seidel

Most coffee drinkers today are probably unaware of coffee’s heritage in the Sufi orders of southern Arabia. Members of the Shadhiliyya order are said to have spread coffee drinking throughout the Islamic world sometime between the 13th and 15th centuries CE. A Shadhiliyya shaykh was introduced to coffee drinking in Ethiopia where the native highland bush, its fruit and the beverage made from it were known as bun. Many believed this Sufi was Abu’l Hasan ‘Ali ibn Umar who resided for a time at the court of Sadaddin II, a sultan of southern Ethiopia. ‘Ali ibn Umar subsequently returned to Yemen with the knowledge the berries were not only edible, but they also promoted wakefulness. To this day, the shaykh is regarded as the patron saint of coffee growers, coffeehouse proprietors and coffee drinkers; in Algeria, coffee is sometimes called shadhiliyye in his honour.

The beverage became known as qahwa – a term formerly applied to wine – and ultimately to Europeans as “The Wine of Islam.” It became popular among the Sufis to boil up the grounds and drink the brew to help them stay awake during their night dhikr. (Roasting the beans was a later improvement developed by the Persians.) Coffee drinkers even coined their own term for the euphoria it produced: marqaha.

The mystic theologian Shaikh ibn Isma’il Ba Alawi of Al-Shihr stated that when imbibed with prayerful intent and devotion, coffee could lead to the experience of qahwa ma’nawiyya (“the ideal qahwa”) and qahwat al-Sufiyya, interchangeable terms defined as “the enjoyment which the people of God feel in beholding the hidden mysteries and attaining the wonderful disclosures and the great revelations.”

It soon became apparent coffee’s benefits could be extended to the workday and the local economy as well. The southern Arabian climate was ideal for coffee cultivation and the ports of Yemen, particularly the port of Mocha, became the world’s primary exporters of coffee.Coffee’s use spread to Mecca where, according to an early Arab historian, it was drunk in the sacred mosque itself so that there was scarcely a dhikr or mawlid where coffee was not present. Coffee spread throughout the Islamic world by way of pilgrims, traders, students and travellers. Al-Azhar became an early centre of coffee drinking and a certain amount of ceremony began to surround it.

Over time, coffee even acquired an angelic reputation. According to one Persian legend, it was first served to a sleepy Muhammad by the Angel Gabriel. In another story, King Solomon was said to have entered a town whose inhabitants were suffering a mysterious disease; on Gabriel’s command, he prepared a brew of roasted coffee beans and thereby cured the townspeople.

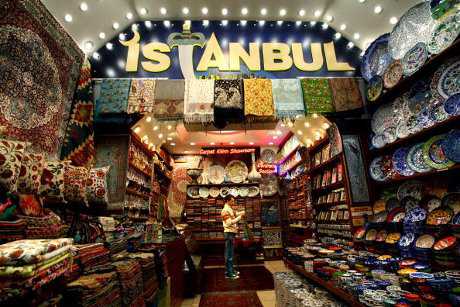

By the early 16th century CE, coffee drinking moved to the secular sphere and a new institution evolved that transformed social life throughout the Islamic world. And coffeehouses supplied more than beans; they had the expertise to prepare the brew, the necessary equipment and a convivial milieu in which to enjoy it. Ahmet Pasha, the governor of Egypt during the late 16th century CE, actually built coffeehouses as a public works project, garnering him great political popularity. In the mid-17th century, two Syrian businessmen, Hakm and Shams, introduced coffee to Istanbul, established the city’s first coffeehouses, made a fortune in the process and established a new and profitable arena of economic activity. Evliya Efendi wrote of the coffee-merchants of Constantinople: “The Merchants of coffee are three hundred men and shops. They are great and rich merchants, protected by Shaikh Shadhili… ”

Throughout the first few centuries of its history in the Islamic world, coffee’s popularity engendered great controversy. Many were suspicious of the effects of caffeine and the gatherings in which it was consumed – they seemed debauched to some and subversive to others. Coffeehouses competed with mosques for attendance and as unsupervised gathering places for wits and learned men, provided spawning grounds for sedition. The wags of Istanbul jokingly called the coffeehouses mekteb-i ‘irfan, “schools of knowledge.” Efforts were launched and persisted for at least a hundred years to declare coffee an intoxicant forbidden by Islamic law.

During Ramadan in 1539 CE, Cairo’s coffeehouses were raided and closed, although only for a few days. Soon after coffeehouses achieved popularity in Constantinople, Sultan Murat IV closed them all and they were to remain dark until the last part of the century. But as soon as the Sultan’s edict went into effect, the coffeehouse patrons, their money and their social life went elsewhere: “In Brussa there are 75 coffeehouses frequented by the most elegant and learned of the inhabitants. All coffeehouses, particularly those near the great mosque, abound with men skilled in a thousand arts…” writes Efendi.

Opposed by well-educated coffee-drinkers from the highest ranks of the religious and political hierarchy, who did not look fondly upon innovative, legal prohibitions, the moralists fought a losing battle. The “tavern without wine” offered a respectable gathering place for men to socialize and entertain away from home and business was especially brisk during Ramadan when proprietors made extra efforts to draw crowds with storytellers and puppet shows.

Despite coffee’s eventual secularization, the fondness for it in Sufi circles and the motives for its use were not lost. Helveti dervishes were among those who enthusiastically drank coffee to promote the stamina needed for extended dhikr ceremonies and retreats. Once coffee was readily available throughout the Ottoman Empire, it became a fixture of daily life in the Helveti dergahs.

In Persia, coffeehouses evolved into hotbeds of lasciviousness and political dispute soon after they were introduced. Shah Abbas I responded to this situation by installing a mullah in the leading Isfahan establishment; he would arrive early in the morning, hold forth on topics of religion, history, law and poetry and then encourage those assembled there to be off to their work. A pious ambience was thereby promoted, an example was set for other coffeehouses and a potentially volatile social milieu was somewhat controlled. Poets and mystics occasionally took up permanent residence; for example, Molla Ghorur of Shiraz settled in Isfahan in his old age and established himself at a coffeehouse, which soon became a gathering place for those seeking spiritual guidance.

By the end of the century, coffee was fashionable throughout Europe and its cultivation and use subsequently spread to North and South America. Wherever it has been introduced, it has become a symbol of hospitality and a vehicle of sociability. The current resurgence in popularity of the coffeehouse is undoubtedly a response to the marketing efforts of coffee producers and enterprising restaurateurs. It may also contain a longing for the sort of companionship the Shadhiliyya dervishes enjoyed 600-years-ago, as they gathered to remember Allah and passed the cup from hand to hand.

—

Adapted from Serving the Guest: A Sufi Cookbook by Kathleen Seidel © 1999, 2000. Visit the Rumi Rose Garden Cafe & Market, 3660 E. Hastings St., Vancouver, 604-558-4455. www.rumirose.com