RÉMI BOURGEOT: CAN TURKEY DO WITHOUT EUROPE?

One of the available explanations accounting for recent Turkish performance would supposedly be Turkey’s distancing itself from Europe and gaining alternative markets, especially in the Middle East. Rémi Bourgeot, an economist expert on emerging countries, thus tackled the theme of the Turkish economy’s progressive “orientalisation”.

Indeed, there would be no point in denying that Europe’s crisis could hamper the development of Turkey/EU economic relations. Turkey’s attempts to explore alternatives to European demands are legitimate in such a depressing context. In the last 10 years, the Middle East rose from approximately 10 to 20% share in Turkish external trade. Yet, talking about “orientalisation” does not really make sense. The EU still accounts for half of Turkey’s exports, around 40% of its imports and half of FDIs directed to Turkey come from Europe. Besides, Turkish trade with the Middle East is not of the same nature as Turkey/EU economic ties: it is not composed of the same type of products and comes from different regions. Turkey’s North, with the industrial region of Bursa, essentially produces industrialized goods that are exported towards Europe. Turkey’s South, mostly around Gaziantep, is specialized in low-technology products like cement and exports to the Middle East, especially Iraq.

Hence we are not talking about the same structures and there is no substitution between one and the other; they can at best be complementary.

The idea of an “orientalisation” of Turkey’s economy has also been supported by the AKP’s Middle Eastern diplomatic moves and policies, notably the visa lifting and the Free Trade Agreements (FTA) signed with Syria, Iran, Iraq… There was even a discourse on economic integration à l’européenne: Erdoğan brought up the idea of a “Şamgen” union, in reference to the Shengen zone (Şam meaning Damascus). Yet such prospects seem to be rather far-fetched given the economic disparity and the diversity of political regimes in the region, not to mention the high current political tensions.

In fact, energy is the most important factor driving Turkey’s relations with its non-European neighbors. The “zero problem” policy was notably aimed at pacifying relations with energy-provider countries so that Turkey can trade more easily with them. In order to reduce the energy burden (which weights a lot on the current account deficit), Turkey tried to export its middle-technology goods: textile, construction… to countries that were important energy producers and financially solvent. In geopolitical terms, one of the objectives of Turkey’s Foreign Policy is to position itself as a regional hub. Located between the main energy resources (Russia, Central Asia, the Middle East), Turkey shares the same essential goal as its neighbors: transporting energy to Europe via Turkey. At the end of the day, the paradoxical outcome of this hub strategy is that it might turn Turkey even more dependent on European demand.

Can Turkey be considered as an economic success story?

Thanks to a closed economy, major Turkish companies emerged and were able to compete internationally when the economy was opened in the 1980s. Today, Turkey’s economy is dominated by the private-sector, with main conglomerates leading the way. Ünal noted how the most important groups, gathered in TÜSIAD (Turkish Industrialists’ and Businessmen’s Association, Türk Sanayicileri ve İşadamları Derneği) provide a model not only in terms of economic development but also to encourage women’s labor (TÜSIAD’s current president, like its predecessor, is a woman). Nevertheless, if Turkey has succeeded in becoming a medium-technology economy, more needs to be done to acceed the next level. The reform agenda should be pursued seriously if Turkey wants to keep growing.

Can we forecast the emergence of national şampiyons (champions) with the rise of Turkish FDI abroad?

Çağlar warned against lacks in the economic environment that could prevent Turkey’s main companies to produce sophisticated goods and grow worldwide. A bad performing tax system, informal activity, bureaucracy are still blocking economic development in Turkey. A major leap in the conception and implementation of economic policies is still needed in order to support Turkish companies on the international level.

As far as investment abroad is concerned, even though there are some successes (Gründig bought by Beko, Godiva acquired by Yıldız Holding…), there is a also need of a real investment policy. At the moment, the only large scale investment program abroad is about rebuilding ancient ottoman mosques and houses.

Whither Turkey’s economic relations with the Middle East?

The economy is now being used by the AKP as an instrument of foreign policy. Turkey has become a major economic power in Iraq; Economic sanctions were recently announced against Syria (even though they will apply to small trade quantities), and the relationship with Iran is essential to secure Turkey’s energy needs. In fact Turkey is very keen on engaging economically with Iran, as it can help lowering its dependency on Russian gas (which amounts to more than 60% of Turkish gas imports). Yet, significant challenges lie ahead. The lack of energy is a major disadvantage for Turkey and the recent upheavals in the Arab world cast uncertainty to the prospect of energy transportation from the Middle East to Europe via Turkey. The Kurdish issue could also be a destabilizing factor both at the internal and external level.

Does the Prime Minister manage economic policy alone, or does he rely on a broader team of decision makers?

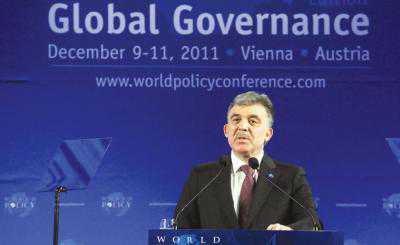

One has to stress that Prime Minister Erdoğan is not the only leading figure in the AKP. President Abdullah Gül is also a prominent personality who could also take responsibilities should the necessity arise, as already happened in the past (Gül was briefly Prime Minister in 2002, when Erdoğan was temporarily impeached to do politics). The AKP’s economic policies have been relatively pragmatic so far, but it remains to be seen if the party will stick to its reform agenda, which was apparently left apart over the last years.

Does Turkey compete economically with France?

Politics affect negatively Turkish-French economic relations. President Sarkozy’s decision to block Turkey’s EU membership bid and France’s position on the Armenian genocide have in certain cases excluded French companies from call for tenders in Turkey. Furthermore, in regions like the Caucasus, Central Asia and especially in Africa, Turkish companies are gaining economic grounds, sometimes at the expense of French companies. Nevertheless, France is an old-time economic partner of Turkey and one of the main investors in the country the Renault-Oyak partnership is one example among many. The two economies complement each other: France and Turkey can thus be partners in terms of high technology products and compete as far as low and middle-technology products are concerned.

© copyright StarAfrica.com