24. November 2014

NEW SOUTH WALES PARLIAMENT

AUSTRALIA

I would like to acknowledge the Gadigal people of the Eora nation, who are the traditional custodians of this land on which we are gathered. I would also like to pay my respect to the elders past and present of the Eora nation and extend that respect to other Aboriginal people present.

I would also like to acknowledge, the presence of the Members of Parliament here with us, and other distinguished guests.

I would also like to thank the New South Wales Parliament and the Parliamentary Friends of Turkey for inviting me to speak in this parliament.

This is my first time here in Australia. Upon arrival yesterday, I heard some stories about sharks. Considering the media here, I imagined how interesting it would be for a headline to read “Genocide denier attacks shark,” and in the story the “genocide denier” would be quoted as saying “what shark?”

WAS IT A GENOCIDE?

Well, was it a genocide? Why is this even asked? Why do people want to characterize an event without having to study what happened… a century ago? And – how about this for a preliminary question – what is genocide?

Genocide is a characterization of an event. Genocide is not the event itself. It is an epithet, not a name of an event. It is a legal characterization given to an event if the event falls within the meaning of the term as defined in the Convention adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 9, 1948.

According to Article 2, genocide means an act committed with “intent to destroy,” and the group that is being destroyed is either national, ethnical, racial or religious, and is destroyed as such. That’s what it says. Notice the “as such.” Notice that “political” is not mentioned as a group identifier. The victims of a response to a rebellion are not victims of genocide, no matter what. If you do not want your wife, your husband, your child or your next door neighbour to be burdened by your own act of rebelliousness, then the time to think of it is before committing an act of rebelliousness against the state. The intent on the part of the state in cases of a reaction to rebellion is to maintain sovereignty, not to destroy a group of people. Remove the political condition of rebellion, and you shall also remove whatever state aggression happens as a result. No rebellion, no deportations, no massacres. The rebelling group, though it may have a national, ethnical, racial, or religious identity, is a political group once its purpose is to replace the sovereign, once its intent is to destroy the state in its current existence. In the Armenian case in World War One, the Armenian leadership was leading a rebellion under the intention – shared by its sponsors, the Entente – to destroy the Ottoman state. The Ottoman state, was not trying to destroy the Armenian people – and it is a fact that many Armenians in Anatolia were left unharmed – rather, the Ottoman state was trying to save itself, and to survive as a sovereign.

Considering the weight of the legal characterization that is genocide, a responsible person would not use genocide as a name, unless it was legally determined to be genocide, and Article 6 of the Convention states that persons charged with genocide “shall be tried by a competent tribunal of the State in the territory of which the act was committed, or by such international penal tribunal as may have jurisdiction with respect to those Contracting Parties which shall have accepted its jurisdiction.” These are exact words, and they mean that only suitable courts may charge a person with genocide. Neither of the types of tribunals stated in the article have ever declared that what happened to the Armenians in 1915-16 was genocide, that’s one point. Another point is that persons are to be charged with genocide, not a nation. The third point is that if you look at the wording you see that there was a clear forward-view to the term genocide. Meaning, it was designed to prevent future – future – genocides, and that’s the “shall” part. “Shall” has a clear tense-distinction. Future. That was the idea that was put to paper. Genocide was something to be prevented from happening in the future. It was not designed to become a source for a disingenuous discourse that consists of false accusations about the past.

WHOSE FAN ARE YOU?

Now that we have a decent grasp of what genocide is by definition, let us consider the difficulty of characterizing an event in general. It could be any event. There is a difference between facts that make an event and the characterization of the event. We might be looking at the same thing and characterize it differently. It happens in sports regularly. In soccer. I am from Israel, and in Israel to this day, the thought of Australia brings to mind one name: Charlie Yankos. People know him here? Charlie Yankos? Well that name still keeps many Israelis up at night. You’d think there’d be other names to keep Israelis up at night, but no. It’s Charlie Yankos. Israel and Australia used to tangle in the 1980s in the World Cup qualifiers. So, in soccer – it’s a game, it’s a sport, right – say there is a semblance of contact in the penalty box, a possibility of a foul, i.e., an event: do you think both sets of fans are going to characterize the event in the same way? No! They’ll see the same thing, but characterize it differently.

But that is what historiography does, it characterizes events according to the needs of collective memory, to strengthen group solidarity. The characterization of the event informs us on whose fan you are, than it does on what happened. So whose fan are YOU? Are you a fan in this political game in which only Armenians and Turks are on the field? Who runs this game? Do you want to be the referee? As the referee you’d have the players of both teams begging that you characterize events in a certain way. You don’t see players asking the referee “hey, why are we even playing this game?” They are so caught up in the game. Being the referee in that particular situation is a position of power, as the players of the two teams hold their breaths, waiting for the referee to decide how to characterize what happened. Referees would like to freeze this moment of getting attention, before actually making a decision that will disappoint one of the two sides. Such is the issue between the Armenians and the Turks. For some reason – which is not that big of a mystery if you come to think of it – the referee, or referees are suspending the decision. It might be clear that there was contact but no foul, but the important aspect of this event and its characterization has become this frozen moment in which Turks are shown as having to plead with the referee that there was no foul. It is a humiliating position to be in, if you are the Turks. It is frustrating for the Armenians, who for a long time think that they are about to get a penalty-kick. They’re not going to get it. And let me tell you something important: there are no real referees in the international political system. But a great power, or an aspiring power, would like to be thought of as a referee. Referees are the most powerful when there is a situation in the penalty box. Imagine a referee that was able to delay the decision, and just bask in the moment. Isn’t that a referee’s fantasy, the best of both worlds: to have both teams beg for a favorable decision, and yet not have to make a decision on the characterization of the event. In the game between Armenia and Turkey there are no real referees, there are people who pretend to be referees, but they are actually extensions of whoever is running the game – and they want to freeze this moment, to keep this question of foul contact in the penalty box as long as possible – the most dramatic state of the game on pause – so that the Turkish team will constantly appear as running to the referee in “denial” of having committed a foul. This image of denying that something happened is the whole point, and it has a life of its own, regardless of whether there was a foul in the penalty box. The Turks are constantly shown as saying “no” to something, like the players who run at the referee to say, “no, no penalty.” A century after the contact in the box. The Turks are constantly shown as if they are denying that something happened.

DENYING A FACT OR REFUTING A CHARACTERIZATION?

Let’s talk about real denial. Holocaust denial – denial – is something completely different. To say, for instance, that there were no gas chambers in Auschwitz is to deny a fact. To say that Jews were not executed by gas chambers, is to say that an event did not happen. In our soccer analogy, to say that the players weren’t even in the box would be a denial of fact, while to say that the contact in the box does not qualify as a foul is to refute a characterization of an event. One denies facts. If something is not a fact, then it is not denied, it’s refuted or rejected. People might call you a denier to make it seem as if they have ownership of facts. It is a tactic. It is my understanding that the Turkish government recognizes the contact in the penalty box; it recognizes every aspect of the Armenian suffering in 1915-16, but it rejects the biased characterization of the event. The fact that those who accuse Turkey of genocide and denial are ignoring Turkey’s clear position, and ignore the distinction made between fact and its characterization, should serve as a strong indication that there is a political commitment at play to press this issue against the Turks regardless of facts. A genuine study is that of facts. To study the actual contact first, before deciding how to characterize the events.

Those who study the facts full-time, are the very opposite of deniers of facts. Justin McCarthy was here in Australia and he was accused of terrible things. This Dr. McCarthy, whom I have had the pleasure to meet once at a conference in Sarajevo, is not a denier of facts. He is dedicated, as a scholar, to knowing more about what happened. This impressive man, a walking encyclopedia of a man, has spent a lifetime of studying the facts of the events and surrounding the events. I sit and study facts all day. This is what I do. I am not a big-time barrister in London, I am not even a recording artist. This is not a gig for me. I am committed to studying facts. I am finding them. Give me time, and these facts will become known. Give me a platform, and these facts will become known. Would you publish my work here? Do you want to know what happened, or have you already decided to take part in running this political game?

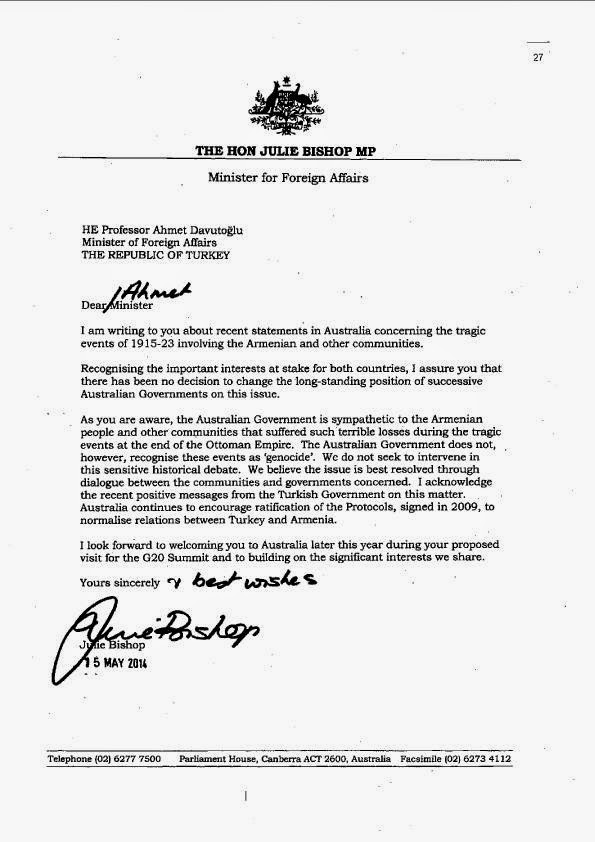

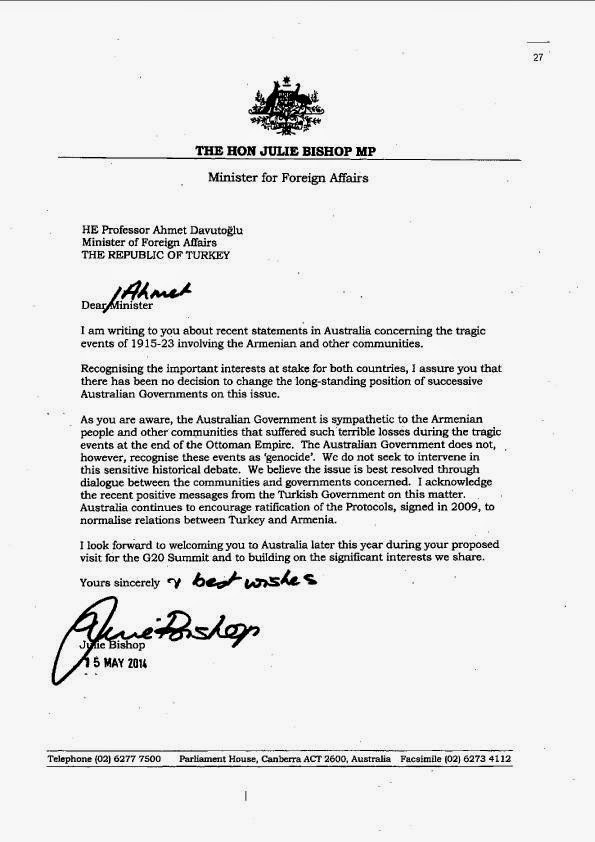

THE LETTER BY FM JULIE BISHOP

Even a well-articulated letter such as that drafted by the Honourable Julie Bishop in June – stating that the tragic events are not characterized by the Australian government as genocide – even such a letter only extends the game if it is accompanied by efforts of other branches of the Australian government to utilize the media and education to indirectly promote the belief that the event should be characterized as genocide. It is clear to me that by making the public believe that it was genocide, great pressure is placed on the Turkish government, and then the Western governments reap the benefits of this pressure, and letters such as the one by the Australian Minister of Foreign Affairs are considered a favor to Turkey, to which a price is attached. It is like a coupon that Turkey is expected to accept. However, the jig is up on this type of double play.

POLITICAL POWER

Why is it so easy for scholars who are not Ottomanists to publish work that is readily accessible to a wide audience in the US, in the UK, and here in Australia? Why is it so easy to publish a book in which truly skilled scholars such as Dr. McCarthy are disrespected? Why is it so easy to call Turks genocidal? To accuse an entire nation of something so abominable without the expertise, without the knowledge of Ottoman history and language?

Samantha Power, now representing the United States as its ambassador to New York, she did this. There was power behind this book of hers. Infrastructure. Typically, books that are filled with inaccuracies – the work of shoddy research – are not expected to win prizes. This book won the Pulitzer Prize. No joke. It presented “Turks” as perpetrators of a terrible crime in a matter-of-fact way, used imprecise descriptions, citing fiction as fact, advocating a distinctly anti-Turkish view of history.

Samantha Power is a political actor. Look at what she said about Russia in the book and what she has to say about Russia now. Her opinion changes according to the political needs of the United States government. Period. So yeah, she did it, she freely tarnished the image of an entire nation without being able to cite Ottoman sources, by simply and unabashedly relying on English writings of Anglo-American political actors. Also, Michael Ignatieff, a famous friend of hers, almost the Canadian prime-minister, did it. Michael Oren, another famous friend of hers, the former American-turned-Israeli ambassador to the United States, he did it. These people are not Ottomanists, and, judging by who they cite, they did not spend any time studying first hand facts on Ottoman history and language. They are famous Harvard scholars and political actors, who have access to readers, and influence public opinion. They do not seem to want to access facts. They have access to readers, to the public. Power. And they use this power to make terrible accusations against Turks in general, that they are genocidal and deniers. Have these scholars no shame? Do we know why people who do not know what happened – and do not want to know what happened – are pretending to know what happened and are clearly popularizing a phrase that combines “Armenian” with “genocide” as if a name? It makes you want to ask “What’s going on?”

POLITICAL PURPOSE

Here’s what’s going on. The accusation of genocide serves political purpose. Three main purposes, one that is great-power specific, one that is Turkish-specific, and one that is Armenian-specific.

The first one, it allows great powers, usually the United States, to replace disfavored regimes in an indirect manner. Instead of just using sheer force to dominate a region, which also happens, it is more advantageous for a great power to do so by setting up a revolt that would lead to a reaction by the sovereign, that would lead to international acceptance of an intervention led by the very same great power that concocted this mess. This way, the sovereign gets the blame for killing its own people, and the great power, typically America, typically if you have oil or other important resources, gets to show up and save the day, as Samantha Power would have it do. Interestingly, the definition of genocide as it was drawn up does not consider political groups to be victims of genocide. Meaning, if a great power wants to stage a genocide in order to topple a regime, then it will have to make it seem as if the group of people is persecuted for religious or ethnic reasons. Other times, the great power just doesn’t care. This happens when the popular perception is all that the great power cares to affect, without having to admit that it is misusing the term in the legal sense. For instance, in oil-filled Libya, those were clearly political rebels who were facing annihilation by [Muammar] Gaddafi, and yet that did not stop President Barack Obama from using the phrase genocide in justifying the planned intervention. By the way, at the time, Power was a member of Obama’s National Security Council. Another point of interest regarding how great powers use the genocide concept is that the Genocide Convention gives no heed to the fact that many massacres are the result of the intent to instigate by a third party to the conflict. It has been common to point a finger at third parties who did not stop massacres, suggesting that they were complicit. However, there is not much discussion in academia on how the Genocide Convention sets free third-party instigators for whom it serves a political interest to encourage a rebellion, even when the terrible consequences are anticipated. In this instance, the great power mobilizes a group within a state to rebel and attempt to replace the sovereign; then, either the rebellion succeeds and the great power achieves a moment of success in its foreign policy, or the rebellion fails and then the sovereign state that quelled the rebellion is blamed for the atrocities of war. This is not genocide, this is sophisticated imperialism.

The second purpose, the Turkish-specific aspect of the accusation is that it provides the United States and the West with a political tool, a “stick” to raise against Turkey, to press it to make policy decisions according to their wishes, to deny Turkey its place in the European Union, to weaken its image and influence. The lack of a perfect cultural affinity between the US and Turkey has meant that there is no such brotherhood as that which exists among the English speaking countries. Applying for a visa to come here, it was interesting to learn that the information collected as part of my application is to be shared with government agencies in the US, the UK and Canada, the English-speaking gang. Turkey was not one of them. There is no complete trust in Turkey. Turkey’s different. However, if you are the United States, you are thinking that there has to be a way to make sure Turkey always picks up the phone when America calls. Sure, there have been carrots in this relationship. Turkey has done very well since the 1950s thanks to cooperation with the United States. But it’s doing much better now, some might say that things have been going too well for Turkey. Its government has reached a level of stability to the point where measures have finally been taken to reduce the influence of outside entities in Turkey. This is a problem for those who thrive on having outside influence around the world. It means that the Turkish government is vilified on Western TV whenever it has to take bold steps to maintain its democracy through fighting outside interference. It is not necessarily that there are better and lesser democracies, but rather sometimes some democracies face more challenges than others. As Turkey is strong enough to face new challenges it has not faced before, this also means that from the West’s perspective there is a need for means to influence Turkey’s decisions. Hence, the Armenian issue.

Three, the Armenian-specific purpose of the genocide accusation is that it distracts from a real ongoing grievance, and that is the Armenian occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh. As long as the headlines on the Armenians in the West show them as victims, there is not enough oxygen in the public’s brain to think of them as aggressive occupiers. The Armenian-Azeri conflict is an explosive conflict that has ignited the popularization of the genocide accusation as a proxy-polemic, almost like a replacement-conflict. As long as Nagorno-Karabakh is occupied, Armenian memory will be politicized, and the Armenian people will continue to suffer from this ill-advised politicization of Armenian memory. Instead of better understanding their own past, instead of enjoying greater international relations in their present, the Armenians are locked out of acting toward a more prosperous future for Armenia. It is a simple formula: settle the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh, and the proxy-polemic would fade away, the misuse of genocide will stop. Granted, the genocide accusation began before the occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh, but the two other purposes have already began to lose their momentum.

STUDYING “THE STUDY OF GENOCIDE”

There is so much material to be studied – on the British political actors in the late nineteenth century, on the Anglo-American imperialist cooperation leading up to the twentieth century, and on the emergence of genocide as a field of study in the last two-three decades – that over time this information will be revealed and undoubtedly expose the political designs of this genocide accusation against Turkey. There is so much interesting material that there ought to be an association of scholars that are studying the study of genocide, studying the people behind the organization of genocide study: how did this field of genocide study, this genocide study, come into being and why. Study all of these people who made ungrounded accusations against Turkey, name by name, one by one. It is an utter disgrace to accuse an entire people of genocide without caring to study the facts. Why has it been so easy to issue such accusations against the Turkish people? What aspects of prejudice are related to this? Racism? Islamophobia? Racism and Islamophobia not necessarily as the reasons why this accusation is made – the reasons for that are political, as I stated – but racism and Islamophobia may explain why it is so easy in the West to make the accusation and have it be so effective in convincing the public of Turkish wrong-doing.

“CREDIBLE INDEPENDENT EXPERTS”

To me, it is an academic priority to understand what such people have done in the name of academia. How political interest has disguised itself as academia. It is already a fact that Cass Sunstein, who happens to be Samantha Power’s husband, and a friend of the US president, pushed for the US government to use scholars for its own interests. On the same year of being appointed the Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs – a lofty US government position of information control – he co-authored an article in support of government involvement in academic affairs if it helps the government: “The government can partially circumvent these problems [referring to accusations of conspiracy against the US government] if it enlists credible independent experts… There is a tradeoff between credibility and control, however. The price of credibility is that the government cannot be seen to control the independent experts.” This is in the Journal of Political Philosophy, volume 17, issue number 2, 2009, page 223.

This begs an immediate question that should be asked more and more: How much of this genocide accusation is done by the US government? How much of this academic discussion is really a manifestation of political power? It is important to remember that the term genocide became international law because of power, not morality. Morality is owned by power. The US itself was the driving force behind the convention but it did not sign the ratification of the Genocide Convention until the 1980s. Why? Because it feared that there would be accusations made against what happened to the Native Americans and the African slaves. The American enterprise that is known as the International Association of Genocide Scholars took care of that problem. Out of 20 issues of Genocide Studies International by the IAGS, upon its thousands of pages, only 9 pages of one pathetic article discuss the Native Americans. The verdict, surprise surprise, is that it was not a genocide per se. And that was that. When you have power, you control the conversation, and then you control the content, you control the language, you control what people think, and then you can talk about freedom. Freedom is not a problem for the government that has enough power to control thought. Do you know who thought the Native Americans suffered a genocide plain and simple? Raphael Lemkin.

RAFAEL LEMKIN

Let’s talk a bit about Raphael Lemkin. When the term genocide first became published in a 1944 book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, under Lemkin’s name, he was employed by the United States government.

The book has the marking of having more than one author, and it is questionable, in my view, that Lemkin even wrote it, considering the quality of the English and the fact that he had only made it to the US in 1941 for the first time. There was no American TV to influence foreigners’ English at the time. There was no Bonanza or MacGyver on Eastern European TV in the 1930s. He could not have written that book on his own, and yet he does not credit anyone for either translating it or editing it, not even proofreading it. It’s odd. It is even odder considering that in the late 1950s when he was no longer employed by the US government, his autobiography was dismissed by publishers in the US partly because of his poor grammar. This was a problem 15 plus years after he immigrated, but it was not a problem just two-three years after he immigrated to the US? That is really odd. The only way for this to make sense is if he didn’t really write the 1944 book, and, guess what, he was working for the US government at the time, when a whole bunch of ivy-league graduates could do it for him.

Regardless of who actually wrote the book, it coins genocide without regard to the Armenians. It does not mention Armenians, not even once. And yet, Yair Auron, an Israeli scholar who is affiliated with the Zoryan Institute – that’s an institute that promotes Armenian affairs in academia – is quoted all over the internet as saying “When Raphael Lemkin coined the word genocide in 1944 he cited the annihilation of Armenians as a seminal example of genocide.” That is not even a half-truth, but an entirely false statement. Why is this scholar saying such a thing if it is not true? Auron only began to write profusely about the Armenian issue in the 1990s, 15 years after completing a doctoral dissertation on a completely different topic, on Jewish youths in France… he might as well be a barrister. And he still goes on TV shows in Israel, writes for Haaretz from time to time, unopposed, without anybody questioning the veracity of his statements. Notice that I am not calling him names, like is done by such people who call Dr. McCarthy a denier; notice that I am not degrading Auron just because he doesn’t agree with my opinion. I am pointing out an actual statement made by him that is completely false.

This Dr. Auron has been active in facilitating the teaching of the Armenian case as genocide in Israel, holding a position of influence in the main college in Israel that educates the teachers of tomorrow. There are organizations that frame people’s understanding of history in anti-Turkish ways. An “international educational” organization such as Facing History and Ourselves is said to reach over 1.5 million school kids, through close to 20,000 educators in the US and Switzerland. No wonder, then, that in Switzerland they believe these stories about World War One and Lemkin. A false narrative has made it seem as if Lemkin was inspired by the Armenian suffering to coin genocide. Is it any wonder, then, that when the honourable judges of the European Court of Human Rights corrected the wrong done by the Swiss government and courts that convicted a Turk, Doğu Perinçek, for sticking to his understanding of what happened, even these honourable judges who made this correction, still said, and this is a quote “We know that when Raphael Lemkin (Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, 1944) coined the term genocide, he had in mind the 1915 massacres and deportations” (that’s on page 53 of the English version of their decision)? No, we do not know that. In fact, Lemkin did not express any thought on the Armenians at that time. This falsehood is easily acceptable for reasons that must be examined.

The truth is that while he was employed by the US government, the Armenian issue did not seem to be on Lemkin’s mind. Why would it be? It was not a US political agenda at the time. After Lemkin was dropped by the government, he wanted to promote the term in every way he could, and promote himself in the process, and he became involved with the activities of American Christian organizations, who already had a long history of involvement in the tensions between Armenians and Muslims. Under their influence he said in an interview to CBS in 1949 – one of these organizations may have arranged for that interview, by the way – that he became interested in genocide because of what happened to the Armenians. However, at a different time, while campaigning for genocide ratification in Italy, and being asked “When did you first become interested in Genocide?” his answer was Armenian-free, made to fit to his audience in Italy. Time and place, audience and purpose, determined his answers. His written autobiography was just as flexible. And yet it is his autobiography, the one that could not get published while he was alive, that Samantha Power cites in her book like it was a mathematical truth.

At the twilight of his life, while his push for greater discussion on genocide and for Noble Peace Prize nominations was ongoing, Lemkin referred to a total of 62 cases in history – in Antiquity, the Middle-Ages, and Modernity – as genocide. Among them the genocide of Native Americans, he called it the “Genocide against the American Indians,” the genocide by the Greeks against the Turks, the genocide in Belgian Congo. Of the 41 cases in modern times, number 39 states “Armenians.” Number 41 was added in handwriting and says “Natives of Australia.” This does not mean that they were all genocides. These were all researched hurriedly and superficially to gather as many cases for the promotion of the term’s popularity. Not only was the historical research insufficient, over time Lemkin distanced his definition from that of the Genocide Convention and began to follow a home-made definition of genocide. But, what’s interesting is that out of all of these, for some reason – and what is that reason? – the Armenian case, or should I say the anti-Turkish case, is the one that is kept alive, and made into an ongoing and going and going – without being gone – issue. Certainly not forgotten, but falsely advertised as such.

JAMES BRYCE AT THE CENTER OF THE FALSEHOODS

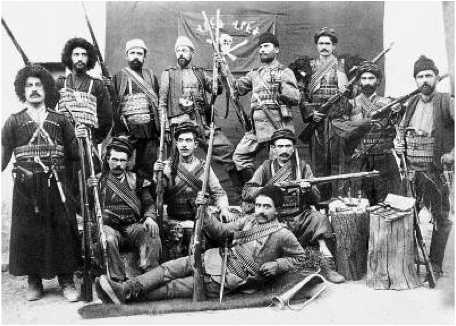

This accusation of genocide may still be turned around from falsehoods to greater truths that have yet to be brought out. But first we must expose the falsehoods for what they are. What are the genocide claims based on? Wartime articles in the New York Times? Missionary accounts? Armenian memories written down in Massachusetts? The report by Ambassador Henry Morgenthau whose embassy functioned as a hub for Entente agenda during the war’s first couple of years? The British government-based, government-issued, Blue Book?

Go to the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, Special Collections, seek the help of a nice gentleman by the name of Colin Harris, and you will find there the catalogue of papers of one James Bryce.

Going by my own growing familiarity with the facts, what happened may be characterized as a tragedy because the Armenians were set up for a big painful fall by the British, and by presumptive Armenian leaders, the so-called Armenian representatives who met with British officials – headed by Bryce – in London hotels, and acted irresponsibly toward the many innocent Armenians who were – as a result – fated to suffer the consequences of the actions of these so-called Armenian representatives.

These representatives were fed by British hubris as they strove to advance the political quest for an Armenian independent state on Ottoman land, their personal ambition to be leaders of this state, but mainly on behalf of British imperialist agenda. There is no question that these actions, namely colluding with the British and agreeing to lead an intensified rebellion, meant selling out the safety of the Armenian people in eastern Anatolia who were not the majority in any of the provinces there, and would be subject to an escalation in violence similar to what followed Bryce’s previous campaigns to excite Armenian rebellion in the 1890s.

James Bryce is not just the man behind the Blue Book during World War One. In 1967, Arnold J. Toynbee, who during World War One was a young historian fully employed by the British government to work under Bryce in editing the Blue Book and manufacture other propaganda, admitted that the Blue Book was designed to affect the American public during the war. By World War One, Bryce had already established strong connections with people who were in the loftiest political positions in the US. To quote the Washington Post from January 28, 1917, “No man in Europe commands a more sympathetic audience in America than Bryce.” What Toynbee did not share with his readers, even in his old age when he wrote Acquaintances, was that decades prior to World War One, Bryce had made a name for himself as a Liberal politician and an expert in foreign affairs thanks to raising the Armenian Question in 1876 as part of the larger Eastern Question raised by Gladstone and other anti-Muslim politicians, historians and journalists during the Bulgarian Agitation. It was imperialism, disguised as morality. Already in 1878, Bryce announced Turkey’s death, and presented the plan to cultivate “the growth of a native Christian race” – the Armenians – to the point of establishing “the nucleus of an independent state” – Armenia – whose territories would comprise of Ottoman land in the size of “about three hundred and fifty miles in length by two hundred and fifty in breadth.” Between then and World War One, Bryce engaged in many activities to organize the Armenians as a political entity within the Ottoman state that would replace the Ottoman sovereign. This was accompanied by the promotion of a conviction according to which the Turks as a race and as followers of Islam were inferior, uncivilized and an obstruction of progress. While giving the Romans Lecture in 1902 at Oxford, Bryce said that there are “cases in which the exclusion of the Backward race seems justified, in the interests of humanity at large,” and he invited his audience to “ Conceive what a difference it might make if Islam were within two centuries to disappear from the earth!” That’s a quote from 1902. Before World War One, before 9-11, before post-9/11ism supplanted postcolonialism. Before this idea of radical Islam became popularized. Bryce wanted Islam gone. It got in the way of his imperialist vision of the world.

If you were to study Bryce’s papers, you would find that all of the sources of falsehoods, cited by biased scholars or “credible independent experts,” whatever you want to call them, they are associated with Bryce, all of these sources are associated with Bryce. Go read his correspondence with the editors of the New York Times – see how much influence he had with them, with US government officials, with American church-organizers, with overseers of missionary activities in eastern Anatolia, with Armenian leaders in the US, Britain and eastern Anatolia. Go read his published articles in liberal periodicals, feel the hatred for the Turkish race and its Muslim religion, understand how the pretense of morality and values served an imperialist agenda, and become aware of the plotting that was going on. Then you will begin to wonder what facts are being denied here? How much is currently known on what led the British Liberals to promote Christian nationalism within the Ottoman Empire while they were in the opposition and Benjamin Disraeli was the premier? How does it relate to the rise of Darwinism at the time? How does it relate to anti-Semitism? How does it relate – on conceptual and interpersonal levels – to the rise of German anti-Semitism?

THE RISE OF RACISM, ISLAMOPHOBIA AND ANTI-SEMITISM IN BRITAIN

Bryce’s mentor in academia, the Oxford historian Edward A. Freeman was considered a spokesperson of sorts for Liberal Party ideology during Disraeli’s premiership, when the Liberal Party was in need of political pretext to win back the British public. He was described by historian Richard Shannon as “the natural leader of the Gladstonian historians.” Freeman wrote in 1877 that “the people of Aryan and Christian Europe” – the Christian minorities in the European territories of Ottoman Empire – were suffering from “ The union of the Jew and the Turk against the Christian.” To him, the Turk, much like the Jew, “did not belong to the Aryan branch of mankind” and did not belong in Europe. He elaborated on how the Jew and the Turk are the enemies of Europe. Upon visiting the US in the 1880s, in promotion of Anglo-Americanism, this was one of his impressions: “Very many approved when I suggested that the best remedy for whatever was amiss would be if every Irishman should kill a negro and be hanged for it.” Another observation: “The eternal laws of nature, the eternal distinction of colour, forbid the assimilation of the negroe.” And another one: “ The negro… is not a man and a brother in the same full sense in which every Western Aryan is a man and a brother. He cannot be assimilated; the laws of nature forbid it.” Or how about this: “…I must say that every nation has a right to get rid of strangers who prove a nuisance, whether they are Chinese in America, or Jews in Russia, Servia, Hungary, and Roumania.” This man was a racist, and he coached Bryce to develop the political potential of the Armenian people in Ottoman land, by highlighting their supposed superior race and religion. I am not bringing forth these quotes to judge a man according to our postmodern-postcolonialist standards. I am bringing these quotes before you to show that this is the frame of mind that propelled the British imperialist idea to pin the Armenian people against the Turks. There was a racial intensity that had proven effective then, and has been overlooked in academia to this day.

The anti-Semitism shown against Disraeli, by these same people, was a new Darwinian-inspired anti-Semitism. It was a blood based, race based, anti-Semitism. It did not aim against Disraeli for being a practicing Jew, for “killing Jesus,” for working on Sundays, for not believing, because Disraeli was Anglican, he was baptized as a boy. This was not the anti-Semitism of the Middle-Ages, but the anti-Semitism that was later promoted in Germany by the likes of Houston Stewart Chamberlain, a Briton in Germany, who grew up supporting Gladstone against Disraeli. The spiritual leader of Nazi racism was influenced by the anti-Semitism that developed in Britain during the time of the Bulgarian Agitation and the raising of the Armenian question. In the Holocaust, Jews were persecuted by the Nazis systematically, not because of religious differences but because of racial beliefs; certainly not because of a rebellion. The Jews were loyal Germans who participated in German culture and were proud of their German national home. The argument that feeds on comparisons between the Holocaust and a tragedy that followed Armenian, British sponsored, rebellion, is unacceptable. To suggest that Hitler was right when he equated – if he did – the Jews or the Poles to the rebellious, British-sponsored, Armenians, is unacceptable. It is important to internalize that the same people in Britain who wanted an Armenian independent state on Ottoman land were the ones who claimed that the Jews were never to be accepted in their European national homes. They were the racists who invented modern racism. Bryce wrote about Disraeli that he was not an Englishman. Disraeli was his prime-minister, English born and Anglican, and yet Bryce wrote about him that he was not really an Englishman. Why? Because Disraeli had Jewish blood.

THE HISTORIOGRAPHICAL PROBLEM

This is a big problem to this day – can the Jews be considered Englishmen or Englishwomen in Britain? Can the Muslims? Can the Turks? And how about in Australia? Are the Turks here Australians? We might receive an illuminating understanding of it if we were to address British historiography on the Armenian issue, on anti-Turkish, anti-Muslim, anti-Ottoman, anti-Semitic aspects of it, openly and sincerely. Instead of letting part-time scholars keep this fascinating and important period of history as part of a political game, let’s open up the books. Let’s read what was said at that time in Britain, and try to understand how this might be connected to the current national identity crisis in Britain and in Western states. How is an African Muslim to become aligned with British national identity? This is the basic problem. More basic than the tension due to the fighting of Western militaries in Muslim countries. The basic problem is that British historiography has not owned up to its hateful prejudice. Statements such as that made by William Gladstone, the much revered four-time prime-minister of Britain – elected more times than anybody in British history to be the premier – who ran policies against Muslims in Turkey and Egypt. He said: “It is not a question of Mahometanism simply, but of Mahometanism compounded with the peculiar character of a race… They [the Turks] were, upon the whole, from the black day when they first entered Europe, the one great anti-human specimen of humanity.” How can one expect Muslims to feel like they are a part of national identity, when such words are unaccounted for, and the man who said them is enshrined, literally, a figure that is a source of pride in Britain’s modern history? How has this tension between British pride in its anti-Muslim history and the pretense of bogus morality for imperialist gains been reconciled with its current social makeup?

We can ask even further, what about British history of slave ownership? Has that been addressed? How many of you know that William Gladstone’s father, John, was one of the wealthiest slave owners in Liverpool? How many of you know that in his plantations Africans were hanged or shot down when they wanted to set themselves free? How many of you know that he was one of the most passionate voices in Britain against abolition, and that he called William Wilberforce – who was the leader of the anti-slavery campaign – he called him a “mistaken man,” and that he only gave up the fight once the government paid him a huge sum of money as compensation? How many of you knew that? There is no attempt of owning up to this history, of addressing the fact that William Gladstone was not so moral or that his father was not a philanthropist (a philanthropist they still call him!); there is no attempt to recognize that the anti-Turkish use of Armenians as colonialist pawns against the so-called “antihuman” Turks, is mentally related to the use of African slaves, just as the Gladstones – father and son – are related. There are churches in the Liverpool area that were built with slave money, and yet the name Liverpool does not make the common person think first of slavery; instead, people think of the Beatles and Ian Rush.

IS AUSTRALIA A FAIR PLACE FOR ALL ITS CITIZENS?

David Cameron, in his first speech as Britain’s prime-minister blamed state multiculturalism for the national identity crisis of Muslims in Britain. They have been allowed to live their separate lives for too long, he said. Why wouldn’t he say that? It is politically popular to take action against Muslims in Western societies in our post-9/11 world, and it means that Britain does not have to change its national identity, that it does not have to recognize a deep disrespect to the formerly colonized people who are now among its citizens. And here in Australia, a relatively new settler state, has it not been shown that when there isn’t a historiography that is filled with anti-Muslim moments, multiculturalism actually works? So what if Muslims or Turks prefer to maintain their traditional customs and live in their own neighborhoods? They still might watch Neighbours and Home and Away, if they are comfortable. If their historical background is truly respected by Australia, they will be proud Australians. It is not advisable to create a national identity crisis for Turks or Muslims in Australia by following a political ordinance from the US or the UK to twist history. Historiographical cleanliness is crucial for keeping national identity intact. How would Muslims or Turks feel about having to send their children to Australian schools if lies are taught about their people’s heritage?

This is my message to you. Historiographical cleanliness goes a long way. The study of historical facts must be on full display. The approach taken by you on the characterization of the events in 1915-16 defines your national identity. Is Australia a fair place for all its citizens? May all of Australia’s citizens be proud of their government’s fairness in choosing historical study over prejudice, or is Australia a country that receives political dictations on history?

Thank you!

24. November 2014

NEW SOUTH WALES PARLIAMENT

AUSTRALIA