Turkey and the Caucasus

Waiting and watching

Aug 21st 2008 | ANKARA AND YEREVAN

From The Economist print edition

A large NATO country ponders a bigger role in the Caucasus

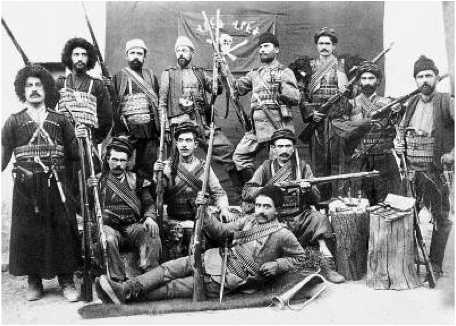

APErdogan plays the Georgian flag

AT THE Hrazdan stadium in Yerevan, workers are furiously preparing for a special visitor: Turkey’s president, Abdullah Gul. Armenia’s president, Serzh Sarkisian, has invited Mr Gul to a football World Cup qualifier between Turkey and its traditional foe, Armenia, on September 6th.

If he comes, Mr Gul may pave the way for a new era in the Caucasus. Turkey is the only NATO member in the area, and after the war in Georgia it would like a bigger role. It is the main outlet for westbound Azeri oil and gas and it controls the Bosporus and Dardanelles, through which Russia and other Black Sea countries ship most of their trade. And it has vocal if small minorities from all over the region, including Abkhaz and Ossetians.

Turkey’s prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has just been to Moscow and Tbilisi to promote a ‘Caucasus Stability and Co-operation Platform’, a scheme that calls for new methods of crisis management and conflict resolution. The Russians and Georgians made a show of embracing the idea, as have Armenia and Azerbaijan, but few believe that it will go anywhere. That is chiefly because Turkey does not have formal ties with Armenia. In 1993 Turkey sealed its border (though not its air links) with its tiny neighbour after Armenia occupied a chunk of Azerbaijan in a war over Nagorno-Karabakh. But the war in Georgia raises new questions over the wisdom of maintaining a frozen border.

Landlocked and poor, Armenia looks highly vulnerable. Most of its fuel and much of its grain comes through Georgia’s Black Sea ports, which have been paralysed by the war. Russia blew up a key rail bridge this week, wrecking Georgia’s main rail network that also runs to Armenia and Azerbaijan. This disrupted Azerbaijan’s oil exports, already hit by an explosion earlier this month in the Turkish part of the pipeline from Baku to Ceyhan, in Turkey.

‘All of this should point in one direction,’ says a Western diplomat in Yerevan: ‘peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan.’ Reconciliation with Armenia would give Azerbaijan an alternative export route for its oil and Armenia the promise of a new lifeline via Turkey. Some Armenians gloat that Russia’s invasion of Georgia kyboshes the chances of Azerbaijan ever retaking Nagorno-Karabakh by force, though others say the two cases are quite different. Russia is not contiguous with Nagorno-Karabakh, nor does it have ‘peacekeepers’ or nationals there.

Even before the Georgian war, Turkey seemed to understand that isolating Armenia is not making it give up the parts of Azerbaijan that it occupies outside Nagorno-Karabakh. But talking to it might. Indeed, that is what Turkish and Armenian diplomats have secretly done for some months, until news of the talks leaked (probably from an angry Azerbaijan).

Turkey’s ethnic and religious ties with its Azeri cousins have long weighed heavily in its Caucasus policy. But there is a new worry that a resolution calling the mass slaughter of Armenians by the Ottoman Turks in the 1915 genocide may be passed by America’s Congress after this November’s American elections. This would wreck Turkey’s relations with the United States. If Turkey and Armenia could only become friendlier beforehand, the resolution might then be struck down for good.

In exchange for better relations, Turkey wants Armenia to stop backing a campaign by its diaspora for genocide recognition and allow a commission of historians to establish ‘the truth’. Mr Sarkisian has hinted that he is open to this idea, triggering howls of treason from the opposition. The biggest obstacle remains Azerbaijan and its allies in the Turkish army. Mr Erdogan was expected to try to square Azerbaijan’s president, Ilham Aliev, in a visit to Baku this week. Should he fail, Mr Gul may not attend the football match—and a chance for reconciliation may be lost.