|

|

|

Maxime Gauin

JTW Columnist

|

This column is a reaction to one of Mustafa Akyol’s in Hürriyet Daily News, published on April 25, 2012.

There is absolutely nothing personal, or even ideological, in this response; I want only to respond to these precise points, as a historian working on the Armenian question.

Mr. Akyol alleges that “the nationalist Young Turk government decided to expel almost all Armenians to Syria” and that “The ‘Turkism’ of the Young Turks, Kaplan reminded, yearned for not a plural nation of many faiths and ethnicities, but an exclusive ‘Turkish homeland.’”

The Ottoman census counted around 1,300,000 Ottoman Armenians on the eve of 1914. This census undercounts both Muslims and non-Muslims, for technical reasons (a lack of material and human power to count everybody, especially in eastern Anatolia and Arab lands). The most serious estimations count around 1,700,000-1,750,000 Armenians.[1]

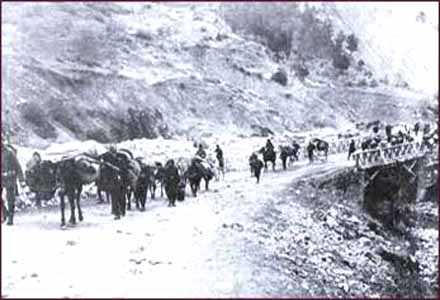

There is no definitive study on the number of relocated Armenians. The Ottoman sources indicate that 438,758 Armenians were relocated until the beginning of 1916 to Arab provinces, including 382,148 who arrived at their destination and 56,612 who perished.[2]Certainly, more perished due to illness or being attacked by Arab tribes, especially during the year 1916; others had been killed in inter-communal clashes in Van, Urfa, and some other cities. There are also reasons to believe that the account of relocated Armenians is not comprehensive.[3]

Now, let’s look at the Armenian sources. In 1918, Boghos Nubar, co-president of the Armenian delegation in the Paris peace conference, estimated the total to be 600 or 700,000.[4] In addition, the Russian army relocated about 300,000 Armenians (half whom perished, surely not because of any “ethnic cleansing” design)[5], and some others were relocated from one Anatolian town to another.

As a result, to pretend that “the nationalist Young Turk government decided to expel almost all Armenians to Syria” is at least questionable and an overly simple assertion.

Most of the Armenians of Ystanbul (160,000), Yzmir (13,000), Edirne (33,650), Kastamonu (13,700), Kütahya (several thousand), Antalya (at least 500), Mara? (6 or 7,000), and Aleppo (22,000)were not relocated during WWI, and neither were thousands of Armenians who were Catholics, Protestants, artisans or parents of soldiers.[6] They were not because they did not represent a threat to the Ottoman State’s security.

Indeed, it should be noted that there was no “Turkism” in the main reasons for the relocation. If the CUP “yearned for not a plural nation of many faiths and ethnicities, but an exclusive ‘Turkish homeland,’” why did this party accept Christians, Jews and non-Turkish Muslims, not only as members, but also for high positions, like mayors, deputies and ministers?

The presence of Jews, including Emmanuel Carasso, a leader of the Young Turks, provoked anti-Semitic reactions against the CUP from various factions. The Young Turks supported the election of its sympathizer Bedros Kapamaciyan as mayor of Van in 1909. Kapamaciyan was assassinated by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation in December 1912.[7]The CUP promoted Gabriel Noradunkian to minister of commerce in 1908, despite him havingmade his career as a top-rank civil servant under Abdülhamid. Noradunkian served as minister of foreign affairs in the anti-CUP government of 1912-1913. Regardless, the CUP, coming back to power in January 1913, proposed several times, in vain, that Noradunkian remain in his position.[8] From January 1913 to November 1914, the minister of PTT, Oskan Mardikian (member of the CUP), was Armenian, and the minister of public works, SülaymanBustani, was a Christian Arab. Both resigned because they supported the neutrality of the Ottoman Empire; the majority of the CUP leaders considered maintaining the neutrality to beimpossible.

In summer 1914, the CUP proposed in vain that Boghos Nubar become the Ottoman minister of foreign affairs. The Armenian insurrections (see below) did not provoke an absolute and general distrust of Armenians by the CUP leaders. Indeed, Berç Keresteciyan, deputy director general of the Ottoman Bank, was promoted to director general during WWI. Keresteciyan supported the Kemalist movement during the Turkish war of independence, and was a deputy of Afyon from 1935 to 1946.

It should also be noted that even Enver Pasha was a staunch supporter of the full integration of non-Muslims in the Ottoman army, at least until 1914.[9]

Mr. Akyol rightfully praised the book of Guenter Lewy on the Armenian question. This book contains a devastating analysis of the allegations against Ziya Gökalp, an intellectual and member of the CUP central committee, wrongly presented as a chauvinist and anti-Christian.[10]

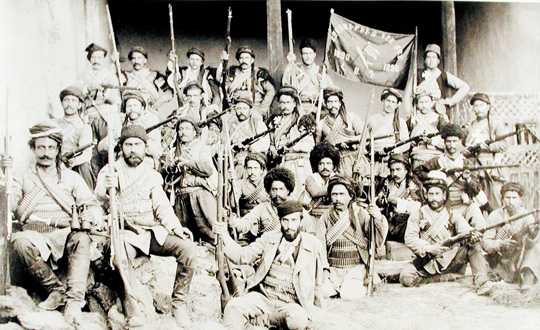

What motivated the Ottoman government in 1915 to relocate a portion of the Armenian community? Chiefly, military and security reasons. In addition to the well-known insurrection in Van (April 1915), other important revolts took place in Zeytun (August 1914, February 1915) and Bitlis. Insurrectional activities were organized in Cilicia as well, with the Armenian committees hoping for and repeatedly making claims of an Anglo-French landing. Even in the Bursa region, there were Armenian gangs attacking the Ottoman army and Muslim civilians. Considering the atmosphere of panic in spring 1915 and the limited number of roads in the Ottoman Empire, the decision is easy to understand.[11] The gradual reaction of the Istanbul authorities is another argument against the “ethnic cleansing” allegation: The insurrectional movement in Zeytun was crushed in the relocating of the Armenians of this city to Konya, instead of Arab lands; and as late as May 2, 1915, Enver suggested relocating only the Armenians living in the vicinity of Lake Van.[12]

“Ethnic cleansing” was so far from the Ottoman government’s mind that, as early as 1916-1917, several thousand Anatolian Armenians were allowed to goback to Urfa.[13]

It is perfectly true, however, that the Armenian committees, assisted by the Greek government, prevented the coexistence of communities in Cilicia through intense and misleading propaganda.[14] Similarly, the Greek army practiced a scorched earth policy during its retreat of 1922, which not only included a general burning of all villages and cities, as well as numerous massacres, but also the forced exile of Christians, to undermine the recovery of the Turkish economy after the peace treaty.[15] This was a kind of “ethnic cleansing.”

If the descendants of Christian Anatolians want to present grievances, if Turks want to show a “common pain,” they should logically begin presenting their critiques to Athens and to the headquarters of the three old Armenian nationalist parties, namely the ARF, Hunchak and Ramkavar.

[1] Guenter Lewy, The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005, p. 235; Justin McCarthy, “The Population of the Ottoman Armenians,” in TürkkayaAtaöv (ed.), The Armenians in the Late Ottoman Period, Ankara: TTK/TBMM, 2001, p. 70, https://web.itu.edu.tr/~altilar/tobi/e-library/TheArmenians/thearmenians_table2page70.gif

[2] Yusuf Halaço?lu, “Realities Behind the Relocation,” in TükkayaAtaöv (ed.), The Armenians in the Late…, pp. 130-133, https://web.itu.edu.tr/~altilar/tobi/e-library/TheArmenians/Relocation.pdf

[3] GuenterLewy, The Armenian Massacres…, pp. 198-203, 209-220 and 236.

[4]

[5] Richard G. Hovannisian, Armenia on the Road to Independence. 1918, Berkeley-Los Angeles-London: University of California Press, 1967, p. 67.

[6]Kemal Çiçek, “Relocation of the Ottoman Armenians in 1915: A Reassessment,” Review of Armenian Studies, n° 22, 2010, pp. 120-121; Yusuf Halaço?lu, The Story of 1915. What Happened to the Ottoman Armenians?, Ankara: TTK, 2008, pp. 52 and 91; GuenterLewy,The Armenian Massacres…, pp. 158, 165, 180, 186-187, 191, 203-205; HikmetÖzdemir and Yusuf Sarynay, Turkish-Armenian Conflict Documents, Ankara: TTK/TBMM, 2007, pp. 119, 127, 175, 201, 203, 207, 213- 221, 237, 265, 283, 321, 339, 341.

[7]HasanOktay, “On the Assassination of Van Mayor Kapamacyyan by the Tashnak Committee,” Review of Armenian Studies, I-1, 2002, pp. 79-89, http://www.eraren.org/index.php?Lisan=en&Page=DergiIcerik&IcerikNo=94; KaprielSeropePapazian, Patriotism Perverted, Boston: Baikar Press, 1934, p. 69.

[8]YücelGüçlü, The Holocaust and the Armenian Case in Comparative Perspective, Lanham-Boulder-New York-Plymouth: University Press of America, 2012, pp. 85-86.

[9]Odile Moreau, L’Empire ottoman à l’âge des réformes. Les hommes et les idées du « Nouvel Ordre » militaire (1826-1914), Paris : Maisonneuve et Larose, 2007, pp. 49-50 and 70-71,

[10] Guenter Lewy,The Armenian Massacres…,pp. 43-47.

[11]Numerous references in MaximeGauin, “The Convergent Analysis of Russian, British, French and American Officials Regarding the Armenian Volunteers (1914-1922),” International Review of Turkish Studies, I-4, Winter 2011-2012, pp. 13-16,

[12]Yusuf Halaço?lu, “Realities Behind the Relocations…”, pp. 109-110; Facts on the Relocation of Armenians. 1914-1918, Ankara: TTK, 2002, pp. 58-60 and 67-68; GuenterLewy, The Armenian Massacres…, p. 307, n. 4.

[13]GuenterLewy, The Armenian Massacres…, pp. 203 and 215.

[14] Background and references in MaximeGauin, “The Convergent Analysis…”, pp. 34-41.

[15] See, for instance,MevlütÇelebi (ed.),Greek Massacres in Anatolia on Italian Archive Documents, Ankara: AAM, 2010, pp. 102-110; Rapport d’ElzéarGuiffray, administrateur délégué de la Société des quais de Smyrne, 27 juillet 1922 ; Raymond Poincaré au colonel Mougin, 7 septembre 1922 ; Colonel Mougin au général Pellé, 8 septembre 1922 ;Ministère des Affaires étrangères au représentant français à Athènes, 8 septembre 1922 ; ministère aux ambassadeurs à Londres, Rome et Washington, 8 et 9 septembre 1922 ; Général Pellé au ministère des Affaires étrangères, 12 septembre 1922 ; ministère au chargé d’affaires à Washington, 26 septembre 1922, Archives du ministère des Affaires étrangères, P 1380 (the microfilm P 1380 is full of French documents regarding the Greek scorched earth policy). |