Category: Serap Korkmaz Erdoğdu

Turkish Traditions

-

Turkish Kilim Symbols

Most Turkish kilim designs have their roots in the conservative, indigenous, pre-Christian and pre-Islamic backgrounds of the rural population and are related to the basic themes of life: birth, marriage, fertility; spiritual life and happiness; love and unison; and death. They reflect the ancient cults and practices of their ancestors around these events. There are many symbols in the vocabulary of the weaver and many stylizations of each symbol. Unlocking the keys to these symbols reveals a deeper insight into the values, dreams and culture of the Anatolian people and expresses layer upon layer of history and influence in the region.

-

Story Behind the Turkish Idiom “Pabucu Dama Atılmak”

Pabucu Dama Atılmak – Shoe to be thrown to the roof ” to lose favor; to fall from popular esteem; to seem less appealing; to look pale by comparison”…..

The story behind the idiom “Pabucu Dama Atilmak” – to throw someones shoe on the roof is…

At the time of the Ottoman, the organisation the artisans and craftsmen belonged to would regulate trade along with social life. They had come up with an interesting method to try to prevent defective goods, cheap production (with intention of less material, more profit), and bad quality work.

Let’s say you bought a shoe and had it fixed, but it was flawed. The committee would listen to both sides of the story- the plaintiff (customer) and the craftsman. If the plaintiff’s complaint was found to be legitimate, the cost of the shoe would be paid back to him and the shoe itself would be thrown on the roof of the shoemaker as a warning or deterrent to others.

This way, passer-by’s and future customers would know who is a good shoemaker and who isn’t just by looking at their rooftops.

The shoemakers whose shoes are thrown to the roof would thereby lose out on financial earnings, and lose potential customers thus it would be as if HIS “shoe was thrown on the roof”.

The shoemakers whose shoes are thrown to the roof would thereby lose out on financial earnings, and lose potential customers thus it would be as if HIS “shoe was thrown on the roof”. -

Decorating Pine Tree was a Turkish Ritual

Famous all around world Sumerian specialist Dr. Muazzez İlmiye Çığ said pine tree which used Christmas tree was a Turkish ritual. Pine tree which used Christmas tree spreads to Christian world at century 16. And Turks had been celebrated new year at 22 December when the longest night of year. They had been celebrated new year while decorate pine tree.

Sumerian specialist Dr. Muazzez İlmiye Çığ talk about a tree which named “Akçam’. It is a kind of pine tree. Akçam just used to grew at Turkistan. Turks used to bring Akçam to homes and they used to put some gifts for God under that tree. They used to bind some doeks to boughs. They used to give thanks to God because of God had been given them a good life at pass year. Families used to wear good clothes and visit each one of them and elders. “This ritual reached to Europe. Pine tree isn’t about Noel. Christians accepted as Jesus birth the pine tree at İznik Concile. But Christians didn’t decorate pine tree. This ritual has begun in Germany century 16. It reached to France and spread all around world” said Dr. Çığ.Turks still have been featured to tree. They decorate with some doeks not only pine but some others trees too. They make some vows. Some Turks perceives the making vow means paganism. This tradition attends with local people. More High-educated, high-income and city people see this tradition at some movies, stories or ads. Some of city people buy noel tree and decorate them at Turkey. All these appear that Dr. Çığ’s claims may be right. Turks left all Shamanist totems after adopt Islam. I think decorating pine tree and putting some gift under that were perceived against Islam. And they began to celebrating the New Year according to Islam. They left celebrating December 22. And noel tree turned back Turkish high-level people as Europe and American ritual after centuries.

-

Safranbolu & Traditional Turkish Houses

The known history of Safranbolu, located near the north western Black Sea coast of Anatolia, in Karabük nearby Zonguldak, dates back as far as 3000 BC. Once a city of Roman Province of “Paphlagonia”, Safranbolu has hosted many civilizations including the Roman, Byzantine, Seljuk and Ottoman Empires throughout its history. During the Ottoman era the town served as an important junction on the Kastamonu – Gerede (Bolu)- Istanbul route of the famous silk road. Safranbolu was at the same time a popular residence for Ottoman Royalty close to the Sultan and Grand Viziers. The city received its name from the saffron which is native in Safranbolu. The powder obtained from its flower is a very strong dye. Used in very small quantities, saffron adds a delicate flavor, distinct aroma and a very unique color to deserts and other food in the Turkish Cuisine. It is also used for some Turkish carpets as a unique dye. Also unique in Safranbolu is the famous Çavus grapes with its extremely thin skin and sweet flavor. Safranbolu displays its extremely rich historical and cultural heritage through 1008 architectural structures displaying a good example of Turkish architecture, all preserved in their original environment. These structures include the public buildings such as Cinci Hodja Kervansaray and Cinci Hodja Hamam, Mosques of Koprulu Mehmet and Izzet Mehmet Pashas, The Tennaries Clock tower, Old hospital premises, The guild of shoe makers, The Incekaya aqueduct, The old city hall and fountains as well as hundreds of private residences. Rock tombs and tumulus just outside the city are also of interest. Safranbolu was placed in the world Cultural Heritage list by UNESCO in appreciation of the successful efforts in the preservation of its heritage as a whole. Safranbolu has deserved its real name for its houses. These houses are perfect examples of old civilian architecture, reflecting the Turkish social life of the 18th and 19th centuries. The size and the planning of the houses are deeply affected by the large size of the families, in other words a total members of a big family living together in one house. The impressive architecture of their roofs have led them to be called as “Houses with five façades”. The houses are two or three storied consisting of 6 to 9 rooms, each room is entirely detailed and have ample window space allowing plenty of light. The delicate woodwork and carved wall and ceiling decorations, the banisters indoor knobs etc. all come together to form an unmatched harmony of architectural aesthetics and Turkish art.

Being strong and durable, functional, economical and aesthetic are the basic characteristics of the traditional Turkish house. The houses are built along the roads and on the edges of the squares in an order which reflects a strong respect for the neighbors. In most cases, the houses on both sides of the roads, which follow the configurations of the land, are separated with high walls and have overhanging sections on these walls, reaching towards the street. Entrance to the house is generally through an inner door which opens onto the garden. When household chores permitted, the lady of the house, whose privacy is ensured with the high walls, would go upstairs and look around and chat with neighbors from the overhanging windows of the hall which face either the street or the garden. The large windows of the upper floors protected with bars or grills allowed this outlet. Inside, the rooms were placed around a common space called sofa (hall), either on one or two sides or all around it. Sofas were in a sense interior court yards. It is an area which provides work space during the daily life as well as facilitating circulation among the rooms. They are opened to the outside sometimes completely on one side and sometimes on both sides. The rooms were arranged to meet all the needs of their occupants. There, one could sit and rest, sleep, eat, worship, work and even take a bath. The recessed cupboards, open shelves, storage cupboards and places for washing lining the walls functioned as built in furniture. The divans placed in front of the windows were both seats and beds and left centers of the rooms free. The main living area of the house was the upper floor while the ground floor was allocated to service spaces.The materials used in the houses varied according to the regions and climatic conditions. Wood and stone were used in the Black Sea Region, while it was stone and wood according to the locale in the West and the South and combinations of mud brick and wood in the Center and the Eastern parts of the country.

-

Village institutes’ (Köy enstitüleri)

In the 40s, Turkiye experimented with elevating the education level in the countryside. `Village institutes’ (Köy enstitüleri) were founded according to the ideas of philosopher-educator John Dewey, who had visited Turkey in 1924. In his opinion classical education had to be combined with practical abilities and had to be applied to local needs. However, it was the central government which regulated this by law. Mid September lessons started for the pupils of the village institutes. They took theoretical and practical lessons which were supposed to be useful for daily life in the village. There was also resistance against this secular and mixed education. It was feared that it would educate ‘the communists of tomorrow’. In 1953 the village institutes were closed.

In the 40s, Turkiye experimented with elevating the education level in the countryside. `Village institutes’ (Köy enstitüleri) were founded according to the ideas of philosopher-educator John Dewey, who had visited Turkey in 1924. In his opinion classical education had to be combined with practical abilities and had to be applied to local needs. However, it was the central government which regulated this by law. Mid September lessons started for the pupils of the village institutes. They took theoretical and practical lessons which were supposed to be useful for daily life in the village. There was also resistance against this secular and mixed education. It was feared that it would educate ‘the communists of tomorrow’. In 1953 the village institutes were closed. -

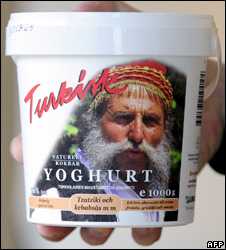

Yoğurt “Yogurt”

The word is derived from Turkish yoğurt, and is related to yoğurmak ‘to knead’ and yoğun “dense” or “thick”.

There is evidence of precultured milk products being produced as food for at least 4,500 years. The earliest yoghurts were probably spontaneously fermented by wild bacteria.The oldest writings mentioning yogurt are attributed to Pliny the Elder, who remarked that certain nomadic tribes knew how “to thicken the milk into a substance with an agreeable acidity”. The use of yoghurt by medieval Turks is recorded in the books Diwan Lughat al-Turk by Mahmud Kashgari and Kutadgu Bilig by Yusuf Has Hajib written in the 11th century. Both texts mention the word “yoghurt” in different sections and describe its use by nomadic Turks.

There is evidence of precultured milk products being produced as food for at least 4,500 years. The earliest yoghurts were probably spontaneously fermented by wild bacteria.The oldest writings mentioning yogurt are attributed to Pliny the Elder, who remarked that certain nomadic tribes knew how “to thicken the milk into a substance with an agreeable acidity”. The use of yoghurt by medieval Turks is recorded in the books Diwan Lughat al-Turk by Mahmud Kashgari and Kutadgu Bilig by Yusuf Has Hajib written in the 11th century. Both texts mention the word “yoghurt” in different sections and describe its use by nomadic Turks.