The big question in Turkey at the moment is whether Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan will run for president in August.

There is every indication he will. At a meeting of the Justice and Development Party’s (AK Party) Central Decision and Administration Board (MKYK), it was decided to maintain the party’s rule that a deputy should serve for a maximum of three terms, which rules out the prime minister’s leadership after the 2015 elections. Unless Erdoğan intends to twiddle his thumbs, which is unlikely, his only option is take over from President Abdullah Gül. Provided he is elected.

At the beginning of April, Prime Minister Erdoğan indicated that the new president would not just be a protocol president but would exercise the executive powers provided to him by the Constitution. As he put it, he would be “a sweating, running, ordering president.” Article 104 of the Constitution entitles the president to preside over the Council of Ministers or to call the Council of Ministers to meet under his chairmanship, and it is undoubtedly this provision that Erdoğan intends to use since the failure of the constitutional commission to transform the presidency into an executive one.

President Gül has ruled out a Putin-Medvedev switch, and it is believed a deputy prime minister will function as caretaker until Gül can stand for Parliament in the 2015 elections and himself become prime minister. One of the Turkish president’s duties is to defend the Constitution and, if necessary, either to return laws to the Turkish Parliament to be reconsidered or refer them to the Constitutional Court for annulment, either in part or in whole.

This is undoubtedly why Gül has chosen to soft-pedal his presidency and sign the controversial Internet, Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK) and National Intelligence Organization (MİT) laws, so as not to ruffle the feathers of his prospective supporters in the AK Party. Despite international protests, in January without demur President Gül signed a bill criminalizing emergency medical care and penalizing doctors with imprisonment for up to three years and fines of nearly $1 million.

A total of 255 protesters are now being tried for participating in the Gezi Park demonstrations last May and June, some of whom took refuge in the Dolmabahçe mosque to escape police tear gas. Two doctors who rendered emergency aid to the victims are also being charged for “praising a criminal, insulting religious values and damaging a mosque.” As they explained, if they hadn’t helped, many people would have died or lost limbs.

Constitutional Court

Therefore, it must have been embarrassing for Prime Minister Erdoğan and President Gül together with other members of the AK Party government to be lectured by the president of the Constitutional Court, Haşim Kılıç, on rule of law in his speech to celebrate the 52nd anniversary of the founding of the court.

Defining the role of the judiciary as “the conscience of the state,” Kılıç rejected the use of the judiciary as logistical support for political ideas and ideologies and for revenge against adversaries. Furthermore, he called for documentation and evidence of Erdogan’s claim of a “parallel state” and a “gang” inside the judiciary and accused the government of “corruption of conscience.”

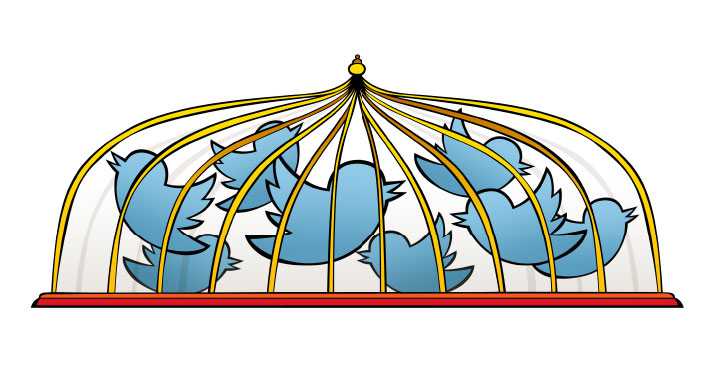

Kılıç likewise dismissed the claim that the Constitutional Court (in its partial annulment of the HSYK law and lifting of the Twitter ban) had acted for political purposes and against the interests of the nation as “shallow.”

In a clear reference to the AK Party government’s attempts to limit or even ban the use of information technology, the chief judge quoted Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev’s remark that in the age of globalization, one cannot issue visas to antennas.

It is the duty of Turkey’s president to appoint members of the Constitutional Court, and if Erdoğan accedes to the presidency, what will happen is a foregone conclusion, as only 10 months remain of Haşim Kılıç’s term of office. Regulatory boards and other institutions have already been stacked with AK Party appointees, and now 110 AK Party-affiliated judges with no previous experience have been appointed to high criminal courts.

Corruption

After an unruly debate in Parliament, an AK Party-dominated commission has been established to investigate charges of corruption against four ex-ministers, which will undoubtedly lead to their acquittal. In the meantime, a newly appointed İstanbul public prosecutor has dismissed charges concerning illegal construction permits against 60 suspects, including the son of the former environment and urban planning minister and a construction tycoon.

At the recent Financial Times Turkey Summit 2014 in İstanbul, Finance Minister Mehmet Şimşek defended the AK Party government’s purge of several thousand police officers, hundreds of public prosecutors and judges as well as senior functionaries as “extraordinary measures” to deal with what the prime minister has called “a judicial coup.” However, he assured participants that the government’s source of inspiration was still the EU in terms of cementing the rule of law and advancing towards a better democracy. “This is our fundamental point of reference.”

This is at odds with the contention of Prime Minister Erdoğan’s economic adviser, Yiğit Bulut, who said that “we no longer need Europe and its material and moral affiliates which may become a burden on us.” Bulut is believed to have convinced Erdoğan to delay raising interest rates to defend the lira, and last summer he claimed that dark forces were plotting to kill the prime minister with telekinesis.

The EU’s enlargement commissioner, Stefan Füle, has admitted that events in the last few months have cast doubt on Turkey’s commitment to European values and standards. Germany’s president, Joachim Gauck, has openly declared that “the current developments in Turkey horrify me,” and Jean-Claude Juncker, who is running for president of the European Commission, has called for an “enlargement pause.”

Şimşek has admitted that Turkey is corrupt, although he said there has been progress in the last decade. But at a meeting of the World Forum on Governance in Prague, President of the Italian Senate and former anti-Mafia prosecutor Pietro Grasso remarked that the way to get rid of corruption cannot be to get rid of those who fight against corruption.

Ali Yurttagül, who for more than 25 years was adviser to the Greens in the European Parliament, also believes that Turkey is not producing laws compatible with EU norms anymore and is suspending the rule of law.

Nevertheless, Turkey’s EU Affairs Ministry has after a meeting of the Reform Monitoring Group (comprising Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu and the newly appointed ministers for EU affairs, the interior and justice) put out a statement, declaring, “It is not understandable for some EU member states and EU officials to make statements […] about the democratization package, basic rights and freedoms, including the freedoms of expression, the press and the freedom to organize, which are improving every day with the [government’s] reforms.”

Parallel universe

The AK Party government has defended itself against serious charges of corruption with a counterclaim that the graft probe that went public on Dec. 17 was an attempted coup instigated by a “parallel state” controlled by a cleric, Fethullah Gülen, who lives in Pennsylvania. One could also argue that the same government is living in a parallel universe controlled by the dyad of Davutoğlu and Erdoğan.

Foreign Minister Davutoğlu, both as Prime Minister Erdoğan’s chief foreign policy adviser and later as foreign minister, has clearly inspired Erdoğan with his grandiose vision of Turkey’s role in the world. Davutoğlu has formulated a policy of “strategic depth” based on engagement with countries with which Turkey shares a common past and geography, and envisages Turkey not only as the epicenter of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Caucasus but also as the center of Eurasia.

This policy, dubbed neo-Ottomanism, also envisages Turkey playing an important role in setting the parameters of a new world order (“nizam-i âlem”) under Islam. Last year, in an address to the party faithful in Bursa, Professor Davutoğlu dismissed the last century as a parenthesis and stated that Turkey would once again unite Sarajevo with Damascus and Benghazi with Erzurum and Batumi.

This theme was echoed in a speech given by Prime Minister Erdoğan’s present chief adviser, Ibrahim Kalın, at the İstanbul Forum in October 2012, where he spoke of a new geopolitical framework and Turkey’s pivotal role. Moreover, the traditional foreign policy goal of advancing a state’s national interests would be replaced by “a value-based and principled” foreign policy.

The same obsession with a renaissance of Turkey’s Ottoman past is reflected in Erdoğan’s rhetoric. At the AK Party’s congress in September 2012 the prime minister declared that the government was following the path of Ottoman Sultans Mehmet II and Selim I, and it is no coincidence that the new bridge over the Bosporus has been named after Selim I, who was responsible for the expansion of the Ottoman empire.

After the AK Party’s victory in the 2011 elections, Erdoğan declared: “Today Sarajevo won as much as İstanbul, Beirut won as much as İzmir, Damascus won as much as Ankara, Ramallah, the West Bank, Jerusalem and Gaza won as much as Diyarbakır. Today the Middle East, the Caucasus, the Balkans and Europe won as much as Turkey.”

Likewise, after his return from a trip to North Africa last June, Erdoğan sent greetings to İstanbul’s brother cities Sarajevo, Baku, Beirut, Skopje, Damascus, Gaza, Mecca and Medina, but there was no mention of Europe.

Primarily because of the Turkish government’s attempt to enforce regime change in Syria, Turkey’s foreign policy in the Middle East has been a disaster. Two years ago Davutoğlu proclaimed in Parliament: “A new Middle East is about to be born. We will be the owner, pioneer and servant of this new Middle East.”

Now Syria is ravaged by civil war, more than 9 million Syrians have left their homes, including over 2 million who have fled to neighboring countries Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. Rather than exercising a strong, moderating influence, Turkey has become a party to the conflict, acting as a hub for support not only for the Free Syrian Army (FSA), but also al-Qaeda-affiliated groups.

Consequently, President Gül has suggested that Turkey needs to recalibrate its foreign and security policies, taking into account the new realities that stem from the power vacuum in Syria. These include the declaration of three autonomous Kurdish administrations in northern Syria, which has now been put forward as a demand by Turkish Kurds for the predominantly Kurdish Southeast.

Ozymandias

Against this backdrop, a speech made by Foreign Minister Davutoğlu in Konya last month seems misplaced. According to the minister, the AK Party was not just a political party movement but a great historical movement that could not be stopped until doomsday. This is the same minister who in a brief on Turkish foreign policy two years ago stated, “… We formulate our policies through a solid and rational judgment of the long-term historical trends and an understanding of where we are situated in the greater trajectory of world history.”

In Konya, Davutoğlu swung himself up to similar rhetorical heights when he declared, “This movement, which began in Khorasan with seeds sown and a Selçuk heritage shaped in Konya, has with the Ottomans become a world government and with it the Turkish Republic has gained a future.”

At the Nuremberg Rally in 1934, Adolf Hitler declared: “It is our wish and will that this state and this Reich shall endure in the millenniums to come. We can be happy in the knowledge that this future belongs to us completely.” As we know, this wish was short-lived, but this is perhapsa fact that Professor Davutoğlu has ignored in his study of the greater trajectory of world history.

The English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley put this succinctly in his poem “Ozymandias,” which tells of a traveler from an antique land who finds two vast and trunkless legs of stone standing in the desert. Nearby lies a shattered head with a “frown, and wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command” and a pedestal, on which is written: “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” As Shelley concludes: “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Robert Ellis is a regular commentator on Turkish affairs in the Danish and international press.