Erdogan used to rely on Turkey’s best and brightest—until he replaced them with its worst and dimmest.

By Durmus Yilmaz, Selim Sazak

| August 22, 2018, 5:44 PM

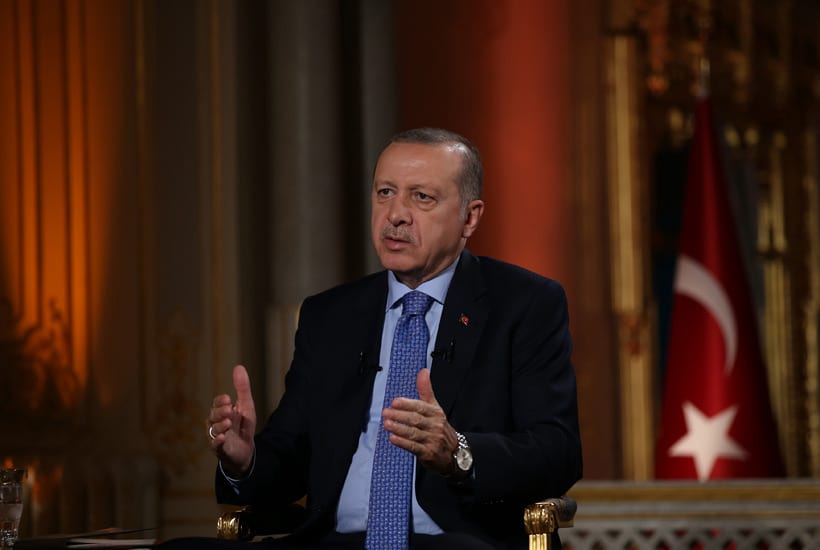

Recep Tayyip Erdogan holds with the president of Turkey’s Central Bank, Sureyya Serdengecti, a board featuring the new Turkish lira samples 25 October 2004 while Economy Minister Ali Babacan shows new coins during their presentation at central bank headquarters in the capital Ankara. (TARIK TINAZAY/AFP/Getty Images)

For most of the 2000s, Turkey was one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. The country’s ambitions soared even higher than its achievements: Ankara openly aspired to be the world’s 10th-largest market with a $2 trillion economy, exports reaching $500 billion, and a per capita income of $25,000. Every buzzword that global financial elites invented for their favorite combination of high-potential emerging markets—such as Goldman Sachs’s MINT and the Economist Intelligence Unit’s CIVETS—had a T for Turkey.

In the past month, the euphoria turned into anguish. The country plunged headfirst into an economic turmoil the likes of which it had not lived in a generation. Year to date, the lira lost almost 37 percent of its value against the dollar—around half of it during the roller coaster of the last month. Thirteen of the 35 Turks listed in Forbes’s list of the world’s wealthiest people have seen their fortunes fall below the billion mark. Turkish companies now hold more than $200 billion in debt, close to 10 percent of it due by the end of next year—much of it held by European banks. Spanish banks hold more than $80 billion in Turkish debt, French banks are owed close to $40 billion, and Italian banks about $20 billion. Turkey’s economic malaise can easily give Europe, and the entire global economy, a deadly flu.

Trending Articles

Erdogan Is Poised to Reform the Turkish Lira

Unfortunately for him, it probably won’t work.y

Many observers attribute these troubles to its president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and there is no denying that he is part of the problem. Crises of the kind Turkey is facing are especially prevalent under populist strongmen, whose growth fetish comes at the cost of higher inflation, artificially undervalued currency, poor fiscal discipline, and unresponsive monetary policies.

But to say that Erdogan is like other authoritarian leaders is to obscure the peculiarities of the Turkish story. Erdogan clearly subscribes to unorthodox economic theories—including an oft-repeated insistence that high-interest rates cause price inflation. But it’s only recently that such ignorance has had a tangible effect. If anything, Erdogan only managed to rise to unprecedented power because of his own earlier success at handling the economy. Before asking how bad Turkey’s economy will get, it’s important to understand where exactly it went wrong in the first place.

In 2002, Erdogan rose to power by riding the wave of discontent set off by the worst economic crisis in Turkey’s modern history. When he was elected prime minister, the biggest question was whether he would abandon the program put in place by Kemal Dervis, the World Bank economist and future U.N. development chief tasked with getting the country out of the ditch. Dervis was parachuted in to bring Ankara’s house in order. In typical fashion, he privatized state-owned enterprises, slashed budget deficits, toughened banking regulations, and abolished foreign exchange controls. His austerity policies earned plaudits abroad, but the IMF’s bitter pill crushed the backs of many at home.

In contrast, Erdogan was a protégé of Necmettin Erbakan, the Islamist ideologue who briefly served as prime minister in the early 1990s. Erbakan’s “just order” doctrine was a curious combination of Islamic conservatism and economic statism. Erbakan was an anti-capitalist: He championed interest-free banking and promoted state-led import substitution industrialization. (Although he was also an ardent anti-communist, as one would expect from a Cold War-era Islamist.) Many feared that Erdogan would adopt his mentor’s playbook, pausing and perhaps even undoing his predecessors’ reforms.

These fears did not come to pass. Erdogan continued the reform agenda to a tee. The credit for this smooth transition rested with his economic team in the early years. Most of them were economists by training. Many had studied or worked abroad. They were firmly committed to the orthodoxies of liberal economic thinking. They are also long since gone.

Erdogan’s decision-making in his earliest years in government was likely a product of political insecurity. Power had fallen into the lap of his Justice and Development Party (AKP) thanks to a quirk of Turkey’s electoral system, which requires parties to receive at least 10 percent of the ballots cast. In the 2002 election, the AKP won only one-third of the vote. (Factoring in the turnout rate, only a quarter of eligible voters had cast their ballot for Erdogan.) Yet the party received two-thirds of the parliament seats, because only two parties cleared the threshold.

Erdogan and his political advisors knew full well that if they were to remain in office, they had to convert their luck into practical success. Good governance was crucial not only for the country’s security and stability but also for the longevity and legitimacy of its new leaders. Here lay the secret of the AKP’s early success: sound policies, stable leadership, and skilled personnel.

The administration’s outward-looking face was Abdullah Gul, then one of Erdogan’s closest confidants. As a trained economist who had spent nearly a decade at the Islamic Development Bank before entering politics, Gul had a keen grasp of how the global economy worked. The U.S.-trained economy minister Ali Babacan and the Merrill Lynch banker-turned-finance minister Mehmet Simsek were his protégés, and much of the praise for Turkey’s economic miracle lay with them.

Read More

How a dispute over a jailed American pastor roiled Turkey’s economy.|

Colum Lynch, Robbie Gramer, Lara Seligman

Some of the problems that have since grown chronic were apparent even then. For example, Deputy Prime Minister Abdullatif Sener, a professor-turned-bureaucrat who was Erbakan’s finance minister in the mid-1990s and one of the AKP’s co-founders, resigned in 2009 after publicly accusing Erdogan of corruption; he is now a member of the opposition. Generally speaking, however, Erdogan understood the importance of both economic growth and stability and went to great lengths to build and keep investor confidence.

Leaders of the Central Bank, for example, were generally promoted from within the institution itself. The co-author of this article, who was the governor from 2006 to 2011, was educated in the United Kingdom and picked for the post after a 26-year career at the bank. The same held true for both his predecessor, Sureyya Serdengecti, a U.S.-educated bank veteran who was a holdover from Dervis’s team, and his replacement, Erdem Basci, a Johns Hopkins-educated economics professor. Even then, Erdogan rarely shied away from speaking his mind. Not until recently, however, were the independence and the competence of the bank’s leadership ever doubted.

Such days are now a distant memory—and the shift occurred at precisely the worst time. In the 2000s, cheap credit deluged emerging markets. The reforms Turkey had to undertake to pull itself out of the economic crisis of the early 2000s proved to be a blessing in disguise, in that it made Turkey a haven for foreign investors. Also adding to this enthusiasm were Turkey’s soaring ambitions to join the European Union, which, if realized, would have made the country into an economic powerhouse in the eurozone. Had Ankara been wiser, it could have ridden this wave to foster innovation, improve productivity, increase competitiveness, and invest in high-value-added and knowledge-based enterprises. Instead, the cheap credit went to government giveaways, crony contracts, pork barrel projects, and conspicuous consumption, for which Turks have no one but themselves to blame.

But once the global financial crisis struck and cheap credit started to dry up, these technocrats tried to warn him, if belatedly, of the importance of changing course. “If you speak the truth, have a foot in the stirrup,” goes a Turkish proverb—because those speaking truth to power quickly wear out their welcome. Even those at the highest echelons of government, such as Babacan and Simsek, warned publicly and repeatedly that Turkey needed to reduce private sector debt, restore rule of law, restrain credit-fueled consumption, and cool down the overheating economy. All these Cassandraesque warnings, however, fell on deaf ears. Those voicing them were shown out.

Once Turkey exited IMF supervision and his own powers started reaching new heights in the late 2000s, Erdogan started worrying less about playing by the book. As Turkey kept growing, so did Erdogan’s political fortunes. As growth fetishism replaced good governance, technocrats made way for loyalists. The economic portfolio, which was once divided among three ministries, is now in the hands of one person, former Energy Minister Berat Albayrak, whose primary qualification for the job seems to be his marriage to Erdogan’s daughter. The advice Erdogan receives comes not from bankers and technocrats but rather from shock-jock media personalities, such as Yigit Bulut and Cemil Ertem, who have little to offer other than their unwavering fealty.

Bulut is a particularly colorful figure. An ardent opponent-turned-diehard supporter, he is pushing some of the most bizarre and outlandish conspiracy theories and pseudoscience out of Ankara. Among his previous theories are that foreign chefs are spies, that the anti-government demonstrations of 2013 were incited by the German airline Lufthansa, and that Erdogan’s rivals have tried to kill him with telekinesis. In July, as Turkey’s troubles worsened, his televised diatribe accusing of treason the experts warning of an imminent currency meltdown quickly went viral. According to Bulut, the exchange rates were never going to weaken past 5 liras to a dollar. The dollar now trades at more than 6.

The fact that Turkey’s best and brightest have made way for its worst and dimmest perfectly embodies the essence of the country’s malaise. At every level of society, loyalty has replaced merit as the sole criterion. Corruption and cronyism are eating the country away like cancer. From schools to courts to markets to media, there is not a single area where the decay is not apparent. Polarization has reached such heights that nothing seems to be enough to bring Turks together, even for a shared moment of grief or triumph.

When one lacks the competence to deal with the challenges the country is facing, the common sense to reach out to those who do, and the courage to hear the inconvenient truths they would tell, all one is left with is denial, deceit, and conceit. A culture of impunity pervades the government: Nothing is ever wrong, and no one is ever responsible. The problem with such a culture is that facts don’t just disappear because one wants them to. Ankara is right in blaming Turkey’s troubles on its enemies, but it misses a crucial point: Turkey is its own worst enemy.

It is still not too late for Turkey. All that is needed is a return to reality: develop policies on facts, not fantasy; seek not the lies you want but the truths you need; hire the best and brightest, let them do their jobs, and stand behind them when they do. None of this is difficult. Anyone who wants to do it, can. The problem is that those in Ankara don’t seem like they do.

Durmus Yilmaz was the governor of the Central Bank of Turkey from 2006 to 2011. Since 2015, he has been serving as a member of parliament. He is currently the vice chair of Iyi Party, the centrist opposition party.

Selim Sazak is a doctoral student in political science at Brown University. @scsazak

View

Comments

Tags: Argument, Economics, Middle East, Politics, Turkey