By Dexter Filkins

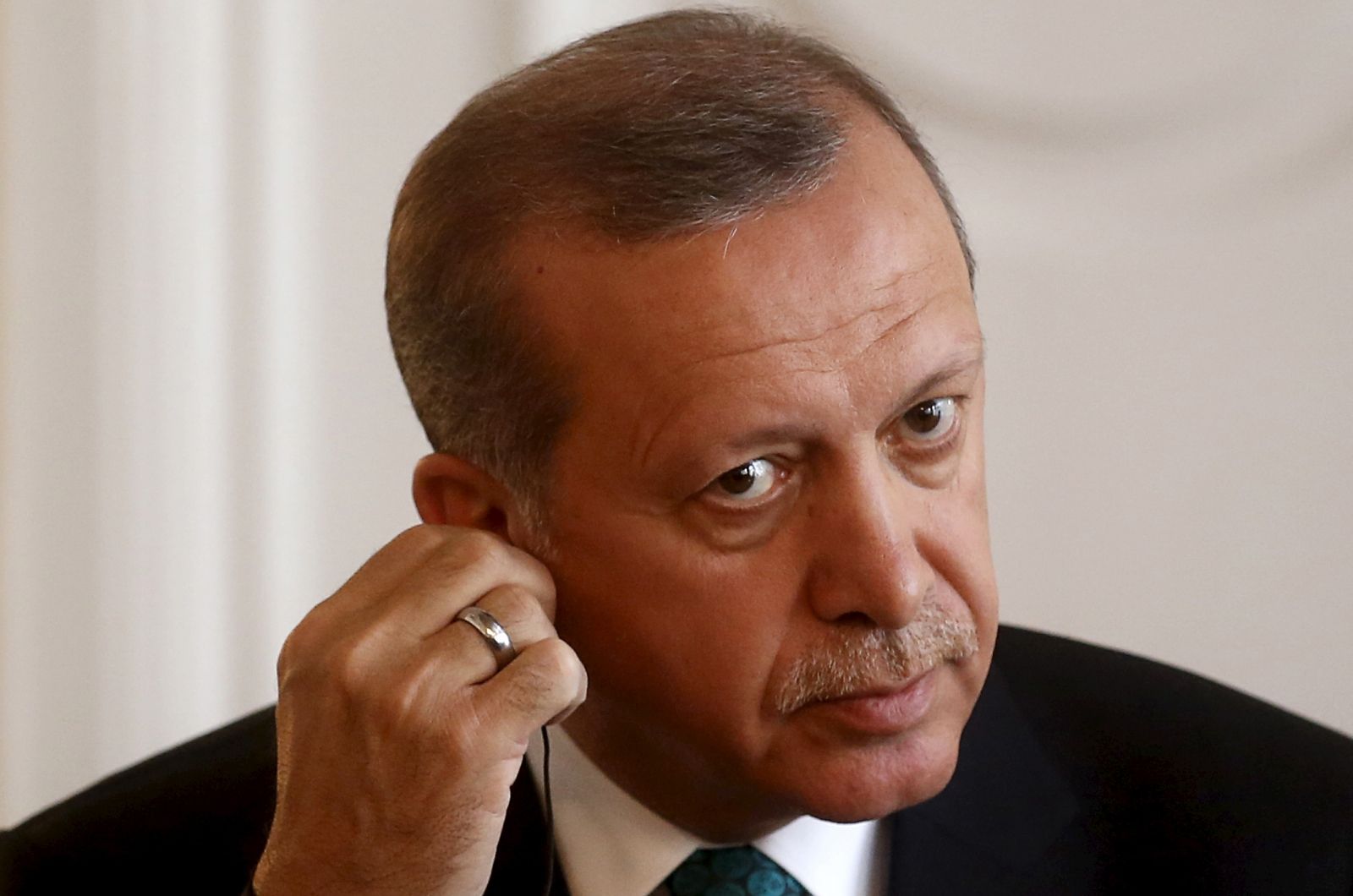

President Erdoğan’s plans to re-write the Turkish constitution are at a standstill after his Justice and Development Party failed to win a majority of seats in the general elections. Credit PHOTOGRAPH BY LEFTERIS PITARAKIS/AP

Whether abroad or at home, it’s easy to get disheartened by democracy: sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. But every now and then a moment arrives that wipes away our doubts and reaffirms our hopes in the wisdom of the democratic idea. One such moment came yesterday in Turkey, where voters decisively turned back President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s march to authoritarian rule.

For years, Erdoğan seemed unstoppable. First elected Prime Minister in 2003, Erdoğan came to power as a moderate Islamist reformer who overturned decades of rule by an unresponsive secular élite that, backed by the military, had dominated the Turkish Republic since its founding, in 1923. In his first years in office, Erdoğan did indeed act as the reformer he claimed to be. He liberalized the economy, granted new rights to Turkey’s long-suppressed Kurdish minority, and, most of all, gave voice to the majority: moderately religious Turks who wanted a greater say in the way the country was governed. During those years, Erdoğan was seen as the great hope of the Islamic world, the moderate Islamist who could bridge the divide with the West. Under Erdoğan, Turkey seemed to be a reasonable candidate to join the European Union.

Erdoğan dashed those hopes—slowly at first, and then, increasingly, in bombastic and megalomaniacal fashion. Beginning in 2007, he launched an extraordinary campaign to crush the secular-liberal-military establishment that formed the opposition. Prosecutors targeted generals, police officers, politicians, university professors, newspaper editors—anyone who represented a threat to the new Islamist order. The campaign made use of make-believe conspiracies with names like “Ergenekon’’ and “Sledgehammer,’’ which Erdoğan and his cronies claimed were aimed at taking over the country. More than seven hundred people were charged in these conspiracies, and many went to prison, despite the fact that even a cursory examination of the evidence showed that it was largely fabricated.

The most egregious illustration of Erdoğan’s authoritarianism was his government’s jailing of journalists. In 2012, ninety-four reporters and editors were in prison in Turkey, more than anywhere else in the world. (After widespread condemnation, the number has fallen to seven, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.)

As he grew stronger, Erdoğan constructed a cult of personality about himself, which made him stronger still. He dominated the news, often appearing on television several times a day, commenting on or inserting himself into seemingly every question in public life. He denounced Israel, and often made surreal comments about Jews and Jewish conspiracies. His assertive foreign policy, aimed at supporting the Islamist parties that emerged in the early Arab Spring, seemed to revive, for many Turks, the glory days of the Ottoman Empire. He began to build a third bridge across the Bosporus, and started construction on a new airport, planned to be the world’s largest, which he named after himself.

Despite the excesses, Erdoğan kept rising. After two terms as Prime Minister, he was, in 2014, elected President; and though on paper the new job had less power than his old one, it was widely understood that Erdoğan was in charge and that his Prime Minister, Ahmet Davutoğlu, was a mere satrap.* He told Turkish women to have at least three children, declaring that their “delicate nature” rendered them unequal to men. He threatened to ban Facebook and briefly banned Twitter, the latter after people posted wiretaps of conversations that appeared to reference corrupt activities.

The pièce de résistance was the new Presidential palace, which was completed last year and is now Erdoğan’s home. It’s fit for a monarch: it has a thousand rooms, cost $600 million, and employs five full-time food testers, who make sure Erdoğan’s food is not poisoned.

The turn against Erdoğan began on a small plot of land in central Istanbul called Gezi Park. In 2013, Erdoğan announced plans to replace the park with a shopping mall and a monument to Turkey’s Ottoman past. People gathered in the park to protest the decision, but the demonstrations grew rapidly into a broad protest against Erdoğan’s autocratic style, with gatherings in ninety cities. Erdoğan dismissed the demonstrators, who numbered in the hundreds of thousands, as a “few looters,’’ and then turned loose the police in Gezi Park. When the demonstrators were finally dispersed, eleven of them were dead and thousands had been injured or arrested. Among other things, the move dashed any hopes of getting Turkey into the European Union anytime soon.

Then, in December 2013, three members of Erdoğan’s cabinet, whose sons were implicated in a corruption scandal, resigned, with one of them calling on Erdoğan himself to quit. When the lead prosecutor in the case began to target Erdogan’s son, the Prime Minister dismissed him, beginning a massive purge of police and prosecutors around the country who were believed to be disloyal.

Obviously oblivious to the growing dissatisfaction around him, Erdoğan made clear, as this year’s elections approached, that he wanted to re-write the constitution in order to gain more power for the Presidency. The changes that Erdoğan was proposing were not just troubling in their own right but they seemed to signal his desire to stay in power for a long time. Increasingly, his role model appeared to be that elected autocrat to the north, Vladimir Putin.

For now, Erdoğan appears stopped in his tracks. His party, Justice and Development, captured more seats in parliament than any other but fell short of a majority. That probably means Erdoğan’s party will be forced to form a coalition government. Most important, the momentum, and the votes, to remake the constitution are no longer there.

The Turkish experience with coalition governments is not a happy one, and Turkey may be entering a period of instability, on which Erdoğan would be only too happy to capitalize. But for now, the voters of Turkey deserve a salute. Their election is gratifying enough to recall that famous maxim of democratic rule: “You can fool all of the people some of the time, and some of the people all of the time. But you can’t fool all of the people all of the time.”

*Correction: This piece previously misidentified the year in which Erdoğan was elected President. It was 2014, not 2011, as originally stated.