From: Demirtas Bayar [[email protected]]

Dear Friends,

This article gives the general view of the American informed classes. What the underlying meaning of the article is that once the mutiny is suppressed there is now a greater danger that Erdogan will become even more of a tyrant dictator. One other editorial stated that he has become like Putin.

Demirtas Bayar

U.S. Finds Itself on Shakier Ground as Erdogan Confronts Mutiny

NYT – By DAVID E. SANGER – JULY 15, 2016

WASHINGTON — With all the crises in the Middle East, the Obama administration took solace in the fact that there was one reliable, democratically elected strongman — a stalwart member of NATO — that Washington could depend on: President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey.

No matter how the coup attempt against Mr. Erdogan plays out over the next hours and days, that certainty is shattered.

Until midafternoon Friday, American officials thought Mr. Erdogan had tightened his iron grip on his country. He had purged the judiciary; jailed insouciant senior military officers three years ago and installed seemingly compliant successors; and cracked down on the opposition and the news media.

As one senior American diplomat said Friday evening, no one had come to work that day at the White House, the State Department or the C.I.A. expecting to see Mr. Erdogan turn to FaceTime on his iPhone to plead with the Turkish people to take to the streets in his defense.

Even though the coup attempt appeared to be failing by early Saturday morning in Turkey, the country had suddenly become another tumultuous one in a region that knows no end of turmoil.

Mr. Erdogan would almost certainly have to begin a purge of the plotters and probably hunt for other challengers to his authority — extending a streak of ruthlessness that has left many of his NATO allies gasping.

Friday’s events could leave in limbo some of the top priorities of the United States and Europe. They rely on Turkey to help battle the Islamic State, to contain the flow of migrants out of Syria, and to host American intelligence agencies and NATO forces seeking to grapple with upheaval in the Middle East.

The coup attempt “presents a dilemma to the United States and European governments: Do you support a nondemocratic coup,” or an “increasingly nondemocratic leader?” said Richard N. Haass, the president of the Council on Foreign Relations, where Mr. Erdogan has often come to talk with Americans influential in the relationship between the two countries.

To many in Washington, that dilemma is secondary to the question of whether Turkey will be a reliable partner in the battle against the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, a willing host to American forces and a stable player in the world’s most volatile corner.

American officials say the next 24 to 48 hours will be crucial in determining whether the coup attempt will have lasting repercussions. Unlike past bloodless coups in Turkey, this one does not have the implicitly understood support of the public, which appears to be divided over the military intervention.

“The danger here is this could spiral out of control and turn into a full-blown civil war,” Eric S. Edelman, a former American ambassador to Turkey and former leading Pentagon official under President George W. Bush, said in a telephone interview on Friday.

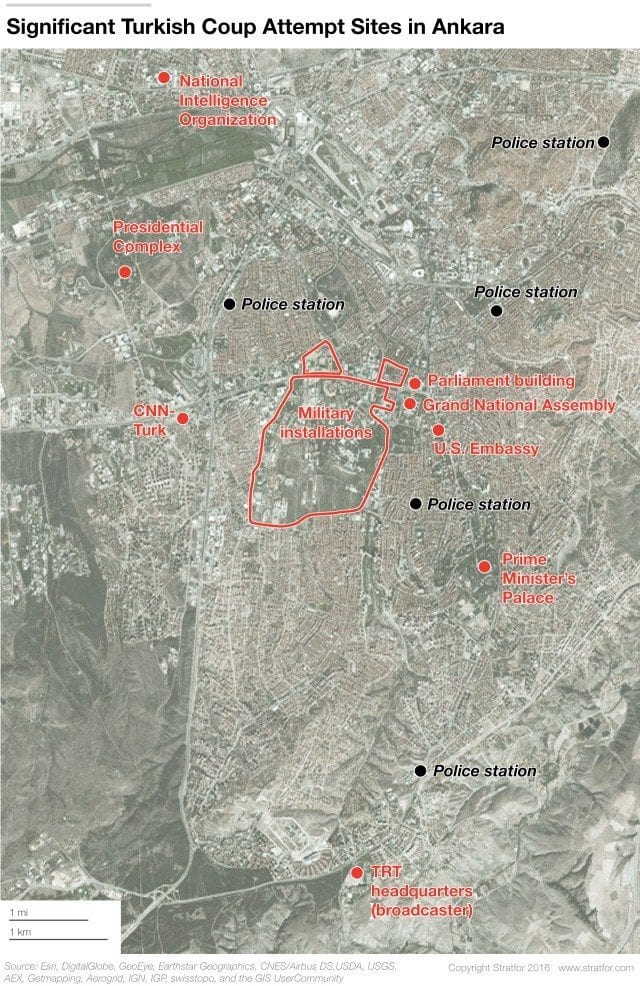

A military that appeared, on the surface, to be largely under the thumb of Mr. Erdogan is clearly riven with divisions so severe that the chief of staff appears to have been be detained while lower-level officers put tanks on the streets of Istanbul and the air force over Ankara, the capital.

Mr. Erdogan has plenty of enemies, eager to see him weakened or removed from power. Among them are Egypt’s president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who took power in a coup three years ago. The Russians, led by President Vladimir V. Putin, have tense relations with Mr. Erdogan, who has helped try to depose President Bashar al-Assad of Syria. And Mr. Assad himself would likely be both pleased and amazed if he held onto power longer than Mr. Erdogan.

Europeans would have plenty to worry about: Just a few months ago they struck a deal with Mr. Erdogan, paying Turkey more than $6 billion to hold onto Syrian migrants rather than let them flow into Western Europe, where many others had settled. It was the migrant crisis more than anything else, the Europeans believe, that led to Britain’s decision to exit the European Union. A failure to stem the flow, they feared, could lead to the breakup of Europe — a fear that American officials, led by Secretary of State John Kerry, shared.

Of the many intelligence failures that surrounded the Arab Spring uprisings five years ago, the coup in Turkey may soon be added to the list. A senior administration official who deals with Middle Eastern issues said that American diplomats and intelligence agencies were, before Friday, near unanimous in their view that a coup attempt was highly unlikely there.

Mr. Erdogan, in their view, was secure, the official said, bemoaning the state of American intelligence gathering in Turkey. In fact, diplomatic cables and intelligence reports written as recently as this month concluded that Mr. Erdogan had won enough support in the upper ranks of the military to head off any possible plots before they materialized, said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss intelligence reporting.

Officials will spend a lot of time determining what they missed. But as Cengiz Candar, a Turkey expert with Al-Monitor, an online news outlet, noted on Friday evening, Mr. Erdogan “made a Faustian bargain with the military, and now the military is back.”

“It was an alliance,” Mr. Candar said, “but the military is not his friend — not emotionally, not institutionally, not ideologically.”

Washington had its own problems with Mr. Erdogan and the crosscurrents of Turkish politics. Mr. Erdogan came to power a seeming reformist, and for a while the country seemed to be a flowering democracy. It was not too many years ago that Turkey was cited by many in the United States as a model for the Islamic world, a country that, like Indonesia, could find the right mix of moderate Islamism and democracy.

But for the past three years Mr. Erdogan’s crackdowns have become an increasing embarrassment to his NATO allies. His efforts to veer toward Islamism and crack down on the news media and opposition groups have left American officials caught between their instincts to support democracy and their reliance on an increasingly authoritarian leader.

The State Department human rights report, updated last month, complained about new laws allowing the government “to restrict freedom of expression, the press and the internet,” and the arrests of more than 30 journalists. It reported on arbitrary arrests and the denial of fair trials. It complained that Mr. Erdogan’s campaign against the Kurds, and the government’s fear of the Kurdish separatist movement, meant that one NATO ally was bombing rebel groups in Syria while the United States and others were funding — and depending — on those same groups.

Any prolonged instability in Turkey could impede Mr. Kerry’s latest effort to bring a cease-fire to Syria, and perhaps threaten the American ability to operate from the major air base at Incirlik, where many of the operations against the Islamic State are launched.