Title: Deadline for prequalification applications

Location: ANKARA

Description: Deadline for prequalification applications for

Meram and Aras electricity grid privatisation.

Date: 2008-07-18

Author: Aylin D. Miller

-

Deadline for prequalification applications

-

Deadline for bids for Izgas

Title: Deadline for bids for Izgas

Location: Izmit

Description: the gas distribution

network of the industrial city of Izmit.

Date: 2008-07-17 -

George Bush: “We thank brave Turkish police officers”

George Bush: “We thank brave Turkish police officers”[ 11 Jul 2008 19:01 ]

Ankara –APA. US President George Bush phoned to his Turkish counterpart Abdullah Gul and expressed condolences on the death of three police officers during a terrorist attack against the US Consulate General in Istanbul.

According to APA, Bush thanked Turkish government for the measures taken for the security of US Consulate, press-service of the Turkish President said. US President expressed condolences on behalf of American people to the families of killed police officers. He asked Abdullah Gul to deliver his condolences to the families of police officers. The presidents spoke about some regional issues too.

-

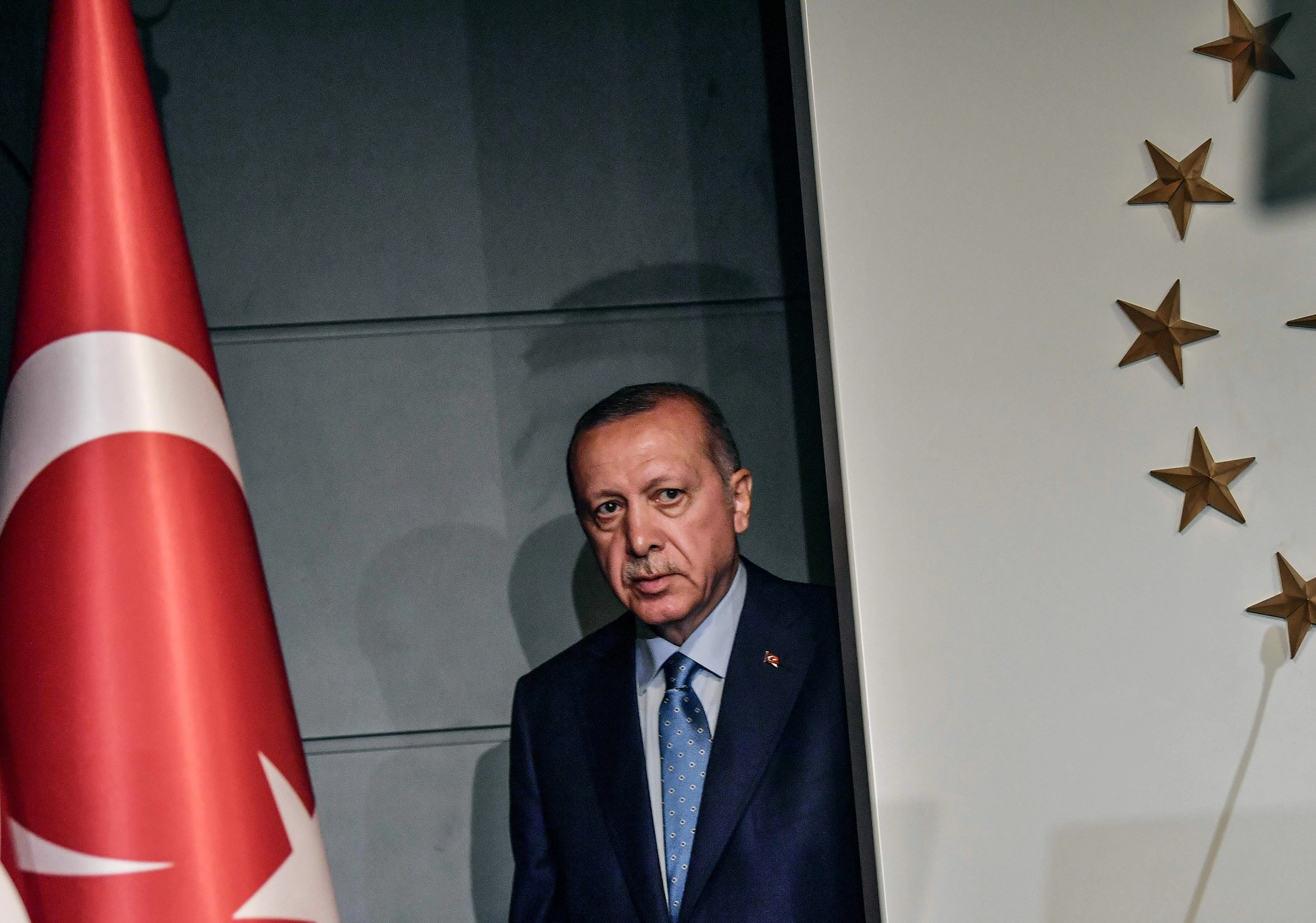

ERDOGAN PAYS FIRST OFFICIAL VISIT TO IRAQ

ERDOGAN PAYS FIRST OFFICIAL VISIT TO IRAQ

By Gareth Jenkins

Friday, July 11, 2008

On July 10 Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan arrived in Baghdad in the first official visit to Iraq by a Turkish head of government since 1990 and only the second by a regional leader since the U.S. invasion and occupation of the country in 2003.Speaking at a joint press conference with Erdogan in Baghdad, Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki described it as an “historic visit” and announced that: “The time is right for Turkey and Iraq to have developed relations” (Anatolian News Agency, July 10).

The composition of the delegation accompanying Erdogan was an indication of how Turkey hopes to underpin closer ties with Iraq by strengthening economic ties, through both bilateral trade and cooperation in energy. In addition to Foreign Minister Ali Babacan and Deputy Prime Minister Cemil Cicek, Erdogan was joined by Foreign Trade Minister Kursat Tuzmen and Energy Minister Hilmi Guler.

Erdogan and al-Maliki signed an agreement to create the institutional framework for closer ties between the two countries through the establishment of a Supreme Council for Strategic Cooperation. The council will be chaired by the two countries’ prime ministers and its work coordinated by their foreign ministers. A joint statement released by Turkey and Iraq explained that: “The ministers of energy, trade, investment, security and water resources will become members of the council; and the heads of the two governments can decide to expand the council so that ministers and officials in certain areas can join the council to develop bilateral cooperation to cover those areas” (Anatolian News Agency, July 10).

There is little doubt that Turkey’s most pressing issue, for which it wants closer strategic cooperation with Iraq, is an effective policy to eradicate the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) from northern Iraq.

In his statement at the joint press conference, Erdogan declared: “The PKK is the enemy not just of Turkey but of Iraq. Eradicating the PKK is one of the most important, and most serious, issues facing the two countries. Removing this organization from the agenda is to the advantage and benefit of both countries” (CNNTurk, July 10).

Erdogan expressed his gratitude for the support and understanding Turkey had received for its struggle against the PKK, not only from the central government in Baghdad but also from what he described as the “local Kurdish administration,” namely, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), which administers the predominantly Kurdish north of Iraq.

Even if Erdogan refrained from describing the KRG by the name used by most of the rest of the world, the fact that he publicly thanked the Iraqi Kurds at all is a further indication of a shift in Turkish policy away from confrontation and threats to conciliation and engagement toward the KRG.

Privately, Turkish military and civilian officials remain adamant that the Iraqi Kurds have yet to take sufficient measures to clamp down on the activities of the PKK in the lowlands of northern Iraq and isolate them in their camps and bases in the mountains. There is now, however, a general consensus in both the military and the civilian government in Turkey that engagement with the Iraqi Kurds is likely to produce better results than threatening economic sanctions and flexing its military muscles. But there is also an awareness that if Turkey engages directly with the KRG and sends delegations to the KRG capital of Arbil in northern Iraq, the Iraqi Kurds might interpret this as de facto recognition of their political authority in the north of the country and push ahead with their dreams of eventually establishing a full-fledged independent state; something that Turkey fears could further fuel separatist aspirations among its own restive Kurdish minority. As a result, Turkey appears likely to pursue a policy that combines conciliatory rhetoric with an increase in low-level contacts with Iraqi Kurdish officials, preferably outside the territory controlled by the KRG, for example, at meetings in Baghdad.

It is not only Turkey that is faced with a dilemma. The KRG is aware that even if they do not actively support the PKK, many Iraqi Kurds still feel a degree of empathy toward the organization. The KRG’s already precarious domestic popularity could suffer if it cracked down on the PKK at the behest of what many Iraqi Kurds regard as an aggressive foreign power. That might be seen as the KRG repressing fellow Kurds within its own borders, with nothing, such as political recognition, to show in return.

There are also concerns about the longevity of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), which is widely expected to be outlawed by the Turkish Constitutional Court in late summer or early fall; a decision that would probably trigger an early general election. The danger for the KRG is that if it cracks down on the PKK now, any policy of conciliation and engagement applied by the AKP could fall victim to nationalist rhetoric during an election campaign in Turkey and that the election could even result in the formation of a government that pursues a more hostile policy toward the KRG.

“We are ready to dance with Turkey, but we don’t know how many people we will end up dancing with,” said a KRG official (Posta, July 10).

-

Deadly Precedents in Kabul

July 9, 2008

By Fred Burton and Scott StewartA July 7 attack on the Indian Embassy in the Afghan capital of Kabul that killed two high-level diplomats has all the signs of a targeted assassination versus a strike aimed at the building itself with the goal of incurring a high body count.

The morning of July 7, 2008, began normally enough at the Indian Embassy in Kabul. Afghan citizens began to queue up on the dusty street outside the fortified compound in hopes of obtaining a visa, while shopkeepers nearby offered refreshments, visa photos and other administrative services to the aspiring visa applicants. One by one, the Indian employees of the embassy began to arrive at work and pass through security checks at the gate.

At around 8:30 a.m, as two embassy vehicles were in the process of entering the compound, the stillness of the morning was shattered when a suicide operative rammed his Toyota Corolla into the second of the two embassy vehicles and then activated the powerful improvised explosive device (IED) concealed in his car. The powerful blast destroyed the two embassy vehicles and blew the gates off the embassy’s outer perimeter. The blast killed at least 58 people and injured more than 140. Among those killed in the attack were two high-level diplomats: Indian Defense Attache Brig. Gen. Ravi Dutt Mehta and the embassy’s Political and Information Counselor, Vadapalli Venkateswara Rao. The blast also killed two Indo-Tibetan Border Police security officers, a local Afghan employee of the embassy and some 10 local police officers assigned to guard the facility. Several other Indian employees were injured in the attack, as were two foreign diplomats and several security personnel as signed to the adjacent Indonesian Embassy. Among those hit the hardest were the people standing in the visa line.

A Taliban spokesman, Zabiullah Mujahid, denied that the group was involved in the attack. However, it is not uncommon for the Taliban to deny responsibility for attacks that kill a large number of civilians, as they did in the Feb. 17, 2008, suicide attack in Kandahar that killed more than 100 people. The use of a suicide operative in the attack is a clear indication that it was conducted by the Taliban or their al Qaeda brethren, and the fact that the attack was conducted in Kabul — where a non-Afghan would stand out — would make the Taliban the most likely suspects, though it is quite possible they had assistance from al Qaeda or Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI).

The explosive device was powerful, but it was not the type of very large device one would use in an earnest attempt to destroy a building. Due to the size of the device and the identity of the victims, it is quite possible that this attack was a targeted assassination attempt and not an effort to destroy the embassy itself. The attack was well-executed and effective, and there are several lessons that can be drawn from it.

Target Selection

The Indian Embassy is a logical target for the Taliban to strike for variety of reasons. Perhaps the most significant reason is the history of India’s involvement in Afghanistan. New Delhi has long sought close relationships with the government of Afghanistan as a way to encircle and pressure India’s rival Pakistan. To this end, India has been one of the largest international supporters of Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s government. The government of India was also heavily involved in supporting the Northern Alliance as it fought against the government of the Taliban — which was very much a creature of the Pakistani ISI. The Indian government saw support of the Northern Alliance as a way to keep a check on Pakistani influence in the region.

While a number of Taliban attacks in recent years have killed or injured Indian engineers and workers involved in Indian-financed reconstruction projects in Afghanistan, this is the first time an Indian diplomatic post has been the target of a large-scale attack, even though India maintains consulates inside Afghanistan in locations such as Jalalabad, Herat and Mazar-e-Sharif and even Kandahar.

While Monday’s attack was the first attack of this scale against an Indian diplomatic target in Afghanistan, small-scale attacks have occurred before. In December 2007, the Indian Consulate in Jalalabad was targeted by a small-scale attack when two small explosive devices were hurled at the building during the night. The consulate in Kandahar was targeted by a similar attack in October 2006, when a man threw two hand grenades at the building from a motorbike.

Another reason for the Taliban to target the Indians is the Kashmir issue. The Pakistani ISI has long been supportive of Kashmiri militant groups, groups which have demonstrated links to al Qaeda and the global jihadist network. The Taliban government in Afghanistan was also supportive of Kashmiri militant groups. This support was clearly reflected in events such as the 1999 hijacking of Air India flight 814, in which Kashmiri militants landed the aircraft in Kandahar and held the passengers until the Indian government agreed to release a group of the militants’ imprisoned colleagues. The prisoners included a Pakistani cleric named Maulana Masood Azhar, founder of the militant group Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), who had been arrested in Kashmir and imprisoned in India, and JeM operative Omar Saeed Sheik, who has been convicted in Pakistan and sentenced to death for his involvement in the murder of U.S. journalist Daniel Pearl. The Indian government claims that Taliban fighters have fought alongside Kashmiri militant groups, and this long history means that there is absolutely no love lost between the Taliban and the Indian government. Of course, the ISI, al Qaeda, and Kashmiri militant groups also have strong motives for attacking Indian interests in Afghanistan, and it is possible they were somehow involved.

In any event, the targeting of Indian interests appears to be part of a concerted effort. On July 8, a remotely detonated IED was discovered on a bus carrying a group of Indian construction workers to a road construction site in Afghanistan’s Nimroz province. There have been several Taliban attacks on Indian construction crews working to build roads in Nimroz province since the efforts began in 2004. These attacks include two suicide attacks this year, one in April the other in June, that resulted in the deaths of three Indians.

Soft Target?

One final reason that might help explain the targeting of the Indian Embassy is that, by nature of its location and construction, it is more vulnerable to an attack than the embassies of high-profile coalition countries like the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia. The embassy had very little standoff separating the building from the outer perimeter wall, and as we have previously discussed, the critical element in keeping a facility like an embassy safe from large vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs) is standoff — keeping the device far from the building.

Of course, the Indians realized the vulnerability of their facility and were concerned about recent intelligence indicating a possible attack. On May 27, the Indian Embassy sent out a security advisory to Indian citizens warning of suicide attacks and compound invasions directed against high-profile facilities in Kabul. Ironically, the advisory was signed by Brig. Gen. R.D. Mehta, the defense attache killed in the attack. In June, the U.S. Embassy also issued a Warden Message noting a threat to Afghan officials and coalition personnel in the greater Kabul area, but it was not as specific as the Indian warning.

Within the last month, security at the Indian Embassy had been augmented with the addition of a substantial sand-filled outer layer to its perimeter fence. Judging from the photos of the scene, the augmented wall performed fairly well, with most of the damage occurring to the gate — which was literally blown away — and the portion of the building adjacent to the gate. This is where more than a few feet of standoff distance would have been very helpful.

Since the days of castles and knights, gates have always been the most vulnerable area of a wall and a natural place to target an attack. In more recent years, we have seen attacks directed at the gates of hardened diplomatic facilities, such as the VBIED attacks against the U.S. Embassy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Nairobi, Kenya, in 1998, and the armed assault on the U.S. Consulate in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in December 2004.

Targeted Assassination?

In addition to being a target itself, the gate at a secure facility also serves as a choke point. Security procedures can also leave potential targets vulnerable to attack as the targets enter the facility, or as they wait outside for security to screen their vehicle prior to entry. Many larger facilities will have a secure sally port area inside the gate where vehicles are screened for explosive devices, but in a facility with very little standoff there is often not room for such an area, and vehicles are checked on the street prior to entering the gate.

During this time, the vehicles are vulnerable to attack. Because of this, motorcades transporting high-profile persons normally contact the facility by radio and ask to have the gate cleared so that they can enter quickly and avoid having to sit on the street where they are vulnerable. Such motorcades normally use vehicles that have been checked for explosive devices and then continuously watched to ensure no such device has been placed on or in the vehicle. This means that they do not need to stop to have their vehicles checked by security at the gate. That said, the gate is still a choke point along the route of the motorcade, and the vehicle is vulnerable to attack as it slows down to make the turn into the gate. This window of opportunity can be amplified if the gate personnel are not particularly on the ball and it takes them a bit of time to open the gate.

That the bombing occurred as a vehicle was entering the facility raises the possibility that the attack at the Indian Embassy was not directed at the facility in general, but was a specifically targeted assassination. Another factor that points in that direction is that the attack was conducted at 8:30 a.m. local time, when some of the first diplomats were arriving at the embassy, rather than later in the day when more of the embassy staff (including the ambassador) would have been present. Also, although the device was quite powerful, it was not really large enough to have taken down the embassy building. If the attackers were attempting to destroy the embassy, they would likely have planned to use a larger device like those used in VBIED attacks against similar targets in places like Iraq. And make no mistake, the Taliban has been consistently moving toward the al Qaeda in Iraq modus operandi over the past few years.

The possibility of a targeted attack is also raised when one considers that the individuals killed in the attack were two senior embassy officers — the defense attache, who by his very job is an intelligence officer, and the political counselor — a position often used as cover for a senior intelligence officer. Even if the political counselor in this case was not an intelligence officer, he might have been mistaken for one by the attackers. If the two regularly rode together to work on a predictable schedule (for a 9 a.m. Monday staff meeting, for example), they could have posed a very tempting target for a potential attacker.

Of course this could all be coincidence. The two senior diplomats killed could simply have been at the wrong place at the wrong time. The timing of the attack could have been because the morning rush hour provided the attackers an opportunity to get their VBIED past the roadblocks and to the target site. Also, the attackers could have chosen to attack a building with a smaller rather than a larger device to ensure they made it to the particular target since they were more concerned about symbolism than destruction. However, that seems to be a lot of chance, and an intentional assassination would seem to be more probable at this point.

Disturbing precedent

If the attack was a targeted assassination and not a series of coincidental events (or erroneous reports), it sets a dangerous precedent. First, the attack was very well-orchestrated. The plotters conducted their preoperational surveillance and planned their attack without detection (though the warning issued by the Indian Embassy last month could be evidence of an operational security leak). However, in spite of the warning, the attack team was able to gain the element of tactical surprise. They were also able to amass explosives, construct the VBIED and deliver it to the attack site on time and without detection. The device also functioned as intended, and the operative did not get cold feet and bail out on the operation. These steps are not as easy to successfully execute as they might seem, especially when one considers that the Indian Embassy is located in the heart of Kabul just down the street from, and in sight of, the Afghan Interior Ministry. Operating in the hea rt of Kabul is a far cry from pulling off an attack in a location such as Kandahar, where the population is either sympathetic to or afraid of the Taliban.But by its very nature, the Indian Embassy would be an easy site to conduct surveillance on. In addition to the aforementioned merchants in the vicinity (a perennial favorite cover for surveillance operatives), there was also the visa line itself. Standing in a visa line provides a wonderful opportunity to loiter in front of an embassy for a prolonged period of time — perhaps hours — in order to observe security, monitor the arrivals of VIPs and generally watch what happens there.

Unfortunately, in spite of the warning of a potential attack and the increased physical security at the embassy, it is unlikely that the Indian government employed countersurveillance teams around their embassy.

While physical security upgrades are important and necessary, they can result in a false sense of security. The bottom line is that if potential attackers are permitted to conduct surveillance, they will be able to find vulnerabilities in security measures and procedures. With the Taliban demonstrating the ability to conduct sophisticated attacks in Kabul, perhaps with al Qaeda or ISI assistance in this case, other potential targets would be well advised to implement robust countersurveillance programs and deny the Taliban operatives carte blanche to conduct surveillance.

www.stratfor.com

-

The New Era

July 9, 2008

By Peter ZeihanAs students of geopolitics, we at Stratfor tend not to get overexcited when this or that plan for regional peace is tabled. Many of the world’s conflicts are geographic in nature, and changes in government or policy only rarely supersede the hard topography that we see as the dominant sculptor of the international system. Island states tend to exist in tension with their continental neighbors. Two countries linked by flat arable land will struggle until one emerges dominant. Land-based empires will clash with maritime cultures, and so on.

Petit vs. Grand Geopolitic

But the grand geopolitic — the framework which rules the interactions of regions with one another — is not the only rule in play. There is also the petit geopolitic that occurs among minor players within a region. Think of the grand geopolitic as the rise and fall of massive powers — the onslaught of the Golden Horde, the imperial clash between England and France, the U.S.-Soviet Cold War. By contrast, think of the petit geopolitic as the smaller powers that swim alongside or within the larger trends — Serbia versus Croatia, Vietnam versus Cambodia, Nicaragua versus Honduras. The same geographic rules apply, just on a smaller scale, with the added complexity of the grand geopolitic as backdrop.

The Middle East is a region rife with petit geopolitics. Since the failure of the Ottoman Empire, the region has not hosted an indigenous grand player. Instead, the region serves as a battleground for extra-regional grand powers, all attempting to grind down the local (petit) players to better achieve their own aims. Normally, Stratfor looks at the region in that light: an endless parade of small players and local noise in an environment where most trends worth watching are those implanted and shaped by outside forces. No peace deals are easy, but in the Middle East they require agreement not just from local powers, but also from those grand players beyond the region. The result is, well, the Middle East we all know.

All the more notable, then, that a peace deal — and a locally crafted one at that — has moved from the realm of the improbable to not merely the possible, but perhaps even the imminent.

Israel and Syria are looking to bury the hatchet, somewhere in the Golan Heights most likely, and they are doing so for their own reasons. Israel has secured deals with Egypt and Jordan already, and the Palestinians — by splitting internally — have defeated themselves as a strategic threat. A deal with Syria would make Israel the most secure it has been in millennia.

Syria, poor and ruled by its insecure Alawite minority, needs a basis of legitimacy that resonates with the dominant Sunni population better than its current game plan: issuing a shrill shriek whenever the name “Israel” is mentioned. The Alawites believe there is no guarantee of support better than cash, and their largest and most reliable source of cash is in Lebanon. Getting Lebanon requires an end to Damascus’ regional isolation, and the agreement of Israel.

The outline of the deal, then, is surprisingly simple: Israel gains military security from a peace deal in exchange for supporting Syrian primacy in Lebanon. The only local loser would be the entity that poses an economic challenge (in Lebanon) to Syria, and a military challenge (in Lebanon) to Israel — to wit, Hezbollah.

Hezbollah, understandably, is more than a little perturbed by the prospect of this tightening noose. Syria is redirecting the flow of Sunni militants from Iraq to Lebanon, likely for use against Hezbollah. Damascus also is working with the exiled leadership of the Palestinian group Hamas as a gesture of goodwill to Israel. The French — looking for a post-de Gaulle diplomatic victory — are re-engaging the Syrians and, to get Damascus on board, are dangling everything from aid and trade deals with Europe to that long-sought stamp of international approval. Oil-rich Sunni Arab states, sensing an opportunity to weaken Shiite Hezbollah, are flooding petrodollars in bribes — that is, investments — into Syria to underwrite a deal with Israel.

While the deal is not yet a fait accompli, the pieces are falling into place quite rapidly. Normally we would not be so optimistic, but the hard decisions — on Israel surrendering the Golan Heights and Syria laying preparations for cutting Hezbollah down to size — have already been made. On July 11 the leaders of Israel and Syria will be attending the same event in Paris, and if the French know anything about flair, a handshake may well be on the agenda.

It isn’t exactly pretty — and certainly isn’t tidy — but peace really does appear to be breaking out in the Middle East.

A Spoiler-Free Environment

Remember, the deal must please not just the petit players, but the grand ones as well. At this point, those with any interest in disrupting the flow of events normally would step in and do what they could to rock the boat. That, however, is not happening this time around. All of the normal cast members in the Middle Eastern drama are either unwilling to play that game at present, or are otherwise occupied.

The country with the most to lose is Iran. A Syria at formal peace with Israel is a Syria that has minimal need for an alliance with Iran, as well as a Syria that has every interest in destroying Hezbollah’s military capabilities. (Never forget that while Hezbollah is Syrian-operated, it is Iranian-founded and -funded.) But using Hezbollah to scupper the Israeli-Syrian talks would come with a cost, and we are not simply highlighting a possible military confrontation between Israel and Iran.

Iran is involved in negotiations far more complex and profound than anything that currently occupies Israel and Syria. Tehran and Washington are attempting to forge an understanding about the future of Iraq. The United States wants an Iraq sufficiently strong to restore the balance of power in the Persian Gulf and thus prevent any Iranian military incursion into the oil fields of the Arabian Peninsula. Iran wants an Iraq that is sufficiently weak that it will never again be able to launch an attack on Persia. Such unflinching national interests are proving difficult to reconcile, but do not confuse “difficult” with “impossible” — the positions are not mutually exclusive. After all, while both want influence, neither demands domination.

Remarkable progress has been made during the past six months. The two sides have cooperated in bringing down violence in Iraq, now at its lowest level since the aftermath of the 2003 invasion itself. Washington and Tehran also have attacked the problems of rogue Shiite militias from both ends, most notably with the neutering of Muqtada al-Sadr and his militia, the Medhi Army. Meanwhile, that ever-enlarging pot of Sunni Arab oil money has been just as active in Baghdad in drawing various groups to the table as it has been in Damascus. Thus, while the U.S.-Iranian understanding is not final, formal or imminent, it is taking shape with remarkable speed. There are many ways it still could be derailed, but none would be so effective as Iran using Hezbollah to launch another war with Israel.

China and Russia both would like to see the Middle East off balance — if not on fire in the case of Russia — although it is hardly because they enjoy the bloodshed. Currently, the United States has the bulk of its ground forces loaded down with Afghan and Iraqi operations. So long as that remains the case — so long as Iran and the United States do not have a meeting of the minds — the United States lacks the military capability to deploy any large-scale ground forces anywhere else in the world. In the past, Moscow and Beijing have used weapons sales or energy deals to bolster Iran’s position, thus delaying any embryonic deal with Washington.

But such impediments are not being seeded now.

Rising inflation in China has turned the traditional question of the country’s shaky financial system on its head. Mass employment in China is made possible not by a sound economic structure, but by de facto subsidization via ultra-cheap loans. But such massive availability of credit has artificially spiked demand, for 1.3 billion people no less, creating an inflation nightmare that is difficult to solve. Cut the loans to rein in demand and inflation, and you cut business and with it employment. Chinese governments have been toppled by less. Beijing is desperate to keep one step ahead of either an inflationary spiral or a credit meltdown — and wants nothing more than for the Olympics to go off as hitch-free as possible. Tinkering with the Middle East is the furthest thing from Beijing’s preoccupied mind.

Meanwhile, Russia is still growing through its leadership “transition,” with the Kremlin power clans still going for each other’s throats. Their war for control of the defense and energy industries still rages, their war for control of the justice and legal systems is only now beginning to rage, and their efforts to curtail the powers of some of Russia’s more independent-minded republics such as Tatarstan has not yet begun to rage. Between a much-needed resettling, and some smacking of out-of-control egos, Russia still needs weeks (or months?) to get its own house in order. The Kremlin can still make small gestures — Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin chatted briefly by phone July 7 with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad on the topic of the nuclear power plant that Russia is building for Iran at Bushehr — but for the most part, the Middle East will have to wait for another day.

But by the time Beijing or Moscow have the freedom of movement to do anything, the Middle East may well be as “solved” as it can be.

The New Era

For those of us at Stratfor who have become rather inured to the agonies of the Middle East, such a sustained stream of constructive, positive news is somewhat unnerving. One gets the feeling that if the progress could hold up for just a touch longer, not only would there be an Israeli-Syrian deal and a U.S.-Iranian understanding, the world itself would change. Those of us here who are old enough to remember haven’t sensed such a fateful moment since the weeks before the tearing down of the Berlin Wall in 1989. And — odd though it may sound — we have been waiting for just such a moment for some time. Certainly since before 9/11.

Stratfor views the world as working in cycles. Powers or coalitions of powers form and do battle across the world. Their struggles define the eras through which humanity evolves, and those struggles tend to end in a military conflict that lays the groundwork for the next era. The Germans defeated Imperial France in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, giving rise to the German era. That era lasted until a coalition of powers crushed Germany in World Wars I and II. That victorious coalition split into the two sides of the Cold War until the West triumphed in 1989.

New eras do not form spontaneously. There is a brief — historically speaking — period between the sweeping away of the rules of the old era and the installation of the rules of the new. These interregnums tend to be very dangerous affairs, as the victorious powers attempt to entrench their victory as new powers rise to the fore — and as many petit powers, suddenly out from under the thumb of any grand power, try to carve out a niche for themselves.

The post-World War I interregnum witnessed the complete upending of Asian and European security structures. The post-World War II interregnum brought about the Korean War as China’s rise slammed into America’s efforts to entrench its power. The post-Cold War interregnum produced Yugoslav wars, a variety of conflicts in the former Soviet Union (most notably in Chechnya), the rise of al Qaeda, the jihadist conflict and the Iraq war.

All these conflicts are now well past their critical phases, and in most cases are already sewn up. All of the pieces of Yugoslavia are on the road to EU membership. Russia’s borderlands — while hardly bastions of glee — have settled. Terrorism may be very much alive, but al Qaeda as a strategic threat is very much not. Even the Iraq war is winding to a conclusion. Put simply, the Cold War interregnum is coming to a close and a new era is dawning.

www.stratfor.com