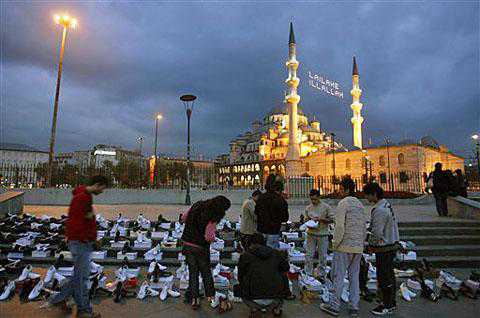

When twin bombings ripped through a busy square in Istanbul Sunday, some in Turkey blamed the militant Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) for the blasts. That renewed focus on the group doesn’t bode well for many Kurds abroad.

Citing security sources, CNN-Turk television said that intelligence reports suggested the group was planning a bombing campaign in Turkish cities.

Though the Firat news agency reported Monday that the PKK had denied responsibility for the blast — which killed 17 and injured more than 150, making it the worst in the city since 2003 — suspicions about Kurdish involvement still abound.

“There are signs of links to the separatist group,” Istanbul Governor Muammer Guler told reporters.

“Of course it’s the PKK,” Orhan Balci, a 38-year-old textile businessman from the area told Reuters news service. “This has nothing to do with politics, this is all about the PKK.”

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan on Monday could not be called out into naming the PKK as the culprits behind the pair of bombings saying only, “Turkey’s fight against terrorism will continue” and that “the terrorist group’s biggest aim is to make propaganda.”

Fears of a foray to western Turkey

Whether responsible or not, the rebel movement has been blamed for a number of events in Turkey since its inception in 1984. The most recent headline-making action before this weekend’s blast — the kidnapping and eventual release of three German climbers from the slopes of Mount Ararat — has led many to worry that the battle for an autonomous Kurdistan may spread into western Turkey.

This fear poses a special problem for Germany, which is home to one of the largest Turkish expatriate communities and provides shelter for more than half a million Kurds. Much of the fear and hostility felt toward ethnic Kurds in Turkey as a consequence of the PKK’s actions has long simmered among the immigrant population in Germany.

In November, demonstrations over Turkey’s foray into Kurdish territory in northern Iraq broke out in Berlin’s Neu-Koelln neighborhood and members of the Turkish nationalist “Gray Wolf” gang attacked people at a Kurdish culture center in the German capital. In February, the Berliner Zeitung reported on the bullying and harassment a 7-year-old Kurd received at school after wearing a scarf in the colors of Kurdistan.

“We’re trying to live in peace with the Turks,” Evrim Baba, a representative of the Kurdish community in Berlin told the newspaper.

“We want peace,” a young man named Achmed told DW-WORLD after the November attacks.

A community divided

That peace has proven difficult to attain. Even among members of the Kurdish community itself, there is disagreement about the PKK. Though Germany officially banned the PKK in 1993, many of the exiles here openly sympathize with the organization’s struggle to obtain an autonomous homeland in the triangular area of southern Turkey, northern Iraq, and northwest Iran.

“The Kurds have an incredible debt toward this organization,” Mahmut Seven, who runs the only Kurdish daily newspaper Yeni Özgür Politika, told the German newsmagazine Der Spiegel. “They gave us back our pride and our identity.”

Baktheyar Ibrahim, an Iraqi-Kurd who had to flee a well-paying government job in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, sees things another way. As a supporter of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan political party, he believes in the attainment of an independent Kurdistan through democratic processes. The group, which supports Iraqi President Jalal Talabani, often finds itself at odds with other organizations fighting for the same goals.

But the PKK has made things especially difficult for Ibrahim and for other exiles like him in recent months as Germany’s instituted a major crackdown on the Kurdish population to curb PKK sympathies.

Kurdish associations in Hannover, Kassel, Bremen, Koblenz and Berlin have all been raided by German security agencies and suspected members of the separatist movement taken into custody.

Roj TV, the sole Kurdish television station in the country, was banned last June, followed shortly by a ban on the production company Viko, which is located in the western Germany city of Wuppertal.

Citing political reforms in Turkey, the German government has carried out a number of asylum revocations, making the search for political refuge more difficult and angering moderate Kurds who don’t see the situation in Turkey as having improved.

“Go back to Turkey?” asked Mostafa, a 32-year-old refugee from Istanbul who’s since become a naturalized German. “For me, that’s impossible.”