The brown leather binding looks unremarkable enough, but within the Library’s rare books collection there is a volume, which once opened up, demonstrates a key turning point in the development of printing in the Islamic world. The volume is the ‘Cihannüma’ of Katip Celebi from the printing house of Ibrahim Müteferrika. It was printed in Istanbul in 1732, an example of a printed book from the very first Islamic printing house.

The introduction of printing in moveable type was slow to develop in the Middle East. The very earliest examples of printing in Arabic script date from early 16th century Europe, where religious texts were printed, especially by Italian printers. Some early Arabic religious texts were also printed from presses in Christian communities in the Middle East, but it was not until the early 18th century that printing in Arabic script by Islamic printing houses in the Islamic world was officially authorized.

The initiative came from a certain Said Efendi, son of the Ottoman Ambassador to Paris who accompanied his father on a diplomatic visit there in 1721. There he had learned about printing and on his return to Istanbul he requested the support of the Grand Vizier in the setting up of a printing press. His chief collaborator was Ibrahim Müteferrika, a man with many interests including astronomy, history, philosophy and theology. He was born in Hungary in 1674, probably a Christian who converted to Islam. The name ‘Müteferrika’ is derived from his employment as a bureaucrat and diplomat under Sultan Ahmed III.

Together with Said Efendi he was granted permission to print books in Ottoman Turkish in Arabic script. The presses and type fonts were obtained from local Jewish and Christian printers and later imported from Europe. Ibrahim Müteferrika became director of the first Turkish printing press. The first book, a dictionary, was printed in 1729. Religious texts were officially excluded as they continued to be copied in manuscript form only. There was a vested interest among the local scribes and calligraphers to prevent the growth of printing. The cursive design of Arabic script lent itself particularly well to manuscript production and the manuscript workshops presented a constant opposition to Müteferrika’s enterprise.

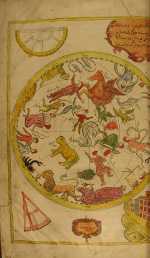

Important among his printed works was the world atlas, the ‘Cihannüma’ of Katip Celebi printed in 1732. This is a world atlas, or cosmography, loosely translated as ‘The mirror of the world’. Celebi (1609–1657) was an Ottoman historian, bibliographer and geographer and the most conspicuous and productive scholar, particularly in the non-religious sciences in the 17th-century Ottoman Empire. He was a life-long friend of Müteferrika.

The Library is fortunate to possess a single printed work from Müteferrika‘s press and it is a copy of this work (S828.a.73.2). The copy demonstrates a number of interesting features.

The design and layout of the first leaf of the text with red and black type looks exactly like the opening of a manuscript; the traditional ‘title page’ usual in the printed books had not yet been developed. Müteferrika has himself added a significant introduction to his printing of Celebi’s work in which he discusses the Copernican view of astronomy. He is considered to be one of the first people to introduce the Copernican view of the solar system to Ottoman readers.

The diagrams and maps within the volume, of which there are over forty, cover the countries of the Middle East, the Mediterranean and areas farther afield. Although the map outlines are printed, many have been coloured at a later date in a rather crude way with a brush in primary colours, giving the pages a primitive look. The book has also lost its original Islamic binding and was re-bound in a European style probably on its arrival in the Library. The binding is too tight and makes the text and illustrations in the central gutter difficult to read.

Back in Istanbul, however, the printing activities did not last and came to an end in 1743, due to strong opposition of the local scribes to Müteferrika’s enterprise. He died in 1745, after printing works on grammar, geography, maths and above all, history; books from his press are often known as the ‘Turkish incunabula’. But this change was not long-lasting and printing houses eventually grew up in other Middle Eastern cities. Eventually even the ban of printing religious texts was lifted and the first printed Qur’an texts appeared in the 1860s. So perhaps Ibrahim Müteferrika, the court official and printer from Istanbul, had started a quiet revolution.

via Special Collections » An Ottoman cosmography.

Leave a Reply