Exclusive: Secret apartheid-era papers give first official evidence of Israeli nuclear weapons

Chris McGreal in Washington

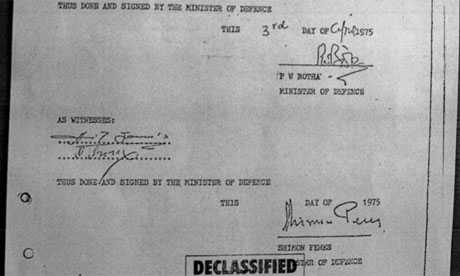

- The secret military agreement signed by Shimon Peres, now president of Israel, and P W Botha of South Africa. Photograph: Guardian

Secret South African documents reveal that Israel offered to sell nuclear warheads to the apartheid regime, providing the first official documentary evidence of the state’s possession of nuclear weapons.

The “top secret” minutes of meetings between senior officials from the two countries in 1975 show that South Africa‘s defence minister, PW Botha, asked for the warheads and Shimon Peres, then Israel’s defence minister and now its president, responded by offering them “in three sizes”. The two men also signed a broad-ranging agreement governing military ties between the two countries that included a clause declaring that “the very existence of this agreement” was to remain secret.

The documents, uncovered by an American academic, Sasha Polakow-Suransky, in research for a book on the close relationship between the two countries, provide evidence that Israel has nuclear weapons despite its policy of “ambiguity” in neither confirming nor denying their existence.

The Israeli authorities tried to stop South Africa’s post-apartheid government declassifying the documents at Polakow-Suransky’s request and the revelations will be an embarrassment, particularly as this week’s nuclear non-proliferation talks in New York focus on the Middle East.

They will also undermine Israel’s attempts to suggest that, if it has nuclear weapons, it is a “responsible” power that would not misuse them, whereas countries such as Iran cannot be trusted.

A spokeswoman for Peres today said the report was baseless and there were “never any negotiations” between the two countries. She did not comment on the authenticity of the documents.

South African documents show that the apartheid-era military wanted the missiles as a deterrent and for potential strikes against neighbouring states.

The documents show both sides met on 31 March 1975. Polakow-Suransky writes in his book published in the US this week, The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s secret alliance with apartheid South Africa. At the talks Israeli officials “formally offered to sell South Africa some of the nuclear-capable Jericho missiles in its arsenal”.

Among those attending the meeting was the South African military chief of staff, Lieutenant General RF Armstrong. He immediately drew up a memo in which he laid out the benefits of South Africa obtaining the Jericho missiles but only if they were fitted with nuclear weapons.

The memo, marked “top secret” and dated the same day as the meeting with the Israelis, has previously been revealed but its context was not fully understood because it was not known to be directly linked to the Israeli offer on the same day and that it was the basis for a direct request to Israel. In it, Armstrong writes: “In considering the merits of a weapon system such as the one being offered, certain assumptions have been made: a) That the missiles will be armed with nuclear warheads manufactured in RSA (Republic of South Africa) or acquired elsewhere.”

But South Africa was years from being able to build atomic weapons. A little more than two months later, on 4 June, Peres and Botha met in Zurich. By then the Jericho project had the codename Chalet.

The top secret minutes of the meeting record that: “Minister Botha expressed interest in a limited number of units of Chalet subject to the correct payload being available.” The document then records: “Minister Peres said the correct payload was available in three sizes. Minister Botha expressed his appreciation and said that he would ask for advice.” The “three sizes” are believed to refer to the conventional, chemical and nuclear weapons.

The use of a euphemism, the “correct payload”, reflects Israeli sensitivity over the nuclear issue and would not have been used had it been referring to conventional weapons. It can also only have meant nuclear warheads as Armstrong’s memorandum makes clear South Africa was interested in the Jericho missiles solely as a means of delivering nuclear weapons.

In addition, the only payload the South Africans would have needed to obtain from Israel was nuclear. The South Africans were capable of putting together other warheads.

Botha did not go ahead with the deal in part because of the cost. In addition, any deal would have to have had final approval by Israel’s prime minister and it is uncertain it would have been forthcoming.

South Africa eventually built its own nuclear bombs, albeit possibly with Israeli assistance. But the collaboration on military technology only grew over the following years. South Africa also provided much of the yellowcake uranium that Israel required to develop its weapons.

The documents confirm accounts by a former South African naval commander, Dieter Gerhardt – jailed in 1983 for spying for the Soviet Union. After his release with the collapse of apartheid, Gerhardt said there was an agreement between Israel and South Africa called Chalet which involved an offer by the Jewish state to arm eight Jericho missiles with “special warheads”. Gerhardt said these were atomic bombs. But until now there has been no documentary evidence of the offer.

Some weeks before Peres made his offer of nuclear warheads to Botha, the two defence ministers signed a covert agreement governing the military alliance known as Secment. It was so secret that it included a denial of its own existence: “It is hereby expressly agreed that the very existence of this agreement… shall be secret and shall not be disclosed by either party”.

The agreement also said that neither party could unilaterally renounce it.

The existence of Israel’s nuclear weapons programme was revealed by Mordechai Vanunu to the Sunday Times in 1986. He provided photographs taken inside the Dimona nuclear site and gave detailed descriptions of the processes involved in producing part of the nuclear material but provided no written documentation.

Documents seized by Iranian students from the US embassy in Tehran after the 1979 revolution revealed the Shah expressed an interest to Israel in developing nuclear arms. But the South African documents offer confirmation Israel was in a position to arm Jericho missiles with nuclear warheads.

Israel pressured the present South African government not to declassify documents obtained by Polakow-Suransky. “The Israeli defence ministry tried to block my access to the Secment agreement on the grounds it was sensitive material, especially the signature and the date,” he said. “The South Africans didn’t seem to care; they blacked out a few lines and handed it over to me. The ANC government is not so worried about protecting the dirty laundry of the apartheid regime’s old allies.”

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/may/23/israel-south-africa-nuclear-weapons

[2]

Israeli president denies offering nuclear weapons to apartheid South Africa

Shimon Peres dismisses claims relating to secret files but US researcher says denials are disingenuous

Chris McGreal in Washington, Rory McCarthy in Jerusalem and David Smith in Johannesburg

Israel‘s president, Shimon Peres, today robustly denied revelations in the Guardian and a new book that he offered to sell nuclear weapons to apartheid South Africa when he was defence minister in the 1970s.

His office said “there exists no basis in reality” for claims based on declassified secret South African documents that he offered nuclear warheads for sale with ballistic missiles to the apartheid regime in 1975. “Israel has never negotiated the exchange of nuclear weapons with South Africa. There exists no Israeli document or Israeli signature on a document that such negotiations took place,” it said.

But Sasha Polakow-Suransky, the American academic who uncovered the documents while researching a book on the military and political relationship between the two countries, said the denials were disingenuous, because the minutes of meetings Peres held with the then South African defence minister, PW Botha, show that the apartheid government believed an explicit offer to provide nuclear warheads had been made.

Polakow-Suransky noted that Peres did not deny attending the meetings at which the purchase of Israeli weapons systems, including ballistic missiles, was discussed. “Peres participated in high level discussions with the South African defence minister and led the South Africans to believe that an offer of nuclear Jerichos was on the table,” he said. “It’s clear from the documentary record that the South Africans perceived that an explicit offer was on the table. Four days later Peres signed a secrecy agreement with PW Botha.”

While Peres’s office said there are no documents with his signature on that mention nuclear weapons, his signature does appear with Botha’s on an agreement governing the broad conduct of the military relationship, including a commitment to keep it secret.

Today politicians and academics in South Africa said the apartheid regime’s cooperation with Israel was an “open secret” and they welcomed the current government’s move to declassify sensitive documents which provided details of key meetings.

Steven Friedman, the director of Centre for the Study of Democracy at Rhodes University and the University of Johannesburg, said: “There was a close cooperation on a range of issues. In the 1970s and 1980s there was a sudden influx of Israeli nuclear scientists. We knew there was extensive military cooperation.”

Professor Willie Esterhuyse, who played a critical role in opening and maintaining dialogue between the apartheid government and the ANC, said: “Most of us knew there was close cooperation on nuclear research with not just Israel but also the French. But we had no factual evidence. We eventually figured out it was more than just rumours, but we never knew the precise details.”

Opposition politicians praised the post-apartheid government for resisting attempts by the Israeli authorities to prevent the documents from becoming public. David Maynier, the shadow defence minister, speculated that the ANC government had decided it would not be damaged by releasing the documents.

“It did not take me entirely by surprise, because I think it was a pretty open secret there was extensive cooperation between South Africa and Israel. But before now the details were super-secret,” he said.

The South African documents obtained by Polakow-Suransky and published in today’s Guardian, include “top secret” South African minutes of meetings between senior officials from the two countries as well as direct negotiations in Zurich between Peres and Botha.

The South African military chief of staff, Lieutenant General RF Armstrong, who attended the meetings, drew up a memo laying out the benefits of South Africa obtaining the Israeli missiles – but only if they were fitted with nuclear weapons.

Polakow-Suransky said the minutes record that at the meeting in Zurich on 4 June 1975, Botha asked Peres about obtaining Jericho missiles, codenamed Chalet, with nuclear warheads.

“Minister Botha expressed interest in a limited number of units of Chalet subject to the correct payload being available,” the minutes said. The document then records that: “Minister Peres said that the correct payload was available in three sizes”.

The use of a euphemism, the “correct payload”, reflects Israeli sensitivity over the nuclear issue. Armstrong’s memorandum makes clear the South Africans were interested in the Jericho missiles solely as a means of delivering nuclear weapons.

The use of euphemisms in a document that otherwise speaks openly about conventional weapons systems also points to the discussion of nuclear weapons.

In the end, South Africa did not buy nuclear warheads from Israel and eventually developed its own atom bomb.

The Israeli authorities tried to prevent South Africa’s post-apartheid government from declassifying the documents.

Peres’s angry response to the revelations is unusual, because of Israel’s policy of maintaining “ambiguity” about whether it possesses nuclear weapons. The Israeli press quoted anonymous government officials challenging the truth of the documents.

Polakow-Suransky said it is possible Peres made the offer without the approval of Israel’s then prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin. “Peres has a long history of conducting his own independent foreign policy. During the 1950s as Israel was building its defence relationship with France, Peres went behind the back of many of his superiors in initiating talks with French defence officials. It would not be surprising if he broached the topic in discussions with South Africa’s defence minister without Rabin’s authorisation,” he said.

Polakow-Suransky’s book, The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa, is published in the US on Tuesday.

Politician at heart of Israel

Shimon Peres, the man at centre of allegations over nuclear links with apartheid South Africa, has spent decades in government in various cabinet posts, including defence and foreign, as prime minister and now as Israel’s president.

Born in Poland in 1923, he and his family moved to Palestine under the British mandate when he was 11. Many of his relatives were murdered in the Holocaust.

In 1947, he joined the Haganah, the Jewish force fighting for Israeli independence. He was placed in charge of personnel and arms purchases.

He Peres rose quickly through the political world in the years immediately after independence, becoming Ddirector general, at 30, of the defence ministry. In the following years, he played a leading role in building strategic alliances and developing arms deals. One of the most important early on was with France, which played a crucial role in the development of Israel’s nuclear programme. Later, as relations with Paris cooled, he was at the forefront of building links with apartheid South Africa.

Peres was first elected to the Knesset in 1959. He persistently challenged Yitzhak Rabin for the Labour party leadership, only becoming leader in 1977 after Rabin was forced out over his wife’s illegal foreign bank account. He became the unofficial acting prime minister but lost the subsequent general election.

Peres, as foreign minister, won the Nobel peace prize in 1994 with Rabin and Yasser Arafat for the negotiations that produced the Oslo accords.

After Rabin’s assassination in 1995, he became PM and lost the subsequent election. In 2005, he quit Labour to back Ariel Sharon’s new Kadima party. Two years later, the Knesset elected Peres president. Peres married Sonya Gelman in 1945. They have three children.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/may/24/israel-shimon-peres-nuclear-weapons

The Guardian, 24 May 2010

Leave a Reply