Unlike the trenches of the Western Front, plowed under by farmers soon after the war, Gallipoli’s trench system remained largely intact after the battle. “It’s so barren and bleak, nobody ever wanted to occupy it,” says Richard Reid, an Australian Department of Veterans Affairs historian working on the project. But erosion caused by wind and rain, as well as the increasing popularity of the battlefield among both Turkish and foreign tourists, now threaten to destroy these last remaining traces. “In a few more years, you won’t be able to see any of the trenches, but at least you’ll have a record of exactly where they were,” says Ian McGibbon, a New Zealand military historian who estimates that he’s spent a total of 100 days here since 2010.

The researchers have marked nine miles of frontline trenches, communications trenches and tunnels burrowed by the antagonists several dozen feet beneath each other’s positions in an effort to blow them up from below. They have also discovered more than 1,000 artifacts—bullets, barbed wire, rusting tin cans of Australian bully beef (corned beef), bayonets, human bones—that provide a compelling picture of life and death in one of history’s bloodiest battlegrounds. And some finds would also seem to call into question the Turkish government’s recent push to recast the battle as a triumph for the Ottoman Empire and Islam.

***

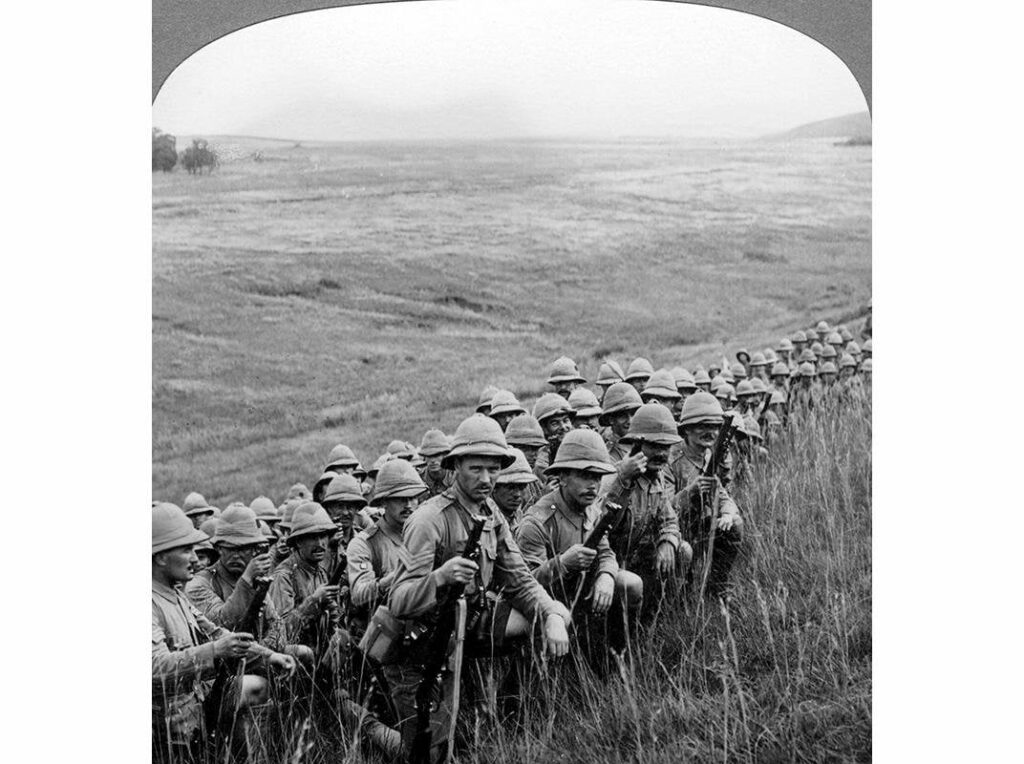

On a warm September morning, I join McGibbon and Simon Harrington, a retired Australian rear admiral and member of the field team, on a tour of Holly Ridge, the hillside where Australian troops faced Ottoman Army regiments for four months in 1915. Thickets of pine, holly and wattle gouge my legs as I follow a precipitous trail above the Aegean Sea. “The Australians climbed up from Anzac Cove on April 25,” says McGibbon, gesturing toward the coastline a couple of hundred feet below us. “But the Turks headed them off, and both sides dug in.”

The two historians spent much of September 2013 delineating this former front line, which ran roughly along both sides of a modern-day fire road. McGibbon, clad like his colleague in a bush hat and safari gear, points to depressions half hidden in the brush on the roadside, which he and Harrington tagged last year with orange ribbons. The trenches have eroded away, but the historians look for telltale clues—such as the heavy vegetation that tends to grow here because of rainfall accumulation in the depressions.

McGibbon points out a crater just off the road, which he identifies as a “slump,” a depression above an underground corridor. Ottomans and Allies burrowed tunnels beneath their foes’ trenches and packed them with explosives, often causing enormous casualties; each side also constructed defensive tunnels to intercept enemy diggers. “Battles sometimes erupted underground” where the two digging teams confronted each other, McGibbon says.

He picks up a fist-size chunk of shrapnel, one of countless fragments of materiel that still litter the battlefield. Most important relics were carted off long ago by second-hand dealers, relatives of veterans and private museum curators such as Ozay Gundogan, the great-grandson of a soldier who fought at Gallipoli and founder of a war museum in the village of Buyuk Anafarta. His museum displays British badges, canvas satchels, wheelbarrows, French sun helmets, belt buckles, map cases, bugles, Turkish officers’ pistols, rusted bayonets and round bombs with fuses, which were hurled by Ottoman troops into enemy trenches.

But Harrington says his team’s modest relics shed light on what happened here. “What we have found has remained in its context,” he says. For example, in the Australian trenches, the historians uncovered piles of tin cans containing bully beef—testifying to the monotony of the Anzac diet. The Ottomans, by contrast, received deliveries of meat and vegetables from nearby villages and cooked in brick ovens inside the trenches. The team has recovered several bricks from these ovens.

As trench warfare bogged down, the architecture of the trenches became more elaborate. The Anzac forces brought in engineers who had learned their trade in the gold mines of western Australia: They constructed zigzagging frontline corridors with steps leading up to firing recesses—some of which can still be seen today. A maze of communications and supply trenches ran up to the front line, becoming so complex, says Harrington, that “men couldn’t find their way back to the front lines, and had to be rescued.”

In lower sections of the battlefield, the enemies faced each other from 200 or 300 yards away, but on the narrow ridges near Chunuk Bair, one of the highest points on the peninsula and a principal objective of the Allies, Anzac and Ottoman soldiers were separated by just a few yards—close enough for each side to lob grenades and bombs into each other’s trenches. “You dug deep, and you erected barbed-wire netting on top to protect yourself,” says Harrington. “If you had time, you threw the grenades back.”

Most of the fighting took place from deep inside these bunkers, but soldiers sometimes emerged in waves—only to be cut down by fixed machine guns. The Allies had insufficient medical personnel in the field and few hospital ships, and thousands of injured were left for days in the sun, pleading for water until they perished.

The Turkish soldiers fought with a tenacity that the British—ingrained with colonial attitudes of racial superiority—had never anticipated. “The soldiers from the Anatolian villages were fatalists raised on hardship,” the historian L.A. Carlyon wrote in his acclaimed 2001 study Gallipoli. “They knew how to hang on, to endure, to swallow bad food and go barefoot, to baffle and frustrate the enemy with their serenity in the face of pain and death.”

The corpses piled up in the trenches and ravines, often remaining uncollected for weeks. “Everywhere one looked lay dead, swollen, black, hideous, and over all a nauseating stench that nearly made one vomit,” observed Lt. Col. Percival Fenwick, a medical officer from New Zealand, who participated in a joint burial with Turkish forces during a rare ceasefire that spring. “We exchanged cigarettes with the [Turkish] officers frequently…there was a swathe of men who had fallen face down as if on parade.”

By August 1915, after a three-month stalemate, the Allied commanders at Gallipoli were desperate to turn the tide. On the evening of August 6, British, Australian and New Zealand troops launched a major offensive. The attack started on a plateau called Lone Pine, where Australians launched a charge at Turkish positions 100 yards away. They captured their objective but suffered more than 2,000 casualties. Australian engineer Sgt. Cyril Lawrence came upon a group of Australian injured, huddled inside a tunnel that they had just captured from the Turks. “Some of their wounds are awful yet they sit there not saying a word, certainly not complaining, and some have actually fallen off to sleep despite their pain,” he wrote. “One has been shot clean through the chest and his singlet and tunic are just saturated with blood, another has his nose and upper lip shot clean away….Lying beside them was a man asleep. He had been wounded somewhere in the head, and as he breathed the blood just bubbled and frothed at his nose and mouth. At ordinary times these sights would have turned one sick but now they have not the slightest effect.”

Three regiments from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade meanwhile advanced from north of Anzac Cove up a trail just to the west of a rugged outcropping called Table Top. Columns of Australian, British and Nepalese Gurkha troops followed them—taking different routes toward the 889-foot summit of Chunuk Bair. They moved through a confusing terrain of outcroppings, gorges and razorback ridges overgrown with brush. Their nicknames—Baby 700, Shrapnel Valley, the Sphinx, Russell’s Top, Razor’s Edge, the Nek—suggested the intimacy with which the soldiers had come to regard them. “There was a feeling of panic and doubt in the air as to where we were and where we were going,” recalled Maj. Cecil Allanson, commander of a 6th Gurkhas battalion.

The Ottoman troops had just a single artillery platoon, 20 men, dug in atop the mountain, hardly enough to withstand an invading force of 20,000. But in difficult and unfamiliar territory, and enveloped by darkness, the Allied soldiers struggled to find their way. One New Zealand regiment wandered up a ravine to a dead end, reversed course and ended up back where it started hours later. The assault got nowhere.

The Nek, a small plateau just below Chunuk Bair, came to epitomize the folly—and would later be immortalized in the powerful final scene of Peter Weir’s Gallipoli. At 4:30 a.m. on August 7, 1915, under dim moonlight, the 3rd Australian Light Horse Brigade, composed mainly of farm and ranch boys from the outback, sat in their trenches on this small patch of ground, waiting to attack. Allied howitzers at Anzac Cove unleashed a furious bombardment. But the barrage ended seven minutes ahead of schedule, a fatal lapse that allowed the Turks to retake their positions before the Australian infantry charge. When the first wave went over the top, the Turks opened fire with machine guns, and killed nearly every attacker in 30 seconds. “I was in the first line to advance and we did not get ten yards,” recalled Sgt. Cliff Pinnock. “Everyone fell like lumps of meat….All your pals that had been with you for months and months blown and shot out of all recognition. I got mine shortly after I got over the bank, and it felt like a million ton hammer falling on my shoulder. I was really awfully lucky as the bullet went in just below the shoulder blade round by my throat and came out just a tiny way from my spine very low down on the back.”

The second wave went over minutes later and again, almost all were killed. A third wave was shot to the ground, and a fourth. Later that morning, Maj. Gen. Alexander John Godley, loathed by his troops, ordered the New Zealanders to follow; they too sustained massive casualties.

The next night, 760 men from New Zealand’s Wellington Battalion made a dash up Chunuk Bair. The site was held for two days and nights, only to be retaken when the Turks counterattacked. The Australians and New Zealanders suffered 10,000 casualties in four days. Said Pinnock: “It was simply murder.”

At the same time as the offensive, the British launched a major amphibious landing at Suvla Bay, a few miles north of Anzac Cove. But they never made a serious attempt to break out of that beachhead. In December, with blizzards and frigid temperatures sapping morale, and Ottoman forces moving artillery into position to begin bombarding the trenches, Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, ordered a nighttime withdrawal of the remaining 80,000 troops from Gallipoli. Using self-firing guns and other diversions, the Allied forces managed to board ships and sail away from the peninsula with almost no casualties. It was one of the few logistical successes in the eight-month debacle.

***

A hundred years later, historians, politicians and others continue to debate the larger meaning of the Gallipoli battle. For the Allies, it came to symbolize senseless loss, and would have a devastating effect on the careers of the men who conceived it. Doubts had already been raised within the British government about Winston Churchill, following a failed attempt by British naval troops to relieve besieged Belgian soldiers at Antwerp in October 1914. “Winston is becoming a great danger,” declared Prime Minister Lloyd George. “Winston is like a torpedo. The first you hear of his doings is when you hear the swish of the torpedo dashing through the water.”

Although Churchill bore only part of the blame for the Gallipoli debacle, George and other British leaders now challenged his judgment in matters of military operations and strategy, and he was forced to resign his post. He served in minor cabinet positions, and lost his seat in the House of Commons, finally winning back a seat in 1924. That same year, he became Chancellor of the Exchequer and his political redemption began.

Lord Kitchener saw his own reputation for military brilliance shattered. (He would drown a year later when his battleship sank after striking a mine, saving him from the disgrace of a full parliamentary inquiry.)

The military historian Peter Hart faults the British leadership for “a lack of realistic goals, no coherent plan, the use of inexperienced troops…negligible artillery support, totally inadequate logistical and medical arrangements [and] a gross underestimation of the enemy.” Gallipoli, he concludes, “was damned before it started.” Carlyon excoriates Kitchener for his failure to provide troops and weaponry in a timely manner, and sharply criticizes Gen. Sir Ian Hamilton, commander of the campaign, who acquiesced to Kitchener’s indecisiveness and rarely stuck up for his men.

By contrast the German general who commanded the Turks, Otto Liman von Sanders, brilliantly deployed the Ottoman 5th Army, 84,000 well-equipped soldiers in six divisions. And the Turkish division commander Mustafa Kemal, who saw the dangers posed by the Australian and New Zealand landings at Anzac Cove, moved his troops into position and held the ridgeline for five months. Unlike the Allied generals, who commanded troops from the safety of the beach or from ships anchored in the Aegean, Kemal often stood with his men on the front lines, lifting their morale. “There were complaints to Istanbul about him, that he was always risking his life. And in fact he was hit by shrapnel,” says Sabahattin Sakman, a former Turkish military officer and a columnist for a popular secular newspaper in Istanbul.

The view that the battle’s outcome was decided by military leadership was codified by none other than U.S. Army Lt. Col. George Patton, who concluded in a 1936 report, “Had the two sets of commanders changed sides, the landing would have been as great a success as it was a dismal failure.”

The Ottoman victory at Gallipoli, however, proved to be the empire’s last gasp. Known as “the sick man of Europe,” it suffered punishing defeats in the Middle East at the hands of British and Arab forces, and collapsed in 1918. Its territories were parceled out to the victorious Allies. In November of that year, British and French warships sailed unopposed through the Dardanelles and occupied Constantinople.

Kemal (who would later take the name Ataturk) went on to lead the Turkish National Movement in a war against Greece, winning back territory the Ottomans had forfeited. In 1923 Kemal would preside over the creation of the secular nation of Turkey. For that reason, secular Turks have long viewed the battle of Canakkale as marking the birth of their modern society.

In recent years, though, the Turkish government has minimized Ataturk’s role in the battle—part of an orchestrated campaign to rewrite history. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), a socially conservative movement with deep Islamic roots, has spun the battle as a victory for Islam. Yet Erdogan, however conservative, presides over the nation Ataturk founded, a country regarded by many as a bulwark against the ultimate jihadist threat—ISIS—as Turkey cooperates with the West to counter the insurgents.

The government buses hundreds of thousands of Turks to the battlefield to present its version of Ottoman-era glory. “They are selling this as a religious victory now,” Kenan Celik tells me as we walk around the Turkish War Memorial, a monolithic archway surrounded by Turkish flags, overlooking Cape Helles at the southern end of the peninsula. “They’re telling people, ‘We won this by the hand of God,’ rather than with German help,” Celik says.

At the annual Canakkale Victory Day commemoration last March, “10,000 people were praying at the memorial, something you never saw a decade ago,” says Heath Lowry, a retired professor of Turkish history at Princeton University, who lives in Istanbul. In 2012 the government opened a multimillion-dollar entertainment and education center near Anzac Cove. Visitors walk through trenches, experience simulated shellfire through 3-D glasses—and watch a propaganda film linking Erdogan’s government to the Islamic fighters who achieved victory here. “We are here to express gratitude for the sacrifice made for us,” Rahime, a 30-year-old woman from Istanbul, told me after leaving the center. She came on a free trip organized by Erdogan’s party, which is facing an election in June. “This was a victory for Islam,” she says.

But the ongoing fieldwork by the joint Turkish-Anzac team doesn’t always bolster the official narrative. A few years ago, in the Ottoman trenches, the archaeologists discovered bottles of Bomonti beer, a popular wartime brand brewed in Constantinople. News of the find was published in Australian newspapers; the Turkish government reacted with dismay and denial. “They said, ‘Our soldiers didn’t drink beer. They drank tea,’” says Tony Sagona, a professor of archaeology at the University of Melbourne who leads the Australia-New Zealand team at Gallipoli. Turkish officials insisted that the bottles belonged to German officers who often fought alongside Turkish conscripts and put subtle pressure on the team leaders to back up that version of events. “I told them that the evidence is inconclusive,” says Mithat Atabay, leader of the project and a history professor at March 18 University in Canakkale, across the Dardanelles from Gallipoli. Drinking alcohol was a normal activity in the Ottoman Empire, he points out, “a way for young men to find their freedom.” It perhaps offered a small bit of comfort for men marooned in one of history’s bloodiest battlefields.

Joshua Hammer | READ MORE

Joshua Hammer is a contributing writer to Smithsonian magazine and the author of several books, including The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu: And Their Race to Save the World’s Most Precious Manuscripts and The Falcon Thief: A True Tale of Adventure, Treachery, and the Hunt for the Perfect Bird.