Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is like a mousetrap salesman; the moment he plugs one hole, the mouse peeks out of the other.

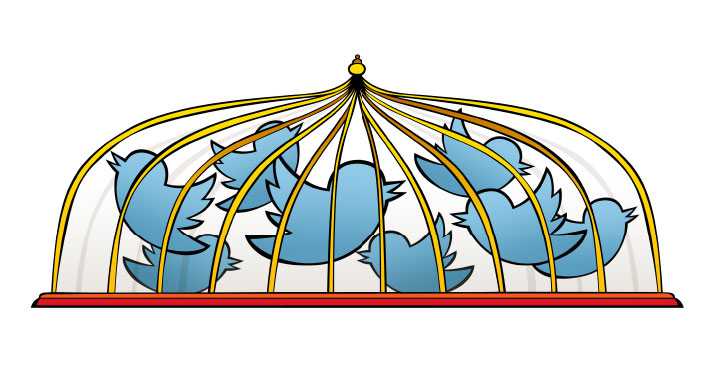

His latest move to block dissent in Turkey is to ban Twitter, but millions of Turkish tweeters have, with characteristic ingenuity, found ways to circumvent this ban.

On the 200th anniversary of Darwin’s birth in 2009, a former Turkish judge at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), Rıza Türmen, noted about the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government, “What they are attempting to achieve today [after coming to power in 2002] is social engineering, a radical transformation of society.”

This includes a reform of the education system, which makes it possible for pupils to attend religious schools (imam-hatip schools) after only four years of primary education, the easing of restrictions on Quran courses and an abolition of the coefficient system to enable students from imam-hatip schools to enter universities on equal terms with graduates from other high schools.

This is in keeping with Prime Minister Erdoğan’s declared goal to raise a “religious generation,” and also involves other forms of social engineering such as a ban on the sale of alcohol in municipal and public restaurants in most of Turkey’s provinces. This culminated last May with a new law that imposes severe restrictions on the consumption and sale of alcohol.

Although both the preamble and Article 24 of the Turkish Constitution stipulate that no one shall be allowed to exploit or abuse religion or religious feelings for the purpose of personal or political influence, this is precisely what Prime Minister Erdoğan and his AKP government have done. Or as the Turkish imam, Fethullah Gülen, now Erdoğan’s arch-enemy, put it in the Financial Times, “The reductionist view of seeking political power in the name of a religion contradicts the spirit of Islam.”

Gezi Park

Four days after the alcohol legislation was passed, a boiling point was reached and the occupation of GeziPark in İstanbul began. What started as an environmental protest developed into nationwide protests against Erdoğan’s tyranny, which now proves to have far-reaching consequences for Turkey. As Alev Yaman, author of the English PEN’s report on the GeziPark protests, concludes, “A culture of protest and dissent has been established among a previously politically disenfranchised younger generation.”

Social media played a significant role during the Arab Spring, and in Egypt it contributed to the downfall of President Hosni Mubarak. After the demonstrations in Tahrir Square, Erdoğan advised Mubarak: “Listen to the shouting of the people, the extremely humane demands. Without hesitation, satisfy the people’s desire for change.” However, during the GeziPark uprising, he failed to take his own advice but instead supported the police crackdown on demonstrators.

Research by Eira Martens from DW Akademie on the role of social media during the revolt in Egypt showed that Twitter and Facebook mobilized protesters and helped develop a collective identity, or more precisely, a form of solidarity. Consequently, images of police brutality, also on YouTube and Flickr, made people not only angrier but also lowered their threshold of fear.

The same applied to the GeziPark protests, but whereas in Egypt the most popular hashtag was used in less than one million tweets, an analysis by New YorkUniversity estimates that out of more than 22 million tweets related to the protests in Turkey, the two main hashtags were mentioned about 6 million times. In Turkey’s case, around 90 percent of all the tweets came from within Turkey, whereas in Egypt only 30 percent were from inside the country.

In Turkey, it is estimated that the AKP government has the final word over 90 percent of the media, that is, newspapers and television. This was evidenced in an interview on CNN Türk with Fatih Altaylı, the editor-in-chief of the Turkish daily Habertürk, who complained that instructions were “pouring down” every day from somewhere.

Leaked wiretaps, one of which Erdoğan has confirmed is genuine, reveal constant pressure from the prime minister’s office and Erdoğan himself on media owners and executives. In one recording, Erdoğan’s son, Bilal, allegedly informs his father that the next day’s headlines have been agreed upon with the pro-government media.

Consequently, Turkish media coverage of the GeziPark protests was nothing short of scandalous; CNN Türk broadcast a documentary on penguins and seven pro-government newspapers ran identical headlines with the same quote from the prime minister. Four television channels that covered the events were fined for “harming the physical, moral and mental development of children and young people” and 845 journalists lost their jobs

In its report on the role of social media in the Turkish protests, New YorkUniversity said that part of the reason for the extraordinary number of tweets was a response to the lack of media coverage; furthermore, it said that Turkish protesters are replacing traditional reporting with crowd-sourced accounts expressed through social media such as Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr. The report concludes that this is an impressive utilization of social media in overcoming the barriers created by semi-authoritarian regimes.

There is also the fact that, according to another study, Turkey has the top Twitter penetration rate, with 31 percent of an Internet population of 36.5 million being Twitter users.

No wonder Prime Minister Erdoğan calls Twitter “a menace” and finds social media to be “the worst menace to society.”

Dec. 17

The anti-corruption operation that went public in İstanbul on Dec. 17, and the subsequent scandal, constitutes a major challenge to Prime Minister Erdoğan’s government. The response has been a massive cover-up, with the removal of thousands of police officers and hundreds of prosecutors and judges who could continue the investigation and therefore threaten the government’s legitimacy.

The AKP has made use of its parliamentary majority to block the reading of indictments that involve four former government ministers, and it has also blocked the formation of an investigative commission. As Fethullah Gülen noted in the Financial Times, “A small group within the government’s executive branch is holding to ransom the entire country’s progress.” And one of the founders of the AKP, Abdüllatif Şener, has even said that Erdoğan is prepared to drag Turkey into a civil war to retain his hold on power.

The immediate threat to the AKP government is the outcome of the local elections on Sunday, which will act as a barometer for the party’s popularity. Some 35 percent are reckoned to be the AKP’s core voters and, according to a Sonar survey, 80 percent of them don’t use the Internet. Added to this is the fact that Turkey has a relatively low newspaper circulation (96 papers bought daily per 1,000 people), which increases the importance the government attaches to the control of both public and private TV networks.

Nevertheless, since February, almost daily tweets from Haramzadeler (Sons of Thieves), joined by Başçalan (Prime Thief) and Hırsıza Oy Yok (No Votes for Thieves), have contained links to wiretaps on YouTube and other social media allegedly involving Prime Minister Erdoğan, his family and ministers in bribery, tender rigging, media manipulation and interference with the judiciary

Despite widespread international criticism, President Abdullah Gül, “Mr. Nice Guy,” has approved new legislation giving the government control over the Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK) and the powers to block important websites. Prime Minister Erdoğan has now (ab)used these powers by imposing a blanket ban on Twitter through the Telecommunications Directorate (TİB), which has also blocked access to Google’s domain name server (DNS). Furthermore, Erdoğan has threatened to block access to YouTube and Facebook.

In the first few hours of the ban, there was a massive increase in the number of tweets sent in Turkey, and Turkish users have found ways to circumvent the ban by using virtual private networks (VPN) or Tor. Nevertheless, there has since been a marked decrease in the number of Turkish tweets. Following several complaints, a Turkish administrative court has also ordered a stay of execution, which Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç said the government will implement

Erdoğan has, in turn, elevated the conflict to a “new war of independence,” with a TV commercial showing Turks from all walks of life rallying round the flag. However, as Turkish economist Emre Deliveli remarked on his blog, “There are several million people in Turkey who would believe the world was flat if Gazbogan [Erdoğan] told them so.”

Robert Ellis is a regular commentator on Turkish affairs in the Danish and international press.