THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

October 20, 1923

THERE was a time when Angora was famous solely,

for cats and goats. Today the shambling, timeworn

town far up in the Anatolian hills has

another, and world-wide significance. It is not

only the capital of the reconstructed Turkish

Government and the seat therefore of the most

picturesque of all contemporary experiments

in democracy, but is likewise the home of

Ghazi Mustapha Kemal Pasha—to give him

his full title—who is distinct among the few

vital personalities revealed by the bitter

backwash of the World War.

Only Lenine and Mussolini vie with him

for the center of that narrowing stage of compelling

leadership. Each of these three remarkable

men has achieved a definite result

in a manner all his own. Lenine imposed an

autocracy through force and blood. Mussolini

created a personal and political dictatorship

in which he dramatized himself. Kemal

not only led a beaten nation to victory and

dictated terms to the one-time conqueror, but

set up a new and unique system of administration.

Lenine and Mussolini have almost been

done to death by human or, in the case of the

soviet overlord, inhuman interest historians.

Kemal Pasha is still invested with an element

of mystery and aloofness largely begot of the

physical inaccessibility of his position. To

the average American he is merely a Turkish

name vaguely associated with some kind of

military achievement. The British Dardanelles

Expedition know it much better, for he

frustrated the fruits of that immense heroism

written in blood and agony on the shores of

Gallipoli. The Greeks have an even costlier

knowledge, because he was the organizer of

the victory that literally drove them into the

sea in one of the most complete debacles of

modern times.

At Angora I talked with this man in a

critical hour of the war-born Turkish Government.

The Lausanne Conference was at the

breaking point. War or peace still hung in the

balance. Only the day before, Rauf Bey, the

Prime Minister, had said to me: “If they [the Allies]

want war they can have it.” The air was charged with

tension and uncertainty. Over the troubled scene brooded

the unrelenting presence of the chieftain I had traveled

so far to see. Events, like the government itself, revolved

about him.

In difficulty of approach and in the grim and dramatic

quality of the setting, Anatolia was strongly reminiscent

of my journey a year ago to the Southern Chinese front to

see Sun Yat-sen. Between him and Kemal exists a certain

similarity. Each is a sort of inspired leader. Each has his

kindling ideal of a self-determination that is the by-product

of fallen empire. Here the parallel ends. Kemal is the

man of blood and iron—an orientalized Bismarck, as it

were—dogged, ruthless, invincible; while Sun Yat-sen

is the dreamer and visionary, eternal pawn of chance, and

with as many political existences—and I might add, governments-

-as the proverbial cat has lives.

Turkey for the Turks

AS WITH men, so with the peoples behind them. You

have another striking contrast. While China flounders

in well-nigh incredible political chaos, due to incessant

conflict of selfish purpose and lack of leadership, Turkey

has emerged as a homogeneous nation for the first time in

its long and bloody history, with defined frontiers, a real

homeland, and a nationalistic aim that may shape the

destiny of the Mohammedan world, and incidentally affect

American commercial aspirations in the Near East.

“Turkey for the Turks” is the new slogan. The instrument

and inspiration of the whole astonishing evolution—it is

little less than a miracle when you realize that in 1919

Turkey was as prostrate as defeat and bankruptcy could

bring her—has been Kemal Pasha.

He was the real objective of my trip to Turkey. Constantinople

with its gleaming mosques and minarets, and

still a queen among cities despite its dingy magnificence,

had its lure, but from the hour of my arrival on the shores

of the Golden Horn my interest was centered on Angora.

I had chosen a difficult time for the realization of this

ambition. The Lausanne Conference was apparently

mired, and the long-awaited peace seemed more distant

than ever. A state of war still existed. The army of occupation

gave the streets martial tone and color, while a vast

Allied fleet rode at anchor in the Bosporus or boomed at

Kemal Pasha as Field Marshal of the Turkish

Army. The Autograph Reads: “Ghazi Musta•

pha Kemal Pasha, Angora, July tith”

target practice in the Sea of Marmora. The capital in the

Anatolian hills had become even more inaccessible.

Every barrier based on suspicion, aloofness and general

resentment of the foreigner—the usual Turkish trilogy—

all tied up with endless red tape, worked overtime. It was

a combination disastrous to swift American action. My

subsequent experiences emphasized the truth of the wellknown

Kipling story which dealt with the fate of an energetic

Yankee in the Orient whose epitaph read: “Here

lies a fool who tried to hustle the East.”

To add to all this handicap begot of temperament and

otherwise, the Turks had begun to realize, not without

irritation, that the consummation of the Chester Concession

was not so easy as it looked on paper. The last civilian

who successfully applied for permission to go to Angora

had been compelled to linger at Constantinople seven

weeks before he got his vessica—as a visa is called in Turkish.

Two or three others had departed for home in disgust

after four weeks of watchful and fruitless waiting. The

prospect was not promising.

When I paid my respects to Rear Admiral Mark L.

Bristol, the American High Commissioner, on my first

day in Constantinople, I invoked his aid in getting to

Angora. He promptly gave me a letter of introduction

to Dr. Adnan Bey, then the principal representative of

Angora in Constantinople, through whom all permits had

to pass.

I went to see him at the famous Sublime Porte, the

Foreign Office and the scene of so much sinister Turkish

history. Here the sordid tools of Abdul-Hamid, the Red

Sultan, and others no less unscrupulous, lived their day.

I expected to find the structure almost as imposing as its

richer mate in history, the Mosque of St. Sophia. It

proved to be a dirty, rambling, yellow building without

the slightest semblance of architectural beauty, and

strongly in need of disinfecting.

In Adnan Bey I found my first Turkish ally.Moreover,

I discovered him to be a man of the world with a broad

and generous outlook. An early aid of Kemal in the

precarious days of the nationalist movement, he became

the first vice president of the Angora Government.

Moreover, he had another claim to fame, for he is

the husband of the renowned Halide Hanum, the

foremost woman reformer of Turkey, whom I

was later to meet in interesting circumstances

at Munich, and whose story will be

disclosed in a subsequent article. Adnan

Bey, however, is not what we would call a

professional husband in America. Long before

he rallied to the Kemalist cause he was

widely known as one of the ablest physicians

in Turkey.

He at once sent a telegram to Angora asking

for my permission to go. This permission

is concretely embodied in a pass—the aforesaid

vessica—which is issued by the Constantinople

prefect of police. Back in the days of

the Great War it was a difficult procedure to

get the so-called white pass which enabled

the holder to go to the front. Compared with

the coveted permission to visit Angora, that

pass was about as inaccessible as a public

handbill, as I was now to discover.

Adnan Bey told me that he would have an

answer from Angora in about three days. I

found that three days was like the Russian

word seichas which technically means “immediately”

but when employed in action or

rather lack of action on its own ground, usually

spells “next month.”

Red ,Tape Entanglements

AFTER a week passed the American Embassy

inquired of the Sublime Porte if they

had heard about my application, but no word

had come. A few days later Turkish officialdom

went mad. An order was promulgated

that no alien except of British, French or

Italian nationality could enter or leave Constantinople

without the consent of Angora.

People who had left Paris or London, and they

included various Americans, with existing credentials,

were held up at the Turkish frontier,

despite the fact that the order had been issued

after they had started. Thanks to Admiral Bristol’s

prompt and persistent endeavors, the frontier ban was

lifted from Americans. Angora became swamped overnight

with telegraphic protests and requests, and I felt that

mine was completely lost in the new and growing shuffle.

Meanwhile I had acquired a fine upstanding young Turk,

Reschad Bey by name, who spoke English, French and

German fluently, as dragoman, which means courier and

interpreter. No alien can go to Angora without such an

aid, because, save in a few isolated spots, the only language

spoken in Anatolia is Turkish. Reschad Bey was really an

inheritance from Robert Imbrie, who had just retired

after a year as American consul at Angora. Reschad Bey

had been his interpreter. Much contact with Imbrie had

acquainted him with American ways and he thoroughly

sympathized with my impatience over the delay. He had

a strong pull at Angora himself and sent some telegrams

to friends in my behalf.

At the expiration of the second week Admiral Bristol

made a personal appeal to Adnan Bey to expedite my permission,

and a second strong telegram went from the Sublime

Porte to Angora. Other Turkish and American individuals

whom I had met added their requests by wire. Of

course I was occupied with other work, but I had only a

limited amount of time at my disposal and when all was

said and done, Kemal was the principal prize of the trip

and I was determined to land him. Early in July therefore

I sent Reschad Bey to Angora to find out just what

the situation was. He departed on the morning of the

Fourth. When I returned to my hotel from attending the

Independence Day celebration at the embassy I found a

telegram from Angora addressed to Reschad Bey in my

care from one of his friends in the government, saying that

my permission to go to Angora had been wired nine days

before! Yet on the previous morning the Sublime Porte

had declared that Angora was still silent on my request.

Upon investigation I found that in the tangle of red

tape at the prefecture of police the coveted telegram had

been shoved under a pile of papers and no one knew anything

about it until a long search, instigated at my request,

had disclosed the anxiously awaited message. It was a

typically Turkish procedure, and just the kind of thing

that might have happened at an official bureau anywhere

in China. Before Reschad Bey reported to me after his

return I had the ressica in my possession and was getting

ready to start.

THE SATURDAY EVENING POST 9

Difficult as was this first step, it was matched in

various handicaps by nearly every stage of the actual

journey. Again I was to run afoul of Turkish official

decree.

In ordinary circumstances, if I had been a Turk I

could have boarded a train at Haidar Pasha, which is

just across the Bosporus by ferry from Constantinople

and the beginning of the Anatolian section of the

much-discussed Berlin-to-Bagdad Railway, and gone

without change to Angora in approximately twentyseven

hours. It happened, however, that the whole

Turkish Army of considerably more than 250,000 men

was mobilized beyond Ismid and along the railroad

right of way. No alien was permitted to make this

journey. Instead of the comparatively easy trip by

rail—I say ” comparatively ” advisedly—he was compelled

to go by boat to Mudania, then by rail to Brusa,

and subsequently by motor all day across the Anatolian

plain to Kara Keuy, where he would pick up the

train from Haidar Pasha. Instead of twenty-seven

hours, this trip—and it was the one I had to make—

took exactly fifty-five hours.

Going to Angora these days is like making an expedition

to the heart of China or Africa. In the first

place you must carry your own food. There are other

preliminaries. One of the most essential, even if it is

not the most esthetic, is to secure half a dozen tins

of insect powder. The moment you leave Constantinople—

and for that matter even while you are within

the storied precincts of the great city—you make the

acquaintance of endless little visitors of every conceivable

kind and bite. Apparently the average Turk

has become more or less inured to the inroads of vermin,

but even long experience with trench warfare

does not cure the European of aversion to it.

It was on a brilliant sunlight Monday morning that

I left Constantinople for Angora. Admiral Bristol

had placed a submarine chaser in command of Captain

T. H. Robbins at my disposal and we were therefore

able to dispense with the crowded and none too clean

Turkish boat. Accompanied by Lewis Heck, who had

been the first American High Commissioner to Turkey

after the Armistice, and who now had a business mission

at Angora, and the faithful Reschad Bey, I made the

journey to Mudania across the Sea of Marmora in

four hours, arriving at noon. Until November, 1922,

Mudania was merely a spot on the Turkish map. After

the Greek debacle, and when the British and Turkish

armies had come within a few feet of actual collision at

Chanak, and war between the two powers seemed inevitable,

General Sir Charles Harington, commander of the

British forces in Turkey, and Ismet Pasha—the same Ismet

who led the Allied delegates such a merry diplomatic chase

at Lausanne—met here and arranged the famous truce

that was the prelude to the first Lausanne Conference.

Madame Brotte and Her Hotel

OVE RNIG HT the village became famous. The small stone

house near the quay where the conference was held is now

occupied by a Turkish family and is overrun with children.

Instead of making the forty-mile journey to Brusa in the

toy train that runs twice a day, we traveled in a brand-new

Kemal With His Puppies

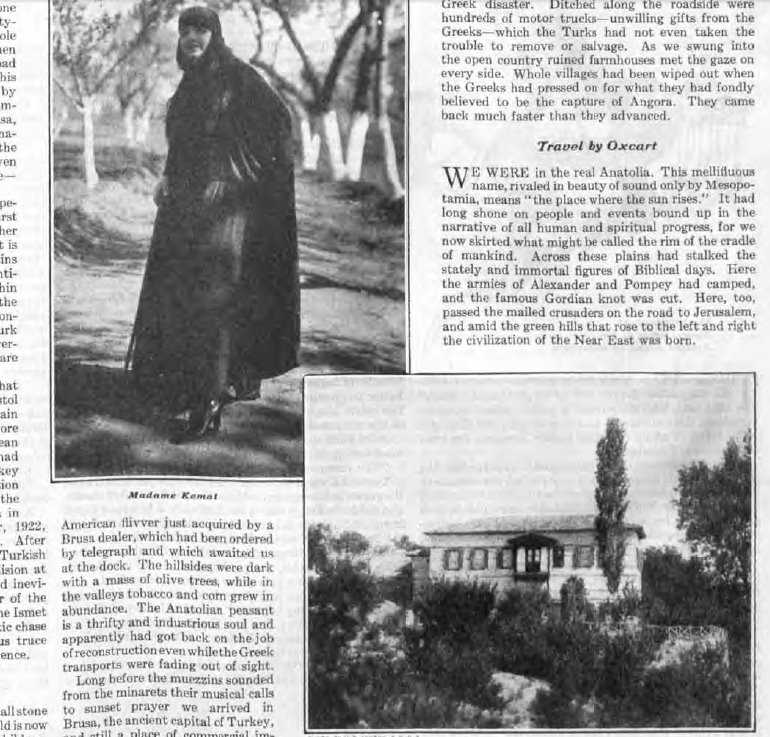

Madame Kama!

American flivver just acquired by a

Brusa dealer, which had been ordered

by telegraph and which awaited us

at the dock. The hillsides were dark

with a mass of olive trees, while in

the valleys tobacco and corn grew in

abundance. The Anatolian peasant

is a thrifty and industrious soul and

apparently had got back on the job

of reconstruction even while the Greek

transports were fading out of sight.

Long before the muezzins sounded

from the minarets their musical calls

to sunset prayer we arrived in

Brusa, the ancient capital of Turkey,

and still a place of commercial importance.

Here we stopped the night

at the Hotel d’Anatolie, where I bade

farewell to anything like comfort and convenience until

my return there on my way back to Constantinople.

This hotel is one of the famous institutions of Anatolia.

It is owned by Madame Brotte, who is no less

distinguished than her hostelry. Out in her pleasant

garden, where we could listen to the musical flow of a

tiny cataract, this quaint old lady, still wearing the

white cap of the French peasant, told me her story.

She had been born in Lyons, in France, eighty-four

years ago, and came to Anatolia with her father, a silk

expert, when she was twenty-one. Brusa is the center

of the Turkish silk industry, which was founded and is

still largely operated by the French. Madame had

married the proprietor of the hotel shortly after her

advent, and on his death took over the operation.

Wars, retreats and devastations beat about her, but

she maintained her serene way. She had lived in Turkey

so long that she mixed Turkish words with her

French. Listening to her patter in that fragrant environment,

and with the memory of the excellent French

dinner she had

served, made it difficult for me to realize

that I was in Anatolia and not in France.

Anatolia, let me add, is bone-dry so far as alcohol is

concerned. The one regret that madame expressed was

that the Turks sealed up her wine cellar, and only heaven

and Angora knew when those seals would be lifted. It

is worth mentioning that during the eight days I spent

in Anatolia I never saw a drop of liquor. It is about

the only place in the world where prohibition seems to

prohibit. Constantinople is a different, and later, story.

In Madame Brotte I got another evidence of a curious

formula of colonial expansion. When you knock

about the world, and especially the outlying places,

you discover that certain races follow definite rules when

they are implanted in foreign soil. The first thing that

The Kemal Home at Angora

I now had my first contact with what has been well

called the Anatolian qxcart symphony. It is the weirdest

perhaps of all sounds, and is emitted from the ungreased

wood-wheeled carts drawn by oxen or water buffalo, which

provide the only available vehicle for the Turkish farmer.

There has been no change in its noise or construction since

the days of Saul of Tarsus. It is a violation of etiquette

for the driver of one of these carts—the roads are alive with

them—to be awake in transit, incredible as this seems when

you have heard the frightful noise. He awakes only when

the screech stops. Silence is his alarm clock. These carts

do about fifteen miles a day. When the Greeks had the

important Southern Turkish ports bottled up, all of Kemal’s

supplies were hauled in these carts for over two hundred

miles to Angora.

The farther we traveled the more did the country take

on the aspect of Northern France after the war. Hollyhocks

were growing in the shell holes, and there were always

the gaunt, stark ruins of a house or village sentineling the

landscape. We passed through the village of In Onu, where

the Greeks and the Turks had met in bloody battle, and

just as the sun was setting we drew up at Kara Keuy,

which is merely a railway station flanked by a few of the

coffeehouses that you find everywhere in Turkey. A contingent

of Turkish troops was encamped near by. Before

we could get coffee we had to submit our papers for examination

by the police.

An hour later the train that had left Haidar Pasha that

morning pulled in. We bagged a first-class compartment

and started on the final lap to Angora. Midnight found

us at Eski-Shehr, once a considerable town, where the

Greeks and the Turks were at death grips for months.

After the Turkish retirement in 1921 the town was burnt

by the Greeks. No sooner was I on the train and trying

(Continued on Page 14I)

the English do is to start a bank. The Spanish invariably

build a church, while the French set up a café.

So it was in Anatolia.

It was with a certain regret that I bade farewell the

next morning to the dear old French dame. In the

same flivver that brought us up from Mudania we

started on the all-day run to Kara Keuy. At the outskirts

of Brusa I saw the first tangible signs of the

Greek disaster. Ditched along the roadside were

hundreds of motor trucks—unwilling gifts from the

Greeks—which the Turks had not even taken the

trouble to remove or salvage. As we swung into

the open country ruined farmhouses met the gaze on

every side. Whole villages had been wiped out when

the Greeks had pressed on for what they had fondly

believed to be the capture of Angora. They came

back much faster than they advanced.

Travel by Oxcart

WE WERE in the real Anatolia. This mellifluous

name, rivaled in beauty of sound only by Mesopotamia,

means “the place where the sun rises.” It had

long shone on people and events bound up in the

narrative of all human and spiritual progress, for we

now skirted what might be called the rim of the cradle

of mankind. Across these plains had stalked the

stately and immortal figures of Biblical days. Here

the armies of Alexander and Pompey had camped,

and the famous Gordian knot was cut. Here, too,

passed the mailed crusaders on the road to Jerusalem,

and amid the green hills that rose to the left and right

the civilization of the Near East was born.

fflflfWVItrolfolrftf

144iltalf 4J..44.4,1.44.4.4

ritpg !

Aola

-“,*

THE SfITURDAY EVENING POST 141

TEZETEL PZOIEZ

(Continued from Page 9)

to get some sleep on the hard seat, for Pullmans

are unknown in Turkey, than I began

to make the acquaintance of the little travelers

who had put the itch into Anatolia.

They are the persistent little Nature guides

to discomfort.

For hours the country had become more

and more rugged. The fertile, lowlands

with their fields of waving corn and grateful

green were now far behind. As we

climbed steadily into the hills we could see

occasional flocks of Angora goats. It was a

dull, bleak prospect, but every inch of

ground, as far as the eye could see, and beyond,

had been f ought over.

At nine o’clock the next morning we

crossed a narrow stream that wound lazily

along. Although insignificant in appearance,

like most of the other historic rivers,

it will be immortalized in Turkish song and

tradition. In all the years to come the

quaint story-tellers whom you find in the

bazaars will recount the epic story of what

happened along its rocky banks. This

inconsequential-looking river was the famous

Sakaria, which marked the high tide

of the Greek offensive and the place where

Kemal Pasha’s army made its last desperate

stand. Very near the point where we

crossed, the Greeks were hurled back and

their offensive broken. What the Marne

means to France and the Piave to Italy,

that is the Sakaria to the new Turkey. It

marks the spot where rose the star of hope.

Almost before I realized it a pall of

smoke, the invariable outpost of a city,

loomed ahead. Then I saw scattered

mosques and minarets stark and white in

the sunlight, and before long we were in

Angora. The railway station is in the outskirts

of the town and I had to drive for

more than a mile to get to my lodging.

Despite the discomforts of the trip I

must confess to something of a thrill when

I stepped from the train. At last I was in

a capital without: precedent, perhaps, in

the history of civilization. After their

temporary sojourn first at Erzerum and

then at Sivas, the Kemalists had set up

their governmental shop in this squalid,

dilapidated and half-burned village at one

railhead of the Anatolian road. It was not

without its historical association because

once the crusaders camped here, and later

Tamerlane the Terrible had overwhelmed

the Sultan Bayezid in a famous battle and

carried him off to the East as prisoner.

Angora, the Strange Capital

Almost overnight the population had

grown from ten thousand to sixty thousand.

With the advent of the Grand National

Assembly, as the Turkish parliament is

called, came the cabinet, all the members

of the government, and the innumerable

human appendages of national administration.

Until the overthrow of the Greeks

last year, Angora was also the general headquarters

of the Turkish Army and its chief

supply base.

Then, as now, Angora was more like a

Western mining town in the first flush of

a boom than the capital of a government

whose future is a source of concern in

every European chancellery. Every house,

indeed every excuse for a habitation, is

packed and jammed with people. Imbrie,

the American consul, was forced to live for

a year in a freight car which was placed at

his disposal by the government. Moreover,

he had to struggle hard to hang on to

this makeshift home. The shops are primitive,

and there are only two restaurants

that a European could patronize.

Hotels as we know them do not exist.

The nearest approach is the so-called han,

which is the Turkish. word for house.

The average Turkish village han for travelers

is merely a whitewashed structure

with a quadrangle, where caravan drivers

park their mules or camels at night and sleep

upstairs on platforms. It is full of atmosphere,

and other things more visible.

If you have any doubt about the patriotism

which animates the new Turkish

movement you have only to go to Angora

to have it dispelled. Amid an almost indescribable

lack of comfort you find high

officials, many of them former ambassadors

who once lived in the ease and luxury of

London, Paris, Berlin, Rome or Vienna,

doing their daily tasks with fortitude.

‘ Happily I had taken out some insurance

against the physical discomfort that is the

lot of every visitor to Angora. After

Kemal’s residence, about the only one fit

to occupy is the building remodeled for

the use of the Near East Relief workers,

which had lately been acquired by the

representatives of the Chester Concession.

Before leaving Constantinople I got permission

to occupy this establishment, and

it was a godsend in more ways than one.

By some miracle, but due mainly to the

three old Armenian servants whom I kept

busy scrubbing the floors and airing the

cots, I had no use for my insect powder.

In fact I carried it back with me to Constantinople

and exchanged it for some other

and more aesthetic commodities.

This reference to the Chester Concession

recalls a striking fact which was borne in

upon me before I had been in Angora half

a day. Everybody, from the most ragged

bootblack up, not only knows all about the

concession but regards it as the unfailing

panacea for Turkish wealth and expansion.

Ask a Turkish peasant about it and he will

tell you that it means a railroad siding on

his farm next month. There is a blind, almost

pathetic faith in the ability of the

Chester concessionaires to work an economic

transformation. This is one reason

why in Angora as elsewhere in Turkey the

American is, for the moment, the favorite

alien. But the whole Chester matter will

be taken up in a later article.

Reasons for the Choice

By this time you will have asked the

question, Why did the Turks pick this

unkempt apology of a town as their capital?

The answer is interesting. The first consideration

was defense. Angora is more

than two hundred miles from the sea, and

any invading army, as the Greeks found

out to their cost, must live on the country.

Even in case of immediate attack there is

a wild and rugged hinterland which affords

an avenue of escape. But this is merely

the external reason.

If a Turk is candid he will tell you that

perhaps the real motive for all this isolation

is to keep the personnel of the government

out of mischief. At Constantinople the

official is on the old stamping ground of

illicit official intercourse. The Nationalist

Government is taking no chances during its

period of transition. It was Kemal Pasha

who selected Angora, and in this choice

you have a hint of the man’s discretion.

Although the Turks maintain that Angora

is the permanent seat of government and

that the unwilling foreign governments

must sooner or later establish themselves

there, it is probably only a question of

years until Constantinople will come back

to its own as capital. Meanwhile Angora

will continue to be the Washington of the

new Turkey, while Constantinople will be

its New York.

The principal thoroughfare of Angora is

unpaved, rambling, and the fierce sun beats

down upon its incessant dust and din. At

one end is a low stucco building flying the

red Turkish flag with its white star and

crescent. Here, after the personality of

Kemal, is what might be called the soul

of the Turkish Government. It is the seat

of the Grand National Assembly. In it

Kemal was elected president, and here the

Lausanne Treaty was confirmed.

Over the president’s chair hangs this

passage from the Koran: “Solve your

problems by meeting together and discussing

them.” In Kemal’s office just across

the hall is another maxim from the same

source, which says: “And consult them in

ruling.” In this last-quoted sentence you

have the keynote of Kemal’s creed, because

up to this time he has carefully avoided the

prerogatives of dictatorship, although to all

intents and purposes he is a dictator, and

could easily continue to be one, for it is no

exaggeration to say that he is the idol of

Turkey. His picture hangs in every shop

and residence.

The Grand National Assembly is unique

among all parliamentary bodies in that it

not only elects the president of the body,

who is likewise the executive head of the

nation, but it also designates the members

of the cabinet, including the premier. By

this procedure a government cannot fall,

as is the case in England or France, when

the premier fails to get a vote of confidence.

If a cabinet minister is found undesirable

he is removed by the legislative body, a

successor is named, and the business of the

government goes on without interruption

WE leave it to you I You know from your

own experience what damage is done

to your floors, carpets, rugs and furniture

every year by casters that do not roll and

turn easily. Torn carpets, scratched floors.

strained furniture come from dragging furniture

about—extra effort for you and increased

household costs.

Cut down these costs with

Bassick Casters!

Protect your floors and furniture with these

perfect rolling and easy turning casters. So

convinced are we that one set of four

All

four

for this

coupon

and

She Herself Would

Choose This Gift

A WHITING & DAVIS Mesh

Bag embodies the gift qualities

that touch every feminine

fancy—style, beauty,

usefulness.

He who would avoid the commonplace

should select this

Princess Mary Sunset—an exquisite

design radiating the

delicate blending of red gold,

green gold and platinum colors.

A fastidious gift for birthdays,

weddings, anniversaries. Your

leading jeweler or jewelry department

is now showing this

and other charming WHITING

& DAVIS Mesh Bags.

WHITING & DAVIS COMPANY

Plainville Norfolk County Massachusetts

yifts ‘That st”

03,10a–A–vign

Bassick Casters in your home will make you

realize the dollars that complete equipment

of these casters will save, that we are giving

a trial set at 25% under the regular price.

Don’t Miss this Special

Trial Offer

We offer you for sixty days a complete set

of four Handsome Bassick Wizard Swivel

Brass Plated Casters for medium weight

wooden furniture on carpets, rugs or linoleum,

at the remarkable price of 35c per

set (regular retail price 50c) or a set of

four Diamond Velvet Red Fibre de luxe

Casters for 75c per set (regular price $1.00).

Only one set can be sent to any one person.

Remember this is a trial offer only. Send

for your set now!

Bassicx Casters 011-,’ /

Fill out

coupon, en- / THE

close 35c or 75c. BASSICK

money order or COMPANY

stamps, sign name Bridgeport

and address plainly / Conn.

and mail today. Mon- / Please send me, deey

returned if not / livered free, one set of

satisfied.

/ Wizard Swivel Casters

/ Diamond Velvet

/ as advertised, for which 35c

/ I enclose . . 5 75c

/ Name

Address_

S. E. P.

3

,Davis j esil Bags

‘ In the Better Grades. Made of the Famous-Whiting-Soldered Mesh

How many DOLLARS

will this 35c Save?

I.

“(The Clifton”

73eautiful shades in soft, rich and

mellow textures. Conservatively

smart. Expertly fashioned (ilk) all

SCHOBLE HATS

for Style for Service

FRANK SCHOBLE & CO. Philadelphia

,.-<

ttt : .+:4it ti / .; .-..;.’

-1111: -il ii + i k i J, 4

ifif – , ffii izlti .,,

-Ifft ff il Iliti4k.-t‘

11 I’ p you would be the local rreepp– 4-

resentative for this, the larg-

11 I 1 ±

F4 est publishing company in the

world—if you would make, as

do literally hundreds of our subscription

workers, up to $1.50

an hour in your spare time,

send now the coupon below.

THE CURTIS PUBLISHING COMPANY

THE CURTIS PUBLISHING COMPANY

460 Independence Square, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Gentlemen: While I assume no obligation in asking, I should like to know all about your cash

offer to local representatives.

Name

Street

City State

14 2

THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

October 20,1923

The delegates to the Assembly are, of

course, elected by the people.

But all this is by way of introduction. I

was in the ken of Kemal and the job now

was to see him. I had arrived at noon on a

Wednesday and promptly sent Reschad

Bey to see Rauf Bey, the premier, to whom

I had a letter of introduction from Admiral

Bristol. The cabinet was in almost continuous

session on account of the crisis at

Lausanne, and I was unable to see him

until the following morning at nine.

I spent three hours with him in the

foreign office, a tiny stucco building meagerly

furnished, but alive with the personality

of its chief occupant. Rauf Bey is

the sailor premier—he was admiral of the

old Turkish Navy—and has the frank,

blunt, wholesome manner of the seafaring

man. He is the only member of the cabinet,

by the way, who speaks English, and he

told me that he had visited Roosevelt at the

White House in 1903. He was one of the

prominent Turks deported by the British

to Malta in 1920. In exile, he said, his

chief solace was in the intermittent copies

of THE SATURDAY EVENING POST which

reached him through friendly naval officers.

He had read these magazines so thoroughly

that he quoted long extracts from them.

He had been particularly interested in an

article of mine about General Smuts, whose

ideal of self-determination has helped to

shape the new Turkish policy.

It was Rauf Bey who made the appointment

for me to see Kemal Pasha at his

house on the following afternoon at five

o’clock. The original plan was for both of

us to dine there that evening. Subsequently

this was changed because, as Rauf

Bey put it, “The Ghazi’s in-laws are visiting

him, and his house is crowded.” By

using the term “in-laws” you can see how

quickly Rauf Bey had adapted himself to

Western phraseology.

The premier’s reference to the Ghazi requires

an explanation. Ordinarily Kemal is

referred to in Angora by the proletariat as

the Pasha. The educated Turk, however,

invariably gives him his later title of

Ghazi, voted by the assembly, which is the

Turkish word for “conqueror.” Since that

fateful day in 1453 when Mohammed the

Conqueror battered down the gates of Constantinople

and the Moslem era on the

Bosporus began, the proud title has been

conferred on only three men. One was

Topal Osman Pasha, the hero of Plevna;

the second was Mukhtar Pasha, the conqueror

of the Greeks in the late ’90’s, while

the third was Mustapha Kemal.

Friday, the thirteenth, came and with it

the long-awaited interview with Kemal. He

lives in a kiosk, as the Turks call a villa, at

Tchau Kaya, a sort of summer settlement

about five miles beyond Angora. Motor

cars are scarce in Angora, so I had to drive

out in a low-necked carriage. Reschad Bey

went along. He was not present at the

talk with Kemal, however.

The Ghazi’s Residence

As we neared Kemal’s abode we began

to encounter troops, who increased in numbers

the farther we went. These soldiers

represented one of the many precautions

taken to safeguard Kemal’s life because he

is in hourly danger of assassination by some

enraged Greek or Armenian. Several attempts

have already been made to shoot

him, and in one instance his companion, a

Turkish officer, was seriously wounded by

the would-be assassin.

Two previous Turkish leaders, both of

them tools of the Germans, the notorious

Talaat Pasha and his mate in crime, the no

less odious Enver Pasha, met violent deaths

after the World War. But Kemal represents

a different kind of stewardship.

Soon an attractive white stone house,

faced with red, surmounting a verdant hill,

and surrounded by a neat garden and

almond orchard, came into view. At the

right was a smaller stone cottage. Reschad

Bey, who had been there before, informed

me that this was Kemal’s establishment,

which was the gift of the Turkish nation.

I might have otherwise known it because

the guard of sentries became thicker. When

we reached the entrance we were stopped

by a sergeant and asked to tell our business.

Reschad Bey told the man that I had an

appointment with the Ghazi and he took

my card inside.

In a few moments he returned and escorted

us into the little stone cottage, which

Kemal uses as a reception room. Here I

found the Ghazi’s father-in-law, Mouammer

Ouchakay Bey, who is the richest

merchant of Smyrna and who incidentally

was the first Turkish member of the New

York and New Orleans cotton exchanges.

He had visited America frequently and

therefore spoke English. He told me that

Kemal was engaged in a cabinet meeting

and would see me shortly.

Meanwhile I looked about the room,

which was filled with souvenirs of Kemal’s

fame and place in the Turkish heart. On

one wall was the inevitable Koran inscription.

This one read, “God has taught the

Koran.” There were various memorials

beautifully inscribed on vellum, expressing

the homage of Turkish cities, and also magnificent

jeweled gift swords. But what impressed

me most was the life-size portrait

of a sweet-faced old Turkish woman that

had the most conspicuous place in the

chamber. I knew without being told that

this was Kemal’s mother. It was on her

grave that he swore vengeance against the

Greeks, who had once driven her out of her

home. I had heard this tale many times,

and Mouammer Bey and others confirmed

it. Happily for the mother, she lived long

enough to see her son the well-beloved of

the Turkish people.

Kenzal’s Steely Eye

I had just launched into a discussion of

the Turkish economic future with Mouammer

Bey when Kemal’s aid, a well-groomed

young lieutenant in khaki, entered and said

that the Ghazi was ready to see n e. With

him I crossed a small courtyard, went

down a narrow passage, and found myself

in the drawing-room of the main residence.

It was furnished in the most approved

European style. In one corner was a grand

piano; opposite was a row of well-filled

bookcases, many of the volumes French,

while on the walls hung more gift swords.

In the adjoining room I could see a group

of men sitting around a large round table

amid a buzz of rapid talk. It was the Turkish

cabinet in session, and they were discussing

the latest telegrams from Lausanne,

where Ismet Pasha, minister of foreign

affairs, and the only absent member, had,

only the day before, delivered the Turkish

ultimatum on the Chester Concession and

the Turkish foreign debt. Economic war,

or worse, hung in the balance.

As I advanced, Rauf Bey came out and escorted

me into the room where the cabinet

sat. There was a quick group introduction.

I had eyes, however, for only one person.

It was tke tall figure that rose from its

place at the head of the table and came

towards me with hand outstretched. I had

seen endless pictures of Kemal and I was

therefore familiar with his appearance. He

is the type to dominate men or assemblages,

first by reason of his imposing stature, for

he is nearly six feet tall, with a superb chest,

shoulders and military bearing; then by the

almost uncanny power of his eyes, which

are the most remarkable I have ever seen

in a man, and I have talked with the late

J. P. Morgan, Kitchener and Foch. Kemal’s

eyes are steely blue, cold, stony, and as

penetrating as they are implacable. He has

a trick of narrowing them when he meets a

stranger. At first glance he looks German,

for he is that rare Turkish human exhibit, a

blond.

His yellow hair was brushed back straight

from the forehead. The lack of coloring

in his broad face and the high cheek

bones refute the Teutonic impression. He

really looks like a pallid Slay. Few people

have ever seen Kemal smile. In the two

hours and a half that I spent with him his

features went through the semblance of relaxation

only once. He is like a man with

an iron mask, and that mask is his natural

f ace.

I expected to find him in uniform. Instead

he was smartly turned out in a black

morning coat with gray striped trousers

and patent-leather shoes. He wore a wing

collar and a blue-and-yellow four-in-hand

tie. He looked as if he was about to pay his

respects to a fashionable hostess at a reception

in Park Lane, London, or Fifth Avenue,

New York. Kemal, I might add, has always

been a stickler for dress. He introduced the

calpac, the high astrakhan cap which has

succeeded the long-familiar red fez as the

proper Turkish headgear, and which is a

badge of Nationalism.

Rauf Bey introduced me to Kemal in

the cabinet room. After we had exchanged

the customary salutations in French he

said, ” Perhaps we had better go into the

next room for our talk and leave the cabinet

to its deliberations.” With this he led

(Continued on Page 144)

Zfee!7,

SHOES

DR Ul D—a three-strap model

in the newest mode, shown at

Queen Quality agencies in softtoned

Autumn Brown Probuck,

and made with welt sole and

rubber-top walking heel. $8.50

Your Surety of Satisfaction

TO the pleasure you feel in authentic style— chic,

new, and always in keeping with your requirements—

Queen Quality shoe creations add all the niceties of

correct design, fine materials and tested fitting

quality—the essence of satisfaction in footwear. On

every pair the Queen Quality name is your surety—

the pledge of satisfaction to every wearer.

Queen Quality Styles for Women

Queen Quality “Osteo-Tarsal”, Flexator Unlocked

Shank (pat.), Walking Shoes forWomen and Children

Little Queen Styles for Misses and Children

An illustrated booklet of selections from the many new

ueen twilit), styles for women, misses and children will

be mailed on request.

THOMAS G. PLANT COMPANY

89 Bickford Street, Boston, 20, Mass.

This

Tn.de Mark

is your assurance of

Perfect Style

Perfect Fit

Perfect Service

Pesfect Satisfadion

Can You Afford to Pass Up

ThisCashOffer?

The

Curtis

Publishing

Company

482 Independence

Square, Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania

Gentlemen: Please send

me your cash offer. I don’t

promise to accept it, but I want

to see what it’s like.

Nome

Street

Town

UNLESS you have all the money you

want you can’t. For we will pay

you liberally in cash, month after month,

for easy, pleasant work that need not

take one minute from your regular job.

Your profits will be just so much extra

money—to help with regular expenses,

to buy things you want that you can’t

quite afford—to squander, if you like.

$100.00 Extra

Before Christmas

Right now many local subscription representatives

of The Saturday Evening Posl,The Ladies’

Home Journal and The Country Gentleman

are saving their earnings to buy Christmas

gifts. The commissions and bonus

that we pay them will, in literally

scores of cases, amount to over

$100.00 between now and the

time when the presents

must be bought. And a

hundred extra dollars

will buy a lot of

worthwhile gifts 1

No experience Yet

He Earned $98.90

His First Month.

Harry E. Hutchinson, of New

Jersey, began work about the

middle of October, 1914. By the

end of November he had earned

$98.90—and he has had easy

extra dollars every year since.

FREE Supplies, Equip.

ment, Instruction

You need not invest a penny. We tell you

HOW to make money, supply everything

you need to do it. and pay cash from the

moment you begin work. A two-cent

stamp brings our big fall offer—no

obligation involved.

’44 THE SATURDAY EVENING POST October 20,1923

(Continued from Page 142)

the way into the adjacent salon. With Rauf

Bey at my right and Kemal on the left, we

sat down at a small table. A butler, no less

well groomed than his master, brought the

inevitable thick Turkish coffee and cigarettes.

The interview began.

Although the Ghazi knows both French

and German, he prefers to talk Turkish

through an interpreter. After I had expressed,

again in my alleged French, the

great pleasure I had in meeting him, Rauf

Bey interposed the statement that perhaps

it might be best for the great man to carry

on in his own language. This was agreed

upon, and henceforth the premier acted as

intermediary.

Kemal had somehow heard of the difficulties

and delays which had attended my

trip to Angora. He at once apologized, saying

that in the handicaps that beset administration

in such a place as Angora such

things were liable to happen. Then he

added, “I am very glad you came. We

want Americans in Turkey, for they can

best understand our aspirations.”

Then, straight from the shoulder, as it

were, and in the concise, clear-cut way he

has of expressing himself —it is almost like

an officer giving a command—he asked,

” What do you want me to tell you?”

“First of all,” I replied, “can you give

me some kind of message to the American

people?”

There was method in this query because

I knew that he felt friendly toward Americans

and that it would immediately loosen

the flow of speech. It is a maneuver in interviewing

taciturn people that seldom

fails to launch the talk waves.

Rdmiration for Washington

Without the slightest hesitation—and

I might add that throughout the entire

conversation he never faltered for a reply—

he said:

” With great pleasure. The ideal of the

United States is our ideal. Our National

Pact, promulgated by the Grand National

Assembly in January, 1920, is precisely

like your Declaration of Independence.

It only demands freedom of our Turkish

land from the invader and control of our

own destiny. Independence, that is all.

It is the charter and covenant of our people,

and this charter we propose to defend at

any cost.

“Turkey and America are both democracies.

In fact the Turkish Government at

present is the most democratic in the world.

It is based on the absolute sovereignty of

the people, and the Grand National Assembly,

its representative body, is the

judicial, legislative and executive power.

Between Turkey and America as sister

democracies there should be the closest relations.

” In the field of economic relations Turkey

and the United States can work together to

the greatest mutual advantage. Our rich

and varied national resources should prove

attractive to American capital. We welcome

American assistance in our development

because, unlike the capital of any

other country, American money is free

from the political intrigue that animates

the dealings of European nations with us.

In other words, American capital does not

raise the flag as soon as it is invested.

“We have already given one concrete

evidence of our faith and confidence in

America by granting the Chester Concession.

It is really a tribute to the American

people.

“All my life I have had inspiration in the

lives and deeds of Washington and Lincoln.

Between the original Thirteen States and

the new Turkey is a curious kinship. Your

early Americans threw off the British yoke.

Turkey has thrown off the old yoke of empire

with all the graft and corruption that

it carried, and what was worse, the selfish

meddling of other nations. America struggled

through to independence and prosperity.

We are now in the midst of travail

which is witnessing the birth of a nation.

With American help we will achieve our

aim.”

Then leaning forward, and with the only

animation he displayed throughout the

whole interview, he asked:

“Do you know why Washington and

Lincoln have always appealed to me? I

will tell you why. They worked solely for

the glory and emancipation of the United

States, while most other Presidents seemed

to have worked for their own deification.

The highest form of public service is unselfish

effort.”

“What is your ideal of government?”

I now asked. ” In other words, do you still

believe in Pan-Islam and in the Pan-

Turanianism idea?”

“I will tell you briefly,” was the response.

” Pan-Islam represented a federation based

on the community of religion. Pan-

Turanianism embodied the same kind of

community of effort and ambition, based on

race. Both were wrong. The idea of Pan-

Islam really died centuries ago at the gates

of Vienna, at the farthest north of the Turkish

advance in Europe. Pan-Turanianism

perished on the plains of the East.

“Both of these movements were wrong

because they were based on the idea of conquest,

which means force and imperialism.

For many years imperialism dominated

Europe. But imperialism is doomed. You

find the answer in the wreck of Germany,

Austria, Russia, and in the Turkey that

was. Democracy is the hope of the human

race.

” You may think it strange that a Turk

and a soldier like myself who has been bred

to war should talk this way. But this is

precisely the idea that is behind the new

Turkey. We want no force, no conquest.

We want to be let alone and permitted to

work out our own economic and political

destiny. Upon this is reared the whole

structure of the new Turkish democracy,

which, let me add, represents the American

idea, with this difference—we are one big

state while you are forty-eight.

“My idea of nationalism is that of a people

of kindred birth, religion and temperament.

For hundreds of years the Turkish

Empire was a conglomerate human mass in

which Turks formed the minority. We had

other so-called minorities, and they have

been the source of most of our troubles.

That, and the old idea of conquest. One

reason why Turkey fell into decay was

that she was exhausted by this very business

of difficult rulership. The old empire was

much too big and it laid itself open to trouble

at every turn.

“But that old idea of force, conquest and

expansion is dead in Turkey forever. Our

old empire was Ottoman. It meant force.

It is now banished from the vocabulary.

We are now Turks—only Turks. This is

why we want a Turkey of the Turks, based

on that ideal of self-determination which

was so well expressed by Woodrow Wilson.

It means nationalism, but not the kind of

selfish nationalism that has frustrated selfdetermination

in so many parts of Europe.

Nor does it mean arbitrary tariff walls and

frontiers. It does signify the open door to

trade, economic regeneration, a real territorial

patriotism as embodied in a homeland.

After all these years of blood and

conquest the Turks have at last attained a

fatherland. Its frontiers have been defined,

the troublesome minorities are dispersed,

and it is behind these frontiers that we

propose to make our stand and work out

our own salvation. We propose to be

masters in our own house.”

Kemal’s Constructive Program

Again he leaned toward me and said in

his sharp staccato fashion:

“Do you know what has obstructed European

peace and reconstruction? Simply

this—the interference of one nation with another.

It is part of the selfish grasping nationalism

to which I have already referred.

It has led to the substitution of politics for

economics. The German reparations tangle

is only one example. The curse of the world

is petty politics.

“There are nations who would block our

hard-won Turkish independence; who decry

our nationalism and say it is merely a

camouflage to hide the desire for conquest

of our neighbors on the east, and who maintain

that we are not capable of economic

administration. Well, they shall see.

“The first and foremost idea of the new

Turkey is not political but economic. We

want to be part of the world of production

as well as of consumption.”

” What specific aid can the United States

render this new Turkey of yours?” I asked.

“Many things,” came from the blond

giant at my left. “Turkey is essentially a

pastoral land. We must stand or fall by

our agriculture. In the program for regeneration

three main activities stand out.

They are agriculture, transportation and

hygiene, for the death rate in our villages is

appallingly large.

“First take agriculture. We must develop

a whole new science of farming, first

through the establishment of agricultural

schools, in which America can help; second

It’s a far cry from Robinson Crusoe’s ‘ugly, clumsy,

goatskin umbrella” to the good-looking India—easy

to carry and efficient in the roughest weather.

The Man’s India—like the Woman’s India of equal

fame—has these exclusive features that put it far

ahead of the “ordinary” umbrella—

Distinctive shape and comfortable carrying length

Ten ribs instead of eight

Windproof tips that “spill” the wind

Greater protection afforded by wider spread

Longer service assured by sturdy construction

The India gives you more for your money. From

$2.00 to $50.00—it pays to insist on an India.

Manufactured by

ROSE BROTHERS. COMPANY, Lancaster, Pa.

and in Canada by THE BROPHEY UMBRELLA CO., Toronto

a$7/dia Umbrella Ouarantood

“The little umbrella with the big spread”

I ndi as for men, women, children and for travelers

boy the

Charming

Jail Bride

a azusca Tear is

At ?Our Jeweler’s

SUMATRA PEARLS

Beautiful pearls of delicate hues

and rich lustre. With white gold

diamond clasp and gray velvet

jewel case 24 inch graduated.

$35.00

Accompanied ha Bride book for the

recording of WeddingDayMemories

• Other La Tausca Necklaces up to boo

THE SJITURD.RY EVENING POST

145

through the introduction of tractors and

other modern farm machinery. We must

develop new crops, such as cotton, and

expand our old ones, such as tobacco. The

motor, whether on the highway or the farm,

will be our first aid.

“Transportation is equally vital. Before

the World War the Germans had laid out a

comprehensive scheme of transportation for

Turkey, but it was based upcn economic

absorption of the country by them. Happily

we are rid of the Germans, and so far

as I am concerned, they will never get back

to authority. We look to America to develop

our much-needed railroads. This is

one reason why we gave them the Chester

Concession. I hope that the Americans

realize what this concession means to us.

It is not only the hope of adequate transport,

but the building of new ports and the

exploitation of our national resources,

principally oil.

“In the matter of hygiene we have already

installed a ministry of sanitation as

part of the cabinet and every effort will be

made to prevent the infant mortality. Here

America can again help.

“While I am on the matter of economics

let me deal with another question of vital

importance to the new Turkey. The

tragedy of Turkey in the past was the

selfish attitude of the great European

powers towards one another in respect of

her commercial development. It was the

inevitable result of the great game of concession

grabbing. The powers were like

dogs in a manger. If they failed in their

desires they made it their business to keep

rivals out as well. It is precisely what has

been going on in China for years, but they

will make no China out of Turkey. We

will insist upon the open door for everybody,

as it was enunciated by John Hay, and

equality of opportunity for all. If the European

powers do not like this procedure

they can keep out.”

“What is your panacea for the present

world malady?” I next asked.

“Intelligent cooperation and not unintelligent

suspicion and distrust,” was the

swift retort.

“Is the League of Nations the remedy?”

I continued.

“Yes and no,” came from Kemal. “The

League’s error lies in that it sets up certain

nations to rule, and other nations to be

ruled. The Wilsonian idea of self-determination

seems to be strangely lost.”

When I asked Kemal if he was in favor of

allying Turkey with the League of Nations

he answered:

“Conditionally, but the League as at

present operated remains an experiment.”

On two significant subjects Kemal has

views of peculiar interest. They are Germany

and Bolshevism.

II Subtle Game

I am betraying no confidence when I say

that long before the Great War, which

proved so costly to his. country largely because

of German conspyacy, he persistently

opposed the German intrigue at Constantinople.

It was his violent objection to

everything German that caused Enver

Pasha, who with Talaat Pasha divided the

mastery of government during the war, to

seek to break him in the army service and

get him out of the way.

Instead of ending Kemal’s career Enver

provided him with the means of redeeming

Turkey and making himself the national

hero. Kemal’s antagonism to the Germans

today is no less pronounced.

With the Bolshevists Kemal played a

subtle and winning game. In the early days

of the Nationalist movement he had urgent

need of arms and munitions. He angled

with Moscow until he got what he wanted

in the shape of supplies, and then gave

them the cold shoulder. At that time the

Bolshevists looked upon the new Turks as

heaven-born allies for the red conquest of

the whole Near East. They were the first

to recognize the Angora Government, and

still maintain an elaborate mission there.

Kemal and his chief colleagues are convinced

that Bolshevism has passed the peak

and is on the down grade. If the ” Bolos ”

think that they have a willing tool in

Kemal they have another guess coming.

Upon one subject of universal interest,

the emancipation of Turkish women, Kemal

has definite opinions. He not only favors

the ultimate banishment of the veil but

wants woman to be part and parcel of the

public life. His views run in this wise:

“Our women ought to be the equal of

men in education and activity. From the

earliest times of Islam there have been

women savants, authors and orators, as well

as women who opened schools and delivered

lectures. The Moslem religion even

orders women to educate themselves to the

same standard as men. In the war with the

Greeks Turkish women replaced the absent

men in all kinds of work at home, and

even undertook the transport of munitions

and supplies for the army. It was done in

response to a true sociological principle—

namely, that women should collaborate

with men in making society better and

stronger.

“It is supposed that in Turkey women

pass their lives in inactivity and in idleness.

That is a calumny. In the whole of Turkey,

except in large towns, the women work

side by side with the men in the fields, and

participate in the national work generally.

It is only in large towns that Turkish

women are sequestered by their husbands.

This arises from the fact that our women

veil and cloister themselves more than their

religion orders. Tradition has gone too far

in this respect.”

During the whole interview, save for the

two occasions when he leaned forward to

emphasize his points, Kemal had sat erect

in his chair, smoking cigarettes continually.

The only time there was the slightest

indication of a break in those stony features

was when we started to discuss more or less

personal affairs at the end of the talk, and

when I told him that I had not married

because ‘I traveled so much and that no

wife would stand such incessant action.

He thereupon said: “I have only lately

married myself.”

Madame Kemal

This naturally leads to the romance in

Kemal’s life. Like other men of iron he

has his one vulnerable point, and having

met Madame Kemal I can understand why

he succumbed. I heard the whole story at

first hand and in this fashion:

While we were in the midst of the interview

the butler entered and whispered

something in Kemal’s ear. Instantly he

turned and said, not without pride, “Madame

Kemal is coming down.”

A few moments later the most attractive

Turkish woman I had yet met entered—I

should say glided—into the room. She was

of medium height, with a full Oriental face

and brilliant dark eyes. Her every movement

was grace itself. Although she wore

a sort of non-Turkish costume—it was dark

blue—she had retained the charming headdress

which is usually worn with the veil

and which, according to the old Turkish

custom, must completely hide the hair.

The veil, however, was absent, for madame

is one of the emancipated ones, and some

of her brown tresses peeped out from

beneath the beguiling cover. A subtle perfume

emanated from her. She was a visualization

of feminine Paris literally adorning

the Angora scene.

Kemal presented me to his wife, employing

Turkish in the introduction. I addressed

her in French and she replied in

admirable English; in fact, she had a British

accent. The reason was that she had

spent some of her school life in England.

Later she studied in France. Madame

Kemal at once took her seat at the table

and listened to the cross examination of

her husband with interest.

Shortly after her arrival Kemal was summoned

into the next room, where the cabinet

was still in session, and during his

absence she told me the story of her life,

which is a charming complement to the narrative

of her distinguished husband’s more

strenuous career.

Her father, as I have already intimated,

is the richest merchant of Smyrna, which

has been for years the economic capital of

Turkey. Her name is Latife. To this must

be added the word hanum, which in Turkey

may mean either “Miss” or ” Mrs.” Thus

before her marriage she was Latife Hanum.

If she employed her full married name now

it would be Latife Ghazi Mustapha Kemal

Hanum.

During the early days of the Greek war

she was alternately in Paris and London.

In the autumn of 1921 she returned to

Smyrna, which was then in the hands of

the Greeks, who had imprisoned her father

and who eventually arrested her on the

charge of being a Turkish spy. She was

sentenced to detention in her own home

with two Greek soldiers on guard before

the door. Here she spent three months.

One day the Greek sentries suddenly

vanished. There was the bustle and din of

EXTRA MONEY

When movie thrillers, or the circus, or fall football games come along, the

boy in this picture (Paul Soeurs of Ohio) never has to ask dad for money.

With dimes and quarters jingling in his pocket every week, Paul can use

them any way he likes. More fun, too, when it’s his own money he’s

spending.

FOR YOU, TOO

Why don’t you try his money-making plan, and, like Paul, be sure of

next week’s movie show? You can do it easily if you sell The Saturday

Evening Post each Thursday afternoon to folks in your neighborhood.

Great fun, too, for we’ll help you get customers. Just send your name to

The Curtis Publishing Company, Sales Division

483 Independence Square Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Multiplying Man-pow er

To the man with pick and shovel the digging of holes

for telephone poles is a slow and arduous task. Under

favorable soil conditions three to five holes are for him

an average day’s work. Under adverse conditions perhaps

he can account for only one. When the hole is dug,

eight or ten men are required to raise the pole with pikes.

But the hole-borer with derrick attached, operated by

only three men, can erect as many as eighty poles a day,

releasing for other telephone work upwards of forty men.

Hundreds of devices to quicken telephone construction,

to increase its safety to the employee, and to effect economies

are being utilized in the Bell System. Experiments

are constantly being made to find the better and shorter

way to do a given job. Each tool invented for the industry

must be developed to perfection.

In the aggregate these devices to multiply man-power

mean an enormous yearly saving of time, labor and money

throughout the whole Bell System. Without them telephone

service would be rendered neither as promptly,

as efficiently nor as economically as it is to-day.

“BELL SYSTEM”

AMERICAN TELEPHONE AND TELEGRAPH COMPANY

AND ASSOCIATED COMPANIES

One Policy, One System, Universal Service,

and dl directed toward Better Service

10 DAYS’FREE TRIAL. Try it. test it yourself, then

decide. EASY MONTHLY PAYMENTS. So small

you will not notice them, 6-YEAR GUARANTEE with

every Shipman-Ward factory-rebuilt Underwood., a late

model, perfect machine that will give

you yelps of service.

FREE BOOS OF FACTS. Write today,

inside story about typewriter

business. typewriter rebuilding. how

we do it, our wonderful offer. Act now.

SHIPMAN-WARD MFG. CO.

2757 Shipman Bldg.

Montrose and Ravenswood Ares.

CHICAGO. ILL.

Ask forHorlick’s

The ORIGINAL Safe

Milk

and Malt

Grain Ext.

in powder, makes

The Food-Drink

for All Ages

Avoid Imitations— Substitutes

Malted Milk /

41#

SALESMEN WANTED

ICII a unique line of advertising novelties on a liberal

commission basis. Highest references required.

STANWOOD MANUFACTURING CO., 5 Tread Raw, Basis., Mass.

Clark’s Round the World and Mediterranean Cruises

Jan. 15th and Feb. 2nd, 1924; 122 days $1000 up;

65 days $600 up. Shore excursions included.

FRANK C. CLARK, Times Building, New York

146

THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

October 20, 1923

hasty retreat, and early the next morning

the conquering Turks rode into Smyrna. A

few days later Kemal entered in triumph

at the head of his victorious army. Let me

tell the rest in madame’s own naïve words,

which were:

“Although I had never met Mustapha

Kemal I invited him to be our guest during

his stay in Smyrna. I admired his courage,

patriotism and leadership, and he accepted

our invitation. I found that we had common

ideals for the reconstruction of our

country, and later we discovered that we

had something else in common. Not long

afterwards forty to fifty of our friends were

invited to the house for tea. The mufti, as

the Turkish registrar is called, was summoned,

and without any previous announcement

we were married. Our wedding ring

was brought to us later from Lausanne by

Ismet Pasha.”

Madame Kemal spoke with f rank admiration

about her husband. “He is not only a

great patriot and soldier but he is also an

unselfish leader,” she said. ” He has built a

system of government that can function

without him. He wants absolutely nothing

for himself. He would be willing to retire

at any time if he were convinced that his

ideal of the self-determined Turkey will

prevail.

“I am acting as a sort of amanuensis for

him. I read and translate the foreign

papers for him, play the piano when he

wants relaxation, and I have started to

write his biography.”

” What are your husband’s diversions?”

I asked.

He loves music and when he does find

time to read he absorbs ancient history,”

was the reply. Then pointing to three playful

pups that gamboled on the floor at our

feet she added: “I have also provided him

with these little dogs, to whom he has become

much attached.” The snapshot of

Kemal reproduced in this article shows

the pups.

Education Before Suffrage

Madame Kemal has definite ideas about

the future of Turkish women. Like Halide

Hanum, she is strong for emancipation.

Along this line she said:

“I believe in equal rights for Turkish

women, which means the right to vote and

to sit in the Grand National Assembly. I

maintain, however, that before suffrage

and public service must come education.

It would be absurd to impose suffrage on

ignorant peasants. We must have schools

for women eventually, conducted by

women. It is bound to he a slow process.

I am in favor of abolishing the veil, but

this will also be a gradual development.

We want no quick changes. It must be

evolution instead of revolution.

“On one subject I have strong views:

Education and religion in Turkey must be

separate and distinct. This is my ideal of

the mental uplift of the women of my race.”

We began to discuss books. Much to my

surprise I found that Madame Kemal was

a great admirer of Longfellow. She quoted

the whole of the Psalm of Life. I was

equally interested to find how well she

knew Keats, Shelley and Byron. I referred

to the fact that in the old days Byron’s

books were forbidden in Turkey on account

of his pro-Greek sentiments, whereupon

she remarked vivaciously, “All such procedures

are now part of the buried Turkish

past.”

At this juncture Kemal returned, and

the threads of the interview with him were

picked up. When we concluded, twilight

had come and it was time to go. I had

brought with me a photograph of the Ghazi

that I had obtained in Angora. It was

taken in the early days of 1920. As he

looked at it he said wistfully, “That reminds

me of my youth.” He signed it and

then gave me two others at my request.

The farewells were now said, and I left.

As I drove back to Angora through the

gathering night, hailed at intervals by cavalry

patrols, for the watch on Kemal increases

with the dark, and with bugle calls

echoing across the still air, I realized that I

had established contact with a strong and

dominating personality, a unique leader

among men.

It remains only to reveal the somewhat

brief and crowded span of Kemal’s life so

far. He is the son of an obscure petty government

official and was born forty-three

years ago at Saloniki, which was then under

the Turkish flag. The fact of his birth here

has given rise to the widespread belief that

he is a Jew, which is not true. The surmise

was natural because during the Spanish

persecutions Saloniki became the haven

of innumerable oppressed Israelites. Here,

as elsewhere in the Turkey that was, and

is, they have become important factors in

both the commercial and the political life.

The Turks are a mixed race, however, because

of the old itch for conquest, and

Kemal’s mother had a strain of Albania

in her.

Kemal was destined for the army and at

the proper age entered the military school

at Monastir. Once in the army, he impressed

his colleagues by a real love of

soldiering. Then, as now, he was a nationalist.

In those days this was heresy, because

Turkey was in the grip of a corrupt stewardship

which combined control of both church

and state in the sultanate. In other words,

the sultan was not only ruler but as grand

caliph was also defender of the faith.

A comrade of Kemal’s early soldiering

days told me in Constantinople that when

the Committee of Union and Progress,

which was controlled by Enver Pasha, and

which brought about the revolution of 1908

and the counter revolution of 1909, was at

the height of its power, the future emancipator

of his country said: “These politicians

are bound to fail because they

represent a class and not a country. Their

motives are purely political. Some day I

shall help to redeem Turkey.” Like Napoleon,

he believed that he was a man of

destiny, and his subsequent achievements

have confirmed that early belief.

Kemal at the Dardanelles

It is interesting to add that at a time