Would a country sacrifice more than 550 historical monuments from various Mesopotamian civilizations to a dam? It appears Turkey is determined to do just that. It is no joke. The Ilisu Dam project — under discussion since 1958, approved in 1982 and accelerated by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government in 2006 — will swallow Hasankeyf, a major juncture along the Silk Road.

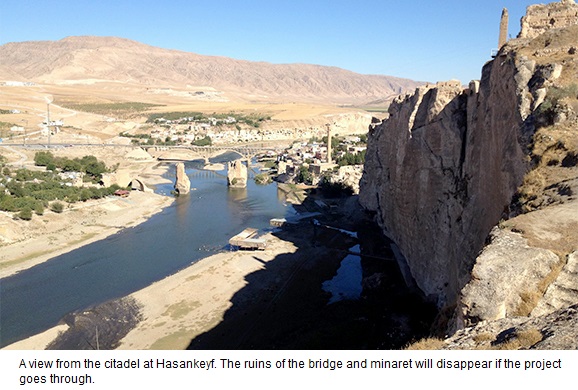

A town now condemned to death, Hasankeyf has seen Romans, Byzantines, Persians, Artuqids, Ayyubids, Aq Qoyunlus and Ottomans come and go. The sites destined to bid farewell to the world include a 12th-century double-deck stone bridge with only four feet surviving, the El Rizk Mosque, the Mardinike Palace ruins, the Zeynel Bey Mausoleum, the Syriac Quarter, the Sultan Suleyman Mosque, the Koc Mosque, the Inn and the Arasta bazaar, a number of shops and kilns, and countless cave dwellings. The Batman Municipality organized the Hasankeyf Culture and Arts Festival for Oct. 18–20 to draw attention to the looming disaster.

A president unmoved by ancient civilization

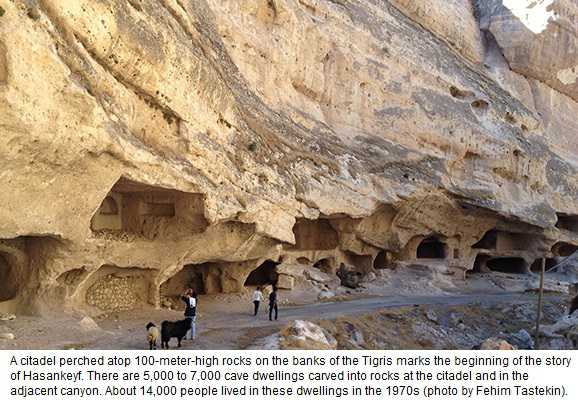

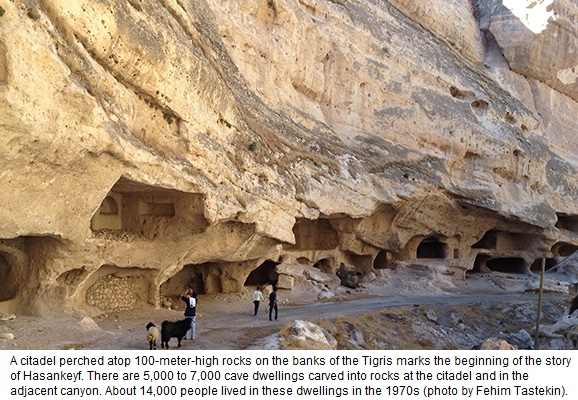

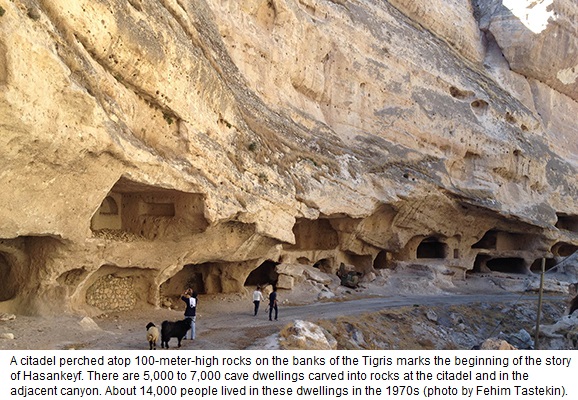

A citadel perched atop 100-meter-high rocks on the banks of the Tigris marks the beginning of the story of Hasankeyf. There are 5,000 to 7,000 cave dwellings carved into rocks at the citadel and in the adjacent canyon. Until the 1970s, the settlement remained alive as an ancient “citadel town,” with its mosques, churches, cemeteries, tombs and markets frozen in time. In 1966, President Cevdet Sunay happened to pass through the region and was appalled. “How could people still be living in caves? Homes should be built for them immediately!” The townsfolk were moved into houses built on the grounds the citadel overlooks. The old town is now derelict, in ruins.

Decades have passed, but, unfortunately, many are still of Sunay’s mindset, belittling the civilization of a rock-dwelling community as “living in caves.” In 2009, Yasar Agyuz, a main opposition lawmaker, submitted a parliamentary inquiry, asking the government whether it would “sacrifice Hasankeyf to a dam with a lifespan of 40–50 years.” The Environment Ministry defended the plan to annihilate a civilization, stating, “The water will submerge only ‘the lower town’ where structures are [already] destroyed.” Hasankeyf Mayor Abdulvahap Kusen, though a member of the ruling party, raised heartfelt objections. “We would not exchange our caves even for villas. We are against projects that would destroy history and culture,” he said.

A view from the citadel at Hasankeyf. The ruins of the bridge and minaret will disappear if the project goes through.

Why is sightseeing banned?

The culture and arts festival gave me the opportunity to tour Hasankeyf before it is flooded and joins the mythical club of “lost cities.” Visitors arriving in Hasankeyf, 37 kilometers from Batman, are greeted by the Zeynel Bey dome, which is famous for its tiles. The essential part of town is on the opposite bank of the Tigris. We passed through the exotic souvenir market at the entrance and reached the gate of the old town, where the guard lazing in the security booth stopped us:

“Going up to the citadel is forbidden.”

“Why?”

“A rock rolled down last year, killing three people. There is a ban now because it could happen again.”

We thus decided to take a break at a café perched on the hill. Accompanied by Batman Municipality Cultural Director Yunus Celik, we sipped Turkish coffee, boiled on cinders, while taking in the minaret of the 600-year-old El Rizk Mosque, destined to go underwater.

One of the café’s employees, Bilal, explained that the minaret, where storks now nest, would be submerged up to the level of its balcony. He dismissed the reason for the citadel ban, offering another explanation: “If the place remains out of the public eye, there will be no public awareness. That’s why they don’t want tourists.”

The world of Ali the shepherd

Ali the shepherd dropped in at the café just in time. He instantly recognized us as Hasankeyf visitors barred from sightseeing and made an offer: “My house is on the citadel. If you wait for a while, I’ll take you there.”

Ali is the only person who continues to live in one of the cave houses that the state evacuated. He is also an officially accredited tour guide. The ban, however, has made his business a “clandestine” affair. “Let me first read your coffee cups, and then I’ll show you around,” he said, before vanishing into thin air.

Bilal stepped in, offering to take us to the citadel via a clandestine route, so we breached the ban and sneaked in. Mi and Bizin, from Ali’s herd, joined us at the riverbank. I gave them these names: mi means “goat,” and bizin means “sheep” in Kurdish. We climbed the steps carved into the rocks and walked to the other side of the hill. To stop trespassers, the gate on the back side of the citadel has been encircled with a makeshift wall. Leaving Mi and Bizin behind, we resolutely climbed over the wall. The site is no longer a citadel, but rather a plateau of ruins.

Bilal pointed to the homes carved into the rocks at the citadel and the stone mosque and church. “There are at least 5,000 homes here. The water will rise to a height of at least 65 meters, submerging the homes in the valley. It will not reach the homes on the citadel, but they will eventually melt away because the rocks are so soft,” he said. Bilal showed as around the palace, the Ulu Mosque (converted from a church), a building that he described as the place where “the first-ever coins were made” and a mausoleum, where he said a prayer. He explained how residents used to get jars of drinking water up the hill with the help of a pressure mechanism.

As we climbed down from the citadel, Mi and Bizin were waiting for us. We went on climbing in the valley, where the mosque and church were. At a tomb carved in the rocks, we quaffed water that we drew from a well. Mi and Bizin were not forgotten.

Beyond the citadel, cave houses dot both banks of the valley. Pointing to a place in the middle that used to be a marketplace, Bilal said, “That was my grandfather’s barber shop.” He then returned to the subject of the rock that fell from the gate the Ayyubids had added to the citadel. “An excavation was under way. They were using sledgehammers, and the owner of the café up there warned them that a rock might roll down, but they didn’t listen. Then a rock did hurtle down and killed three people,” Bilal recalled.

As we finished our tour, completing a full circuit of the citadel, Bilal gave us a piece of advice: “If the officials ask any questions, don’t mention the citadel. Just tell them you went to the mausoleum to pray.” When we reached the entrance, it was Bilal who had to mollify the officials. There were no questions for us, nor for Mi and Bizin! The brief expedition into history left me profoundly shaken.

Why locals are uneasy

So, what happens next? Western financial institutions had managed to disrupt the Ilisu Dam project for a time, by refusing to grant loans for the dam after the issue was taken to the European Court of Human Rights. The current, ongoing construction, however, is financed through domestic funding. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has set 2014 as the deadline for completion.

Thus, the countdown for the people of Hasankeyf has begun. They have two options: to migrate or to move to a housing complex erected by the state Housing Development Administration (TOKI) along the skirt of the Raman Mountains, opposite the old town, an area spared from flooding. TOKI claims it has built the new Hasankeyf in the style of Artuqid architecture.

The locals are exasperated by life in a place deprived of investment for decades, first because the area was an archaeological site off-limits to construction, and then because of the anticipation that the area would be flooded anyway. “Incidents of snake and scorpion biting are commonplace here, but there is no doctor. Life is unbearable. The flow of tourists has died down since the citadel was closed,” Bilal said.

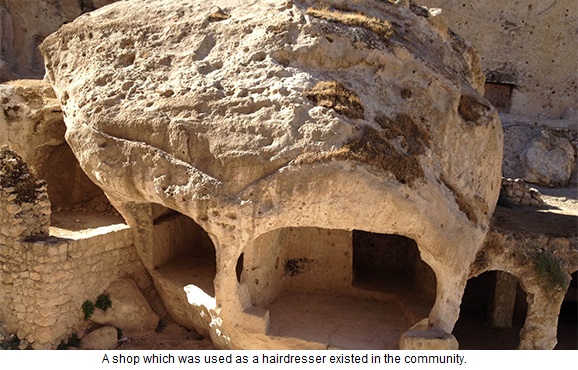

A shop which was used as a hairdresser existed in the community.

Initially, most Hasankeyf residents saw the dam project as a savior. For them, it meant cash and jobs, but the expropriation payments for their properties have been a disappointment. In addition, as construction has advanced, they have come to realize what a treasure they are about to lose. On Oct. 10, Hasankeyf residents held a demonstration blocking the bridge.

“My shop was valued at 7,000 Turkish lira [$3,500] and my house at 20,000 Turkish lira [$10,000]. They want me to move to the TOKI complex. The price of a house there is 180,000 Turkish Lira [$90,000]. So, they are telling me to contract a debt of 160,000 [$80,000],” grumbled a shopkeeper in the historic bazaar.

Before he disappeared, Ali the shepherd also expressed apprehension. “Fourteen thousand lived in the caves until the 1970s. Now I’m the only one. My parents lived with me until 2008. I was promised a house and jobs for my family, but none of the promises materialized. I’m accustomed to the history and climate up there. I can’t give it up,” he said. Ali believes there are still two ways to save history. “The bend and the dam lake could be kept away from Hasankeyf, or two dams could be constructed instead of one in order to have a lower water flow,” he said.

The Wise Men group that Erdogan formed as part of the Kurdish peace process has also recommended that the project be stopped or modified. “It should be taken into account that if Hasankeyf is declared a world historical heritage site, the revenues it will generate will far exceed the dam revenue. Thus, at least decreasing the water retention level must be considered to save the historical and natural riches,” the group said in a report on the issue.

The government, however, rules out investment in Hasankeyf’s heritage on the pretext of terrorism. The people of Hasankeyf counter that the area is free of “terrorism.” Radikal correspondent Serkan Ocak, who’s familiar with the issue, told Al-Monitor, “Some 10 to 15 year ago, the idea was to flood the caves and the passages on the grounds they were used by the PKK [Kurdistan Workers Party]. In order to save Hasankeyf, a proposal was made to build five small dams instead of a large one, but no one ever lent it an ear. They launched the construction even though the impact of terrorism has significantly subsided.”

Erdogan’s promise that the monuments would be relocated is met with a bitter smile among the locals. Hasankeyf is not just tombs and minarets. Moreover, experts have warned that moving the monuments would amount to smashing them into smithereens. As someone just back from Hasankeyf, I would only add this: The rock-dwelling civilization is silently crying out. It is high time to hear its voice.

By Fehim Taştekin

AL Monitor