by Steven A. Cook

April 23, 2013

“Recep Tayyip Erdogan is Turkey’s first Pharaoh!” a contact in Turkey declared to me recently over breakfast in Ankara. “Not a Sultan?,” I countered teasingly. “No, the Sultans had some checks on their power. Today Tayyip Erdogan’s power is absolute.” My friend, who would fall within the category of right-of-center nationalist, assured me that his Pharaoh comment was not meant to be an insult, but rather a statement of fact. That’s hard to believe given what the leaders of ancient (and not so ancient) Egypt stood for and the principles by which Erdogan and his associates claim to have governed Turkey for the last almost eleven years. Indeed, when Erdogan, Abdullah Gül, and the people around them broke from Turkey’s Islamist old guard and established the Adelet ve Kalkinma Partisi (Justice and Development Party, AKP) they offered Turks a vision of a democratic and prosperous Turkey.

Between 2002 and 2007, the Justice and Development Party, first under Abdullah Gül’s brief tenure as prime minister and then Erdogan, delivered on both. In those five years, the Turkish economy grew an average of over 6 percent annually and the AKP-dominated Grand National Assembly passed a range of significant political reforms that resulted in the European Union’s official invitation to begin negotiations to join that exclusive club of democracies. It seemed clear that by the time AKP won 47 percent of the vote in the July2007 elections, the Islamists (they prefer “conservative democrats”) had actually done what the country’s secular nationalists had only claimed to do—which was in the words of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, “raise Turkey to the level of civilization” through the modernization and democratization of Turkish political institutions. The AKP also invested in services for Turkey’s middle and lower classes, who value the advances in transportation and healthcare as much, if not more, than the successful efforts to subordinate the military to civilian leaders, for example.

Since 2007, however, AKP’s reform efforts have slowed and in some areas there have been notable reversals, especially when it comes to freedom of expression. Moreover, the party has become a machine par excellence with its connections to media outlets, business, and government contractors, which only bolster its monopoly on political power at the local and national levels. A decade after assuming power, Prime Minister Erdogan is the sun around which Turkish politics revolves—a fact he both knows and seems to relish. He seldom seems to wrestle with a decision, enjoys swatting away questions from observers who clearly “do not pay close enough attention,” and brooks no criticism from an opposition that he does not take seriously.

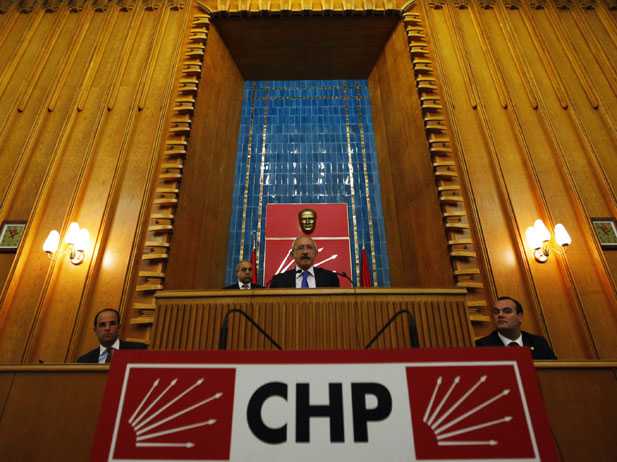

Of these, the latter is the most salient politically, but there is very little reason for Prime Minister Erdogan to give his primary opponents—the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP)—much in the way of respect. The CHP has 135seats in the Grand National Assembly and the MHP controls 53 mandates in the 550 seat parliament. These may seem like a lot, but the vote totals for both parties are confined to specific regions of the country (the Aegean coast and European parts of Turkey for the CHP and mostly Iğdir province for the MHP) whereas AKP has significant cross-regional appeal and thus enjoys a parliamentary majority of 327 seats. More importantly, while both parties have become adept at complaining about Prime Minister Erdogan and criticizing the AKP, they are unable to articulate an alternative vision for Turkey’s future. I have a good understanding of what the CHP and MHP are against, but I have a harder time understanding precisely what they are for. I’m willing to allow for the fact that I might be missing something in translation, but it seems that millions of Turkish voters are also confused.

The inability to offer Turks a vision goes hand in hand with what seems like a strong aversion to modernize their internal structures and political processes. Take the CHP, for example. As I was departing Turkey on Saturday, the papers reported that the party’s Deputy Chairman, Gülseren Onanç, was forced to resign. Ms. Onanç is a young, well-educated, successful businesswoman who was responsible for CHP’s public relations. Her crime? She appeared on a television program against the expressed wishes of party chairman Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu and dared suggest that 65 percent of the CHP’s grassroots support the government’s efforts to bring the war with the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (known as the PKK)—a terrorist group that has waged a campaign of violence in Turkey since 1984 that has cost 40,000 lives—to an end through negotiations. In other words, Onanç was doing her job, but in the CHP’s patriarchal politics, nothing happens unless Kiliçdaroğlu says so. It was not too long ago that analysts regarded Kiliçdaroğlu to be the savior of the CHP, which was reeling from a sex scandal and poor electoral performances. There have not been any more illicit videos of CHP officials, but further loss of momentum for the party has marked Kiliçdaroğlu’s tenure. On the substance of what Onanç said, it seems clear that the party leadership would rather censure one of its potential future leaders than take part in a process that may finally bring peace to Turkey. Either Kiliçdaroğlu and the people around him do not want to bring the conflict to an end because of an attachment to an ethnic based nationalism (a problem also among Kurdish opponents of peace) or they see it as a wedge issue. Either way, Onanç’s dismissal reflects a political party that has yet to come to grips with how much Turkey has changed. The old truths and myths no longer apply in a more complex and differentiated society whose people want more than the drab political conformity that Kemalism (and the CHP) demand. The AKP surely wants to take credit for Turkey’s transformation, but it was happening well before Erdogan and Gül defied their mentors way back in 2001.

This all brings us back to Erdogan and his alleged Pharaoh-ness. Not to diminish either Erdogan’s achievements or his faults but the desultory state of the opposition has no doubt contributed to his mastery of the political arena. I know Turks who don’t share AKP’s views on a variety of issues, but nevertheless vote for the party because they have no other real choice. Others choose not to vote. Without any viable options among the opposition an important check on Erdogan and the AKP does not exist, which does not bode well for the consolidation of democracy in Turkey. When journalists are jailed, corporations are punished with huge tax levies because their owners are deemed unfriendly to the AKP, and the courts are used to dole out political payback, it is the fault of Erdogan and his party’s other leaders whose authoritarian tendencies are clear, but it also the responsibility of Turkey’s other political parties who are all at once ineffective, insular, and feckless, rendering them trivial in Turkey’s fascinating transformation.

Leave a Reply