Ethiopians now also challenge the bogus Armenian claim to being the first nation to accept Christianity (in fact, the first one was the Kingdom of Edessa / Osroene, a Syriac state in the present-day Southeastern Turkey).

By Brendan Pringle

International Business Times | March 04 2013 10:19 AM

For centuries, historians have widely accepted the argument that Armenia was the first Christian nation. This important claim has become a source of national pride for Armenians and has remained virtually undisputed for centuries — until now.

Armenians will likely be up at arms when they learn that a new book — “Abyssinian Christianity: The First Christian Nation?” — is challenging their claim, presenting the possibility that Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea) was the first Christian nation.

To be sure, the book doesn’t conclusively assert that Ethiopia was the first nation to adopt Christianity as its state religion. However, it will surely challenge the confidence of modern Church historians with groundbreaking evidence.

The Weakness of Armenia’s Claim

Armenia’s claim on this meaningful title is primarily based upon the celebrated fifth century work of Agathangelos titled “The History of the Armenians.” In it, he says as an eyewitness that after the Armenian King Trdat III was baptized (c. 301/314 A.D.) by St. Gregory the Illuminator, he decreed Christianity was the state religion.

The truth is that we have no solid proof to support this account. We are forced to rely solely on the authenticity of Agathangelos and his contemporaries. These historians try to liken the conversion of Trdat III to that of Constantine’s, even though the baptism of Constantine is questionable, as was his own personal “conversion.”

Michael Richard Jackson Bonner, a linguist at Oxford University, contends that Agathangelos had a clear agenda. He “wished to stress the independence and uniqueness of the Armenian church … [and The History] is a tendentious compilation, which has expanded and elaborated earlier traditions … and greatly increased the prestige of the See of the patriarchs of the fifth century.”

In addition, recent studies date “The History of the Armenians” to c. 450 A.D., making it impossible for Agathangelos to have been an eyewitness. If Armenia’s claim is based on nothing more than oral history, how can it hold any more credibility than Ethiopia’s own Christian legends?

As for the spread of Christianity in Armenia, historian Peter Brown argued that “Armenia became a nominally Christian kingdom” after the king’s baptism. The Armenian people in fact “did not receive Christianity with understanding … and under duress.”

Where Ethiopia Differs

The Acts of the Apostles describe the baptism of an Ethiopian eunuch shortly after the death of Christ. Eusebius of Caesaria, the first church historian, in his “Ecclesiastical History,” further tells of how the eunuch returned to diffuse the Christian teachings in his native land shortly after the Resurrection and prior to the arrival of the Apostle Matthew.

Before the Ethiopian king Ezana, (whose kingdom was then called Aksum) embraced Christianity for himself and decreed it for his kingdom (c. 330 A.D.), his nation had already constituted a large number of Christians.

During the persecutions of Diocletian (284-305 A.D.), commerce ports like Adulis, along the Red Sea, served as a sanctuary for Christians in exile and the Christian faith began to grow rapidly in these areas. Pagans still comprised the religious majority at this time, but as historian Kevin O’Mahoney argued, the Christian faith first took root in “the upper social classes and gradually spread downwards to become the religion of the people.”

Such was the religious climate that St. Frumentius faced when his ship was pillaged by the native Ethiopians at the start of the fourth century A.D. The Ethiopian king spared his life, and Frumentius received a place of honor at the royal court. In this position, he nourished the Christian faith by locating Christians and helping them find places of worship. He also educated the king’s heir, Ezana, and converted him to Christianity.

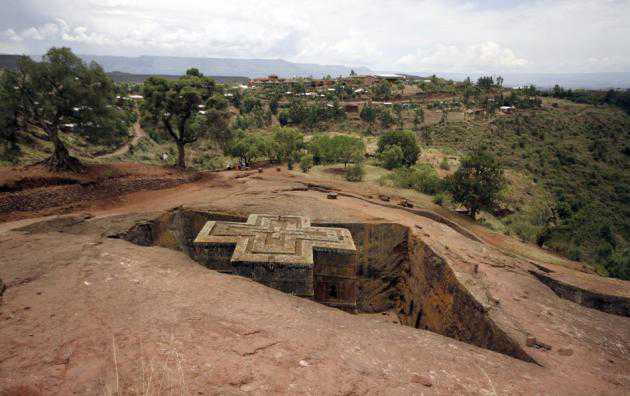

For this people, Ezana’s conversion became a public conversion for Aksum, and Christianity continued to serve as a point of reference for the nation. Unlike the case of Armenia, we have tangible proof of this conversion:

Historians have uncovered a public acknowledgement of the Christian faith from Ezana. Also, coins bearing Ezana’s image depict the cross after his conversion.

As the authors of “Abyssinian Christianity” conclude, “the promotion of the new faith developed into the single point of personal and public identification and unity for Abyssinians.” Christianity became the centralizing force behind the Ethiopian empire, which endured through 1974, despite religious and political threats from all sides.

Can a nation only become Christian if there is an official decree from its sovereign? If that were the case, then the Kingdom of Edessa would be the first Christian city-state (in modern terms) in c. 218. As we see with Abyssinia, and Israel before it, a nation isn’t confined to political boundaries. Rather, it is defined by a group of people who share a common heritage.

For the Ethiopians, this shared heritage was Christianity.

Brendan Pringle is a graduate of the National Journalism Center and the editor of “Abyssinian Christianity: The First Christian Nation?” For more details about the book, visit www.bp-editing.com.