Taboos are the target for Turkish cartoonistr

Izel Rozental treads a fine line with his political cartoons in an Istanbul weekly. The Turkish-Jewish cartoonist says buckling under pressure is out of the question – even when his critics are Turkey and Israel.

Izel Rozental treads a fine line with his political cartoons in an Istanbul weekly. The Turkish-Jewish cartoonist says buckling under pressure is out of the question – even when his critics are Turkey and Israel.

Cartooning always came naturally to Izel Rozental. He started sketching as a child – his mother, his family, and later when he started school he pointed his pen at his teachers and professors. That was the beginning of all the trouble, Rozental admits.

Most people don’t like to be turned into a caricature.

“Then you see how in trouble you are. And when they don’t like it, if you have inside yourself something, some cartoonist soul, then you feel that you have to draw and you continue, and that’s how it all begins,” Rozental smiles the way he probably did when his sketches were taken up in class. “And that’s how it started with me.”

Rozental contends that cartooning is tinged with anarchy, breaking rules and taboos and taking no sides.

It’s not an easy stance to take in Turkey right now. In October, the Turkish government was accused of clamping down on press freedom. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, a US-based NGO, 49 journalists are in jail in Turkey simply for what they wrote. That’s more than in any other country in the world.

Uncompromising from the start

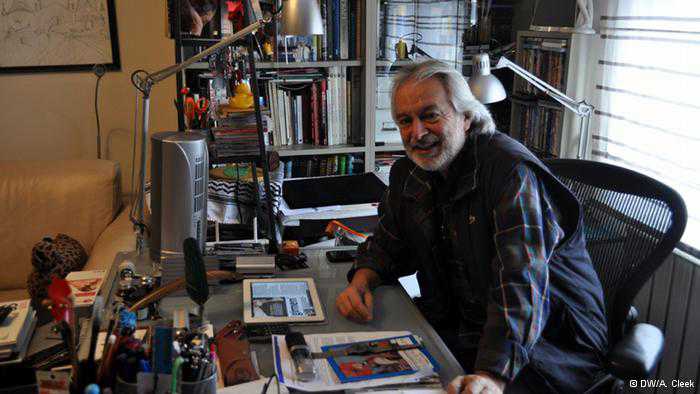

Rozental’s office is in a quiet neighborhood on Istanbul’s Asian side. Hundreds of books, randomly matched with small children’s toys and drawings, line an entire wall. His desk is barricaded on one side by cups of pens and bottles of ink, the weapon of a cartoonist, but also how Rozental made his living before cartoons – as a pen maker.

Rozental still has a company that makes writing instruments

Rozental still has a company that makes writing instrumentsAs a young man, Rozental served in the Turkish army – as all men in Turkey are still required to do – but even in the army, he continued to draw. He sent his cartoons home to his mother, instructing her to take them to the editors of leading cartoon magazines. When he came home 18 months later, he found his cartoons hanging on the walls of the house. His mother had kept them, fearing they would get her son in trouble.

So Rozental took them to the magazines himself, and two of his cartoons were accepted by Oguz Aral, the founder of one of Turkey’s most popular cartoon magazines, Girgir. But along with the acceptance and a check, Aral made a few corrections, in pencil, of how Izel’s cartoons could be improved.

His anarchist side started to protest, Rozental says.

He leans over and points to an image of one of the drawings on his iPad. “You see, with pencil he said, ‘Write this, don’t do this.’ And this is the money I didn’t take,” Rozental smiles, mischievously. He didn’t cash the check, and for the next few decades he didn’t publish anything.

Then, in 1991, during the First Gulf War, Shalom, the newspaper of Istanbul’s Jewish community, asked him to become their political cartoonist. His work has appeared on the paper’s front page ever since.

Beyond censorship

Most of Rozental’s cartoons have few words. Instead, they rely on caricature and bold juxtapositions to hone a fine point. One cartoon shows a train with a Turkish flag speeding down twisted, double-backed mountain passes, in a Sisyphean loop, while the European Union celebrates its birthday in the distance.

Rozental says he always finds a way to express criticism

Rozental says he always finds a way to express criticismRozental says he has felt constrained by censorship on a few occasions but has always found a way to speak his mind. He mostly draws what he wants. But every now and then, in the middle of the night his editors will call and ask him to change something.

“Sometimes, I receive a call at midnight, two o’clock in the morning, from the editor in chief, he’s asking me, ‘What is your cartoon about, can you explain a little bit, because we are getting confused, and we don’t want to get …”

He is sympathetic to their concerns: Publishing cartoons in a Jewish newspaper in Muslim Turkey is not easy.

“From time to time I accept that they [are] right, and I change my cartoon. But sometimes I cannot, and I say it must be like this. I say I am here to accept all the reaction from wherever it may come, and it comes. Sometimes from the Muslims, sometimes from the Jewish people, because they are also not very happy.”

He finds ways to push back. Not too long ago, it was illegal in Turkey to show the colors red, yellow, and green together because they could represent the Kurdish flag and the combination was alleged to be “anti-Turkish.” So, Rozental drew a rainbow and omitted those three colors.

He admits, however, that there are moments when the pressure becomes too much. At the beginning of the 2000s, during the Second Intifada, the beginning of a period of increased violence between Israel and Palestine, every cartoon Rozental drew was attacked from three sides: Israel, Turkey, and the Jewish community in Istanbul.

So Rozental stopped drawing people all together. Instead, he drew fish, small tropical fish in different colors, sometimes with simple, white thought bubbles. “Things that I cannot say in my cartoons, I say through my fish,” Rozental explains.

But the point, he says, is that a cartoonist must continue to say something, to criticize. He asserts that for a cartoonist, there should be no real taboos.

“[Cartoon