About the author

Firat Cengiz is lecturer in law at the University of Liverpool. Her primary research interests are in Europeanisation and multi-level governance. She is the author of Antitrust Federalism in the EU and the US and the co-editor of Turkey and the European Union: Facing New Challenges and Opportunities (with Lars Hoffmann).

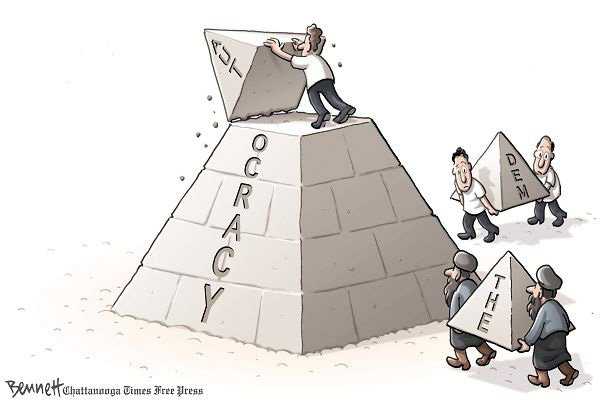

Constitutions are highly entrenched laws that express the common identity of the nation. They require substantial public involvement. Yet in Turkey, the details of the reform process have not been fully disclosed, and it is being rushed through.

Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan considers 2012 a lost year for his country’s democratic reform process. In an interview he recently he gave to the state TV channel TRT, Erdoğan expressed frustration that the Turkish Parliament has not yet finished drafting the country’s new constitution.

The current constitution of the Turkish Republic, the 1982 Constitution, came into force as a direct result of the 1980 military coup. Additionally, the Constitution is notoriously authoritarian in its substance. Thus, its reform has been on Turkey’s political agenda since the late 1990s. The EU has played a major reform facilitator role by demanding specific constitutional reforms as a part of Turkey’s accession framework to the EU. Primarily in response to EU’s demands, the Parliament has amended the Constitution hundred and three times so far. Nevertheless, an entirely new constitution drafted by civilians was still considered necessary for Turkey to fully recover from the stigma of the coup and the authoritarianism it injected to the country’s governance.

In particular, the Prime Minister and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) built their campaign for the 2011 political elections almost entirely on the promise of a new constitution. The specific constitutional changes that the AKP wants to implement are yet to be revealed, apart from the party’s goal to replace the current parliamentary democracy with a semi-presidential regime.

The governing party’s preference for the semi-presidential regime stems from an anomaly in Turkey’s parliamentary democracy: a publicly elected president who enjoys only symbolic powers. Originally, the Constitution had foreseen that the president should be elected by Parliament as is usual in parliamentary democracies. But Parliament amended the election procedure in 2007 after non-majoritarian institutions – the Constitutional Court and the military – meddled in the election of Abdullah Gül, the current president. The Prime Minister and his party want to see this anomaly corrected with constitutional amendments extending the publicly elected president’s executive powers. Ideally, this should be done before the 2014 presidential elections, presumably to allow the Prime Minister to run for the office. Hence, his disappointment with the slow progress in the drafting of the new constitution.

Turkey’s ‘constitutional moment’

Turkey’s current constitutional reform process represents a unique ‘constitutional moment’ in the Republic’s history in which civilian democratic institutions draft a constitution without military interference. Thus, the reform process has the potential of serving greater purposes than the political ambitions of the Prime Minister and his party. Most crucially, the reform process could contribute towards the bridging of gaps between Turkish society’s increasingly polarised clusters, including the Kurdish and Turkish nationalists, conservative Kemalists, political Islamists and religious and cultural minorities. A meaningful constitutional debate could reveal different clusters’ similar as well as different expectations from the country’s governance. This would contribute to the diminishing, if not the demise, of long-standing mutual prejudices.

The constitutional reform process will also have profound effects on Turkey’s stance in Europe and the wider world: if successful, the reform process could reverse the European Commission’s increasingly sceptical evaluation of democracy in Turkey, thus, contributing towards a new high point in Turkey–EU relations. On the other hand, the Turkish government’s ambitions to lead the democratic reform processes in its region after the Arab Spring are well known. Setting an example for democratic constitution-making would provide the government with a legitimate claim for such leadership. The adoption process of Egypt’s new constitution demonstrates that the region is indeed in need of such a leader.

Shortcomings of the on-going reform process

Constitutions are highly entrenched laws that express ‘the common identity of the nation’. Thus, their adoption process requires substantial public involvement so that they would enjoy greater legitimacy than do regular pieces of legislation. In the Turkish case, the details of the reform process have not been fully discussed in public.

After the 2011 political elections a conciliatory committee was formed between the four political parties represented in the Parliament to work on constitutional reform (source in Turkish). The committee decided upfront to draft an entirely new constitution rather than limiting itself to the substance of the 1982 Constitution. Initially, the commission’s decision was met with celebration and raised expectations for a new constitution improving democracy in the country’s governance. However, the experiences during the committee’s first fifteen months of work raise doubts as to whether the reform process will live up to those expectations.

The Turkish electoral system involves an unusually high 10 per cent national electoral threshold that prevents optimal representation of different societal clusters. This reduces the reform process’ legitimacy, since the Parliament represents the public only partially. Before the 2011 elections, opposition parties as well as constitutional law scholars suggested reforms to be adopted to reduce the national election hurdle. The AKP, nevertheless, rejected those suggestions relying on the argument of stability in governance.

The Turkish criminal regime imposes various limitations on the freedoms of thought, speech and assembly. This prevents emergence of a liberal discourse where the public can discuss the country’s more contentious problems – such as the Kurdish issue, secularism, religious rights and minority and cultural rights – without the fear of being subject to criminal investigations. In order to encourage submission of opinions by civil society, organisations and individuals, the conciliatory committee does not disclose the opinions it received to the public. This secrecy not only prevents a substantial constitutional debate but it also stands as proof for the gravity of limitations on fundamental rights and freedoms.

The government deals with some constitutional matters as matters of daily politics without the involvement of the Parliament or the conciliatory committee. The government have recently re-launched peace talks with the Kurdish PKK. Any effort for the resolution of the country’s long-standing Kurdish issue deserves celebration. Nevertheless, the Kurdish issue does not only have a terror dimension, but it is inextricably linked to the poor accommodation of the Kurds’ as well as other minorities’ linguistic and cultural rights. Thus, it is difficult to envisage a stable solution to the Kurdish issue without a meaningful debate on the constitutional accommodation of minority and cultural rights in general.

Finally, an increasingly hostile political environment has overshadowed the reform process. Divergences between different political parties have become increasingly prevalent after the emergence of a parliamentary crisis involving imprisoned politicians shortly after the 2011 elections. Not only have terror and violence in the southeast as well as hate crimes in general shown an upward swing, but even the country’s scientific community seems dangerously politically polarised: after the brutal police suppression of wide-spread student protests of Erdoğan’s visit to the Middle East Technical University (METU) in Ankara, Turkish universities published opinions split between METU and its students and Erdoğan and, implicitly, the police forces.

The strict deadline imposed on the reform process by Erdoğan and the AKP exacerbates the hostilities. In the shadow of the deadline, a meaningful debate on the country’s long-standing problems with the potential of achieving consensus seems highly unrealistic. Different political groups see the reform of process as a now or never opportunity to push their individual agendas or to prevent the adoption of reforms they object. As a result, individual divergences rather than issues and alternative solutions to them dominate the constitutional reform debates.

The future of constitutional reform: the need for a ‘constitutional process’

Turkey’s on-going constitutional reform process is unique in the history of the Turkish Republic. For the first time civilian institutions alone are drafting the country’s constitution.

The reform process ought to serve greater purposes than the government AKP’s goal of establishing a semi-presidential regime before the 2014 presidential elections. Most crucially, the reform process could serve as a platform for an extensive public debate on the country’s long-standing and contentious problems.

Alas, the initial experiences imply that Turkey might be missing this historic opportunity. In addition to various factors that prevent the emergence of a constitutional debate, the impossible deadline imposed on the process exacerbates the already dangerous polarisation in Turkish society. Experiences of constitution-making in polarised societies, such as Israel, India, Ireland and South Africa, show that is vital to keep the reform process open-ended in order to design a democratic constitution filtered through all inclusive debates on the specific issues facing the society. South Africa’s search for a non-discriminatory constitution took eight years of phased negotiations during which the country was governed with an interim constitution. Notwithstanding Erdoğan’s disappointment, drafting a contemporary democratic constitution in fifteen months would be unprecedented.

The AKP’s insistence on the semi-presidential regime also implies that Turkey might be replacing one authoritarian constitution with another one: establishing stronger executives is the common feature of authoritarian constitutions. This is all the more worrisome, as it is not difficult to imagine that once the new constitution is adopted Erdoğan and the AKP will strongly oppose any further proposals for its amendment arguing that it is the first constitution in the Turkish Republic’s history adopted by civilians alone; thus, it should stay as it is.

In light of all this, the Prime Minister his party and other political groups need to stop treating the reform process as a now or never opportunity, a single ‘moment’ to push their own political agendas. They need to start attaching the salience to the reform process that it deserves.

Limitations on the freedoms of thought, expression and assembly should be lifted to engender a public debate on the country’s governance; and no strict deadline should be imposed on this debate. The Turkish political establishment owes this to the entire nation as well as future generations, whose identity will be defined by the new constitution.