ISTANBUL — That museum-schooled “look, don’t touch” detachment from the artifacts of history won’t get you anywhere in a place like Istanbul, an intricate, crafted quilt of multilayered pasts and a thronging, multicultural present.

The philosophy can’t help but be a little different here. The Turks know what the Romans know and what the citizens of any of the world’s ancient cities have long since figured out: Archaeology is everywhere, folks. Respect for the past can’t be allowed to get in the way of the working metropolis.

Istanbul is, indeed, the “Please Touch Museum” of archaeology.

My own introduction to this mind-set came as soon as we checked into our hotel. The Eresin Crown Hotel is an obscenely luxurious modern establishment located smack in the middle of the historic heart of Istanbul — in fact, on the very site of the Byzantine emperors’ Imperial Palace.

Like every other project in Istanbul, down to the most humble sewer repair, the Eresin Crown’s construction in the 1990s doubled as a serious archaeological dig. The results are on display for you to see. Many pieces of ancient Byzantium are behind glass in stately looking cases as you would expect, but many others simply stand around the main lobby and the ground-floor bar. I walked over and placed my hand on a sixth-century marble column, tracing my fingers over a low-relief cherub sculpted there millennia ago by some Greek artisan employed by a Caesar.

History in my hands. My Midwest museum-patron mind reeled.

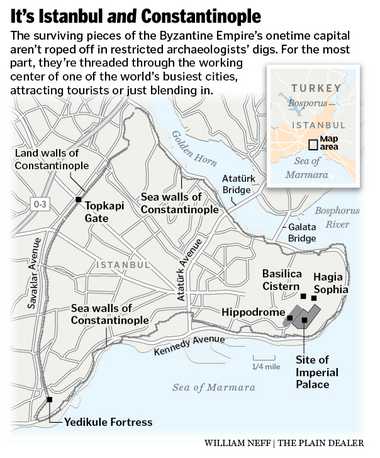

Some days later, my daughter and I ventured out to the ancient land walls of Constantinople, breached by the Ottoman Turks in 1453 at one of history’s most fateful turning points. Destroyed and rebuilt at intervals over the centuries since, the walls are still there to see; the workaday Turks don’t take much notice of them. And indeed, our Istanbul-native guide had some difficulty figuring out how to even access them from the roaring superhighways that now crisscross the walls and trace their 1,600-year-old course.

As a first taste, we explored what remains of the Yedikule Fortress, a seven-towered medieval bastion anchoring the southern junction of ancient Constantinople’s land and sea walls in what is now the working-class Fatih neighborhood of Istanbul.

Built up over the centuries, this fortress marks the site of what was once the principal ceremonial entrance to the Byzantine Imperial City.

We decided to scale the parapets of one of the towers added a bit later by Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II in the 15th century.

That’s right. My teenage daughter and I took to the steep, centuries-old masonry steps and went to the rooftops.

This is technically a state-run museum, and there were a couple of sleepy attendants in a booth somewhere, but what we chose to do inside this otherwise deserted Byzantine-Ottoman fortress was no concern of theirs.

At the summit of the tower, I immediately made my way to one of the battlements and caught my breath at the astonishing view across the sprawling Istanbul skyline and the Sea of Marmara spread out before me.

My hand came to rest on the corner of one of the crenellations piercing the battlement wall. To my horror, the entire heavy block of centuries-old masonry shifted beneath my arm.

I peered down at the grassy area six or seven stories below me and noticed more than a few similar pieces of dislocated Ottoman-period masonry half buried there. One easy shove was all it would take — I would leave off studying the processes of history and, instead, for what would surely be one of the only times in my life, participate in them.

I carefully replaced the chunk of masonry and made sure it was secure.

History might lie in my hands, but after all, it was the respect and admiration for it that had brought me halfway around the world to the parapets of the Yedikule Fortress in the first place.

We resumed our survey of the fortress and the rest of the Walls of Constantinople, using, as our principal tools, our eyes — and of course our imaginations.

via Hands-off style of exploring Istanbul is ancient history (gallery) | cleveland.com.