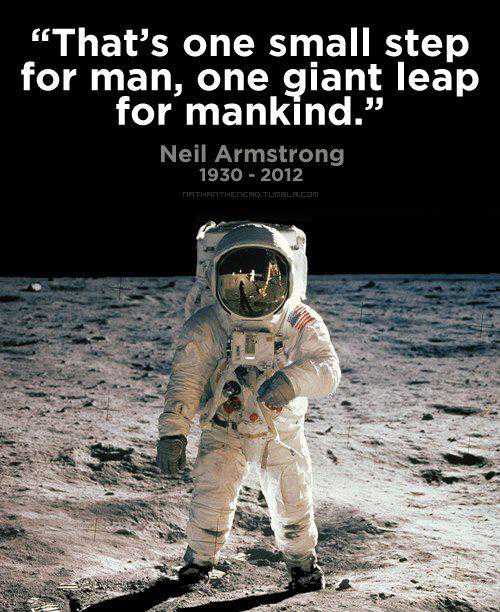

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an American astronaut, test pilot, aerospace engineer, university professor and United States Naval Aviator. He was the first person to walk on the Moon. Before becoming an astronaut, Armstrong was a United States Navy officer and had served in the Korean War. After the war, he served as a test pilot at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics High-Speed Flight Station, now known as the Dryden Flight Research Center, where he logged over 900 flights. He graduated from Purdue University and the University of Southern California.

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an American astronaut, test pilot, aerospace engineer, university professor and United States Naval Aviator. He was the first person to walk on the Moon. Before becoming an astronaut, Armstrong was a United States Navy officer and had served in the Korean War. After the war, he served as a test pilot at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics High-Speed Flight Station, now known as the Dryden Flight Research Center, where he logged over 900 flights. He graduated from Purdue University and the University of Southern California.

A participant in the U.S. Air Force’s Man In Space Soonest and X-20 Dyna-Soar human spaceflight programs, Armstrong joined the NASA Astronaut Corps in 1962. His first spaceflight was the NASA Gemini 8 mission in 1966, for which he was the command pilot, becoming one of the first U.S. civilians in space.[1] On this mission, he performed the first manned docking of two spacecraft with pilot David Scott.

Armstrong’s second and last spaceflight was as mission commander of the Apollo 11 moon landing in July 1969. On this mission, Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin descended to the lunar surface and spent 2½ hours exploring, while Michael Collins remained in orbit in the Command Module. Armstrong was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Richard Nixon along with Collins and Aldrin, the Congressional Space Medal of Honor by President Jimmy Carter in 1978, and the Congressional Gold Medal in 2009.

On August 25, 2012, Armstrong died in Cincinnati, Ohio,[2] at the age of 82 due to complications from blocked coronary arteries.

Contents

|

Early years

Armstrong was born on August 5, 1930,[3] in Wapakoneta, Ohio, to Stephen Koenig Armstrong and Viola Louise Engel.[4][5] He was of Scottish and German descent, and had two younger siblings, June and Dean. Stephen Armstrong worked as an auditor[6] for the Ohio state government, and the family moved around the state repeatedly in the 15 years following Armstrong’s birth, living in 20 different towns. His love for flying grew during this time, having gotten off to an early start when his father took 2-year-old Neil to the Cleveland Air Races. On July 20, 1936, when he was 6, he experienced his first airplane flight in Warren, Ohio, when he and his father took a ride in a Ford Trimotor, also known as the “Tin Goose”.[7]

His father’s last move was to Wapakoneta (Auglaize County) in 1944, where Neil attended Blume High School. Armstrong began taking flying lessons at the county airport, and was just 15 when he earned his flight certificate, before he had a driver’s license. Armstrong was active in the Boy Scouts and he eventually earned the rank of Eagle Scout. As an adult, he was recognized by the Boy Scouts of America with its Distinguished Eagle Scout Award and Silver Buffalo Award.[8] On July 18, 1969, while flying towards the Moon inside the Columbia, he greeted the Scouts: “I’d like to say hello to all my fellow Scouts and Scouters at Farragut State Park in Idaho having a National Jamboree there this week; and Apollo 11 would like to send them best wishes”. Houston: “Thank you, Apollo 11. I’m sure that, if they didn’t hear that, they’ll get the word through the news. Certainly appreciate that.”[9]

In 1947, Armstrong began studying aerospace engineering at Purdue University, where he was a member of Phi Delta Theta[10] and Kappa Kappa Psi.[11] He was only the second person in his family to attend college, and was also accepted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), but the only engineer he knew (who had attended MIT) dissuaded him from attending, telling Armstrong that it was not necessary to go all the way to Cambridge, Massachusetts, for a good education.[12] His college tuition was paid for under the Holloway Plan – successful applicants committed to two years of study, followed by three years of service in the United States Navy, then completion of the final two years of the degree. At Purdue, he earned average marks in his subjects, with a GPA that rose and fell during eight semesters. He was awarded a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from Purdue University in 1955, and, from the University of Southern California in 1970, a Master of Science degree in aerospace engineering.[3] Armstrong held honorary doctorates from a number of universities.[13]

Navy service

Armstrong’s call-up from the Navy arrived on January 26, 1949, requiring him to report to Naval Air Station Pensacola for flight training. This lasted almost 18 months, during which he qualified for carrier landing aboard the USS Cabot and USS Wright. On August 16, 1950, two weeks after his 20th birthday, Armstrong was informed by letter he was a fully qualified Naval Aviator.[14]

His first assignment was to Fleet Aircraft Service Squadron 7 at NAS San Diego (now known as NAS North Island). Two months later he was assigned to Fighter Squadron 51 (VF-51), an all-jet squadron, and made his first flight in a jet, an F9F-2B Panther, on January 5, 1951. In June, he made his first jet carrier landing on the USS Essex and was promoted the same week from Midshipman to Ensign. By the end of the month, the Essex had set sail with VF-51 aboard, bound for Korea, where they would act as ground-attack aircraft.[15]

Armstrong first saw action in the Korean War on August 29, 1951, as an escort for a photo reconnaissance plane over Songjin.[16] On September 3, 1951, Armstrong flew armed reconnaissance over the primary transportation and storage facilities south of the village of Majon-ni, west of Wonsan; while he was making a low bombing run at about 350 mph (560 km/h), Armstrong’s F9F Panther was hit by anti-aircraft fire. While trying to regain control, Armstrong collided with a pole at a height of about 20 feet (6.1 m), which sliced off an estimated three feet of the Panther’s right wing.[17]

Armstrong was able to fly the plane back to friendly territory, but due to the loss of the aileron, ejection was his only safe option. He planned to eject over water and await rescue by Navy helicopters, and therefore flew to an airfield near Pohang, but his ejection seat was blown back over land.[18] A jeep driven by a room-mate from flight school picked Armstrong up; it is unknown what happened to the wreckage of No. 125122 F9F-2.[19]

Armstrong flew 78 missions over Korea for a total of 121 hours in the air, most of which were in January 1952. He received the Air Medal for 20 combat missions, a Gold Star for the next 20, and the Korean Service Medal and Engagement Star.[20] Armstrong left the Navy at the age of 22 on August 23, 1952, and became a Lieutenant, Junior Grade in the United States Naval Reserve. He resigned his commission in the Naval Reserve on October 21, 1960.[21]

As a research pilot, Armstrong served as project pilot on the F-100 Super Sabre A and C variants, F-101 Voodoo, and the Lockheed F-104A Starfighter. He also flew the Bell X-1B, Bell X-5, North American X-15, F-105 Thunderchief, F-106 Delta Dart, B-47 Stratojet, KC-135 Stratotanker, and was one of eight elite pilots involved in the paraglider research vehicle program (Paresev).

College years

After his service with the Navy, Armstrong returned to Purdue, where his best grades came in the four semesters following his return from Korea. His final GPA was 4.8 out of 6.0.[22] He pledged the Phi Delta Theta fraternity after his return and he wrote and co-directed its musical as part of the all-student revue; he was also a member of Kappa Kappa Psi National Honorary Band Fraternity and a baritone player in the Purdue All-American Marching Band. Armstrong graduated in 1955 with a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering.[21]

While at Purdue, he met Janet Elizabeth Shearon, who was majoring in home economics. According to the two, there was no real courtship, and neither could remember the exact circumstances of their engagement, except that it occurred while Armstrong was working at the NACA’s Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. They were married on January 28, 1956, at the Congregational Church in Wilmette, Illinois. When he moved to Edwards Air Force Base, he lived in the bachelor quarters of the base, while Janet lived in the Westwood district of Los Angeles. After one semester, they moved into a house in Antelope Valley. Janet never finished her degree, a fact she regretted later in life.[23]

The couple had three children together: Eric, Karen, and Mark.[24] In June 1961, Karen was diagnosed with a malignant tumor of the middle part of her brain stem; X-ray treatment slowed its growth but her health deteriorated to the point where she could no longer walk or talk. Karen died of pneumonia, related to her weakened health, on January 28, 1962.[25]

Armstrong later completed his master of science degree in aeronautical engineering at the University of Southern California.[3]

Test pilot

A portrait of Armstrong taken November 20, 1956, while he was a test pilot at the NACA High-Speed Flight Station at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

Following his graduation from Purdue, Armstrong decided to become an experimental research test pilot. He applied at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics High-Speed Flight Station at Edwards Air Force Base; although they had no open positions, they did forward his application to the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio, where Armstrong began working at Lewis Field in March 1955.[26] Armstrong’s stint at Cleveland lasted a couple of months, and by July 1955, he had returned to Edwards AFB for his new job.[27]

On his first day at Edwards, Armstrong was tasked his first assignments, which were to pilot chase planes during releases of experimental aircraft from modified bombers. He also flew the modified bombers, and on one of these missions had his first flight incident at Edwards. Armstrong was in the right-hand seat of a Boeing B-29 Superfortress on March 22, 1956,[28] which was to air-drop a Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket. Armstrong sat the right-hand seat pilot while the left-hand seat commander, Stan Butchart, flew the B-29.[29]

As they ascended to 30,000 feet (9.1 km), the number four engine stopped and the propeller began windmilling (rotating freely) in the airstream. Hitting the switch that would stop the propeller’s spinning, Butchart found the propeller slowed but then started spinning again, this time even faster than the other engines; if it spun too fast, it would break apart. Their aircraft needed to hold an airspeed of 210 mph (338 km/h) to launch its Skyrocket payload, and the B-29 could not land with the Skyrocket still attached to its belly. Armstrong and Butchart brought the aircraft into a nose-down alignment to increase speed, then launched the Skyrocket. At the instant of launch, the number-four engine propeller disintegrated. Pieces of it damaged the number-three engine and hit the number-two engine. Butchart and Armstrong were forced to shut down the number-three engine, due to damage, and the number-one engine, due to the torque it created. They made a slow, circling descent from 30,000 ft (9,000 m) using only the number-two engine, and landed safely.[30]

Armstrong’s first flight in a rocket plane was on August 15, 1957, in the Bell X-1B, to an altitude of 11.4 miles (18.3 km). The nose landing gear broke on landing, which had happened on about a dozen previous flights of the Bell X-1B due to the aircraft’s design.[31] He later flew the North American X-15; Armstrong would fly the aircraft seven times before September 1962, and during his penultimate X-15 flight, he reached an altitude of 207,500 feet (63.2 km).[31]

Armstrong was involved in several incidents that went down in Edwards folklore and/or were chronicled in the memoirs of colleagues. The first was an X-15 flight on April 20, 1962, when Armstrong tested a self-adjusting control system. He flew to a height of 207,000 feet (63 km), (the highest he flew before Gemini 8), but he held the aircraft nose up too long during descent, and the X-15 bounced off the atmosphere back up to 140,000 ft (43 km). At that altitude, the atmosphere is so thin that aerodynamic surfaces have almost no effect. He flew past the landing field at Mach 3 (2,000 mph, or 3,200 km/h), over 100,000 feet (30 km) altitude, and ended up 40 miles (64 km) south of Edwards (legend has it that he flew as far as the Rose Bowl). After sufficient descent, he turned back toward the landing area, and barely managed to land without striking Joshua trees at the south end. It was the longest X-15 flight in both time and distance of the ground track.[32]

Four days later, Armstrong was involved in a second incident, when he flew for the only time with Chuck Yeager. Their job, flying a Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star, was to evaluate Smith Ranch Dry Lake for use as an emergency landing site for the X-15. In his autobiography, Yeager wrote that he knew the lake bed was unsuitable for landings after recent rains, but Armstrong insisted on flying out anyway. As they attempted a touch-and-go, the wheels became stuck and they had to wait for rescue. Armstrong tells a different version of events, where Yeager never tried to talk him out of it and they made a first successful landing on the east side of the lake. Then Yeager told him to try again, this time a bit slower. On the second landing, they became stuck and according to Armstrong, Yeager was in fits of laughter.[33]

Armstrong, 29, and X-15 #1 after a research flight in 1960.

Many of the test pilots at Edwards praised Armstrong’s engineering ability. Milt Thompson said he was “the most technically capable of the early X-15 pilots.” Bill Dana said Armstrong “had a mind that absorbed things like a sponge.” Those who flew for the Air Force tended to have a different opinion, especially people like Chuck Yeager and Pete Knight who did not have engineering degrees. Knight said that pilot-engineers flew in a way that was “more mechanical than it is flying,” and gave this as the reason why some pilot-engineers got into trouble: their flying skills did not come naturally.[34]

On May 21, 1962, Armstrong was involved in what Edwards’ folklore called the “Nellis Affair”. He was sent in an Lockheed F-104 Starfighter to inspect Delamar Dry Lake, again for emergency landings. He misjudged his altitude, and also did not realize that the landing gear had not fully extended. As he touched down, the landing gear began to retract. Armstrong applied full power to abort the landing, but the ventral fin and landing gear door struck the ground, damaging the radio and releasing hydraulic fluid. Without radio communication, Armstrong flew to Nellis Air Force Base, past the control tower, and waggled his wings, the signal for a no-radio approach. The loss of hydraulic fluid caused the tail-hook to release, and upon landing, he caught the arresting wire attached to an anchor chain, and dragged the chain along the runway.[35]

It took thirty minutes to clear the runway and rig an arresting cable. Armstrong telephoned Edwards and asked for someone to collect him. Milt Thompson was sent in an F-104B, the only two-seater available, but a plane Thompson had never flown. With great difficulty, Thompson made it to Nellis, but a strong crosswind caused a hard landing and the left main tire suffered a blowout. The runway was again closed to clear it, and Bill Dana was sent to Nellis in a T-33 Shooting Star, but he almost landed long — and the Nellis base operations office decided that to avoid any further problems, it would be best to find the three NASA pilots ground transport back to Edwards.[36]

Armstrong made seven flights in the X-15. He reached a top altitude of 207,500 feet (63.2 km) in the X-15-3,[37] and a top speed of Mach 5.74 (4,000 mph or 6,615 km/h) in the X-15-1; he left the Dryden Flight Research Center with a total of 2,400 flying hours.[38] Over his career, he flew more than 200 different models of aircraft.[3]

Astronaut career

Armstrong in an early Gemini spacesuit

There was no defining moment in Armstrong’s decision to become an astronaut. In 1958, he was selected for the U.S. Air Force’s Man In Space Soonest program. In November 1960, Armstrong was chosen as part of the pilot consultant group for the Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar, a military space plane; and on March 15, 1962, he was named as one of six pilot-engineers who would fly the space plane when it got off the design board.[39]

In the months after the announcement that applications were being sought for the second group of NASA astronauts, Armstrong became more and more excited about the prospects both of the Apollo program and of investigating a new aeronautical environment. Armstrong’s astronaut application had arrived about a week past the June 1, 1962 deadline, but Dick Day, with whom Armstrong had worked closely at Edwards, worked at the Manned Spacecraft Center, saw the late arrival of the application, and slipped it into the pile before anyone noticed.[40] At Brooks City-Base at the end of June, Armstrong underwent a medical exam that many of the applicants described as painful and at times seemingly pointless.[41]

Deke Slayton called Armstrong on September 13, 1962 and asked whether he would be interested in joining the NASA Astronaut Corps as part of what the press dubbed “the New Nine”; without hesitation, Armstrong said yes. The selections were kept secret until three days later, although newspaper reports had been circulating since earlier that year that he would be selected as the “first civilian astronaut”.[42] Armstrong was one of two civilian pilots selected for the second group, the other being Elliot See who, like Armstrong, was a Naval Aviator.[1] Armstrong did not become the first civilian to fly in space, as the Russians had launched Vostok 6 on June 16, 1963 with Valentina Tereshkova, a textile worker and amateur parachutist, aboard.[43]

Gemini program

Gemini 8

Armstrong goes through suiting up operations.

The crew assignments for Gemini 8 were announced on September 20, 1965, with Armstrong as Command Pilot and David Scott as Pilot. Scott was the first member of the third group of astronauts to receive a prime crew assignment. The mission launched on March 16, 1966; it was to be the most complex yet, with a rendezvous and docking with the unmanned Agena target vehicle, the second American extra-vehicular activity by Scott. In total the mission was planned to last 75 hours and 55 orbits. After the Agena lifted off at 10 am EST, the Titan II carrying Armstrong and Scott ignited at 11:41:02 am EST, putting them into an orbit from where they would chase the Agena.[44]

Recovery of the Gemini 8 spacecraft from the western Pacific Ocean

The rendezvous and first ever docking between two spacecraft was successfully completed after 6.5 hours in orbit.[45] Contact with the crew was intermittent due to the lack of tracking stations covering their entire orbits. Out of contact with the ground, the docked spacecraft began to roll, and Armstrong attempted to correct this with the Orbital Attitude and Maneuvering System (OAMS) of the Gemini spacecraft. Following the earlier advice of Mission Control, they undocked, but found that the roll increased dramatically to the point where they were turning about once per second, which meant the problem was in their Gemini’s attitude control. Armstrong decided the only course of action was to engage the Reentry Control System (RCS) and turn off the OAMS. Mission rules dictated that once this system was turned on, the spacecraft would have to reenter at the next possible opportunity. It was later thought that damaged wiring made one of the thrusters become stuck in the on position.[46]

Throughout the astronaut office there were a few people, most notably Walter Cunningham, who publicly stated that Armstrong and Scott had ignored the malfunction procedures for such an incident, and that Armstrong could have salvaged the mission if he had turned on only one of the two RCS rings, saving the other for mission objectives. These criticisms were unfounded; no malfunction procedures were written and it was possible to turn on only both RCS rings, not just one or the other. Gene Kranz wrote, “the crew reacted as they were trained, and they reacted wrong because we trained them wrong.” The mission planners and controllers had failed to realize that when two spacecraft are docked together, they must be considered to be one spacecraft.[47]

Armstrong himself was depressed[48] that the mission had been cut short, which cancelled most mission objectives and robbed Scott of his EVA.

Gemini 11

The last crew assignment for Armstrong during the Gemini program was as backup Command Pilot for Gemini 11, announced two days after the landing of Gemini 8. Having already trained for two flights, Armstrong was quite knowledgeable about the systems and was more in a teaching role[49] for the rookie backup Pilot, William Anders. The launch was on September 12, 1966[50] with Pete Conrad and Dick Gordon on board, who successfully completed the mission objectives, while Armstrong served as CAPCOM.

Following the flight, President Lyndon B. Johnson asked Armstrong and his wife to take part in a 24-day goodwill tour of South America.[51] Also on the tour, which took in 11 countries and 14 major cities, were Dick Gordon, George Low, their wives, and other government officials. In Paraguay, Armstrong impressed dignitaries by greeting them in their local language, Guarani;[52] in Brazil he talked about the exploits of the Brazilian-born Alberto Santos-Dumont, who was regarded as having beaten the Wright brothers with the first flying machine with his 14-bis.[53]

Apollo program

On January 27, 1967, the date of the Apollo 1 fire, Armstrong was in Washington, D.C., with Gordon Cooper, Dick Gordon, Jim Lovell and Scott Carpenter for the signing of the United Nations Outer Space Treaty. The astronauts chatted with the assembled dignitaries until 6:45 p.m. when Carpenter went to the airport, and the others returned to the Georgetown Inn, where they each found messages to phone the Manned Spacecraft Center. During these telephone calls they learned of the deaths of Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee. Armstrong and the group spent the rest of the night drinking scotch and discussing what had happened.[54]

On April 5, 1967, the same day the Apollo 1 investigation released its report on the fire, Armstrong assembled with 17 other astronauts for a meeting with Deke Slayton. The first thing Slayton said was, “The guys who are going to fly the first lunar missions are the guys in this room.”[55] According to Eugene Cernan, Armstrong showed no reaction to the statement. To Armstrong it came as no surprise – the room was full of veterans of Project Gemini, the only people who could fly the lunar missions. Slayton talked about the planned missions and named Armstrong to the backup crew for Apollo 9, which at that stage was planned to be a medium Earth orbit test of the Lunar Module-Command/Service Module combination. After design and manufacturing delays in the Lunar Module (LM), Apollo 9 and Apollo 8 swapped crews. Based on the normal crew rotation scheme, Armstrong would command Apollo 11.[56]

To attempt to give the astronauts experience with how the LM would fly on its final landing descent, NASA commissioned Bell Aircraft to build two Lunar Landing Research Vehicles, later augmented with three Lunar Landing Training Vehicles (LLTV). Nicknamed the “Flying Bedsteads”, they simulated the Moon’s one-sixth of Earth’s gravity by using a turbofan engine to support the remaining five-sixths of the craft’s weight. On May 6, 1968, about 100 feet (30 m) above the ground, Armstrong’s controls started to degrade and the LLTV began banking.[57] He ejected safely (later analysis suggested that if he had ejected 0.5 seconds later, his parachute would not have opened in time). His only injury was from biting his tongue. Even though he was nearly killed, Armstrong maintained that without the LLRV and LLTV, the lunar landings would not have been successful, as they gave commanders valuable experience in the behavior of lunar landing craft.[58]

Apollo 11

The Apollo 11 crew portrait. Left to right are Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin.

After Armstrong served as backup commander for Apollo 8, Slayton offered him the post of commander of Apollo 11 on December 23, 1968, as 8 orbited the Moon.[59] In a meeting that was not made public until the publication of Armstrong’s biography in 2005, Slayton told him that although the planned crew was Armstrong as commander, lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin and command module pilot Michael Collins, he was offering the chance to replace Aldrin with Jim Lovell. After thinking it over for a day, Armstrong told Slayton he would stick with Aldrin, as he had no difficulty working with him and thought Lovell deserved his own command. Replacing Aldrin with Lovell would have made Lovell the Lunar Module Pilot, unofficially the lowest ranked member, and Armstrong could not justify placing Lovell, the commander of Gemini 12, in the number 3 position of the crew.[60]

A March 1969 meeting between Slayton, George Low, Bob Gilruth, and Chris Kraft determined that Armstrong would be the first person on the Moon, in some part because NASA management saw Armstrong as a person who did not have a large ego.[61] A press conference held on April 14, 1969 gave the design of the LM cabin as the reason for Armstrong’s being first; the hatch opened inwards and to the right, making it difficult for the lunar module pilot, on the right-hand side, to egress first. Slayton added, “Secondly, just on a pure protocol basis, I figured the commander ought to be the first guy out. . . . I changed it as soon as I found they had the time line that showed that. Bob Gilruth approved my decision.”[62] At the time of their meeting, the four men did not know about the hatch issue. The first knowledge of the meeting outside the small group came when Kraft wrote his 2001 autobiography.[63]

On July 16, 1969, Armstrong received a crescent moon carved out of Styrofoam from the pad leader, Guenter Wendt, who described it as a key to the Moon. In return, Armstrong gave Wendt a ticket for a “space taxi” “good between two planets”.[64]

Voyage to the Moon

Aldrin took this picture of Armstrong in the cabin after the completion of the EVA.

During the Apollo 11 launch, Armstrong’s heart reached a top rate of 110 beats per minute.[65] He found the first stage to be the loudest – much noisier than the Gemini 8 Titan II launch – and the Apollo CSM was relatively roomy compared to the Gemini capsule. This ability to move around was suspected to be the cause of space sickness that had hit members of previous crews, but none of the Apollo 11 crew suffered from it; Armstrong was especially happy, as he had been prone to motion sickness as a child and could experience nausea after doing long periods of aerobatics.[66]

The objective of Apollo 11 was to land safely rather than to touch down with precision on a particular spot. Three minutes into the lunar descent burn, Armstrong noted that craters were passing about two seconds too early, which meant the Eagle would probably touch down beyond the planned landing zone by several miles.[67] As the Eagle’s landing radar acquired the surface, several computer error alarms appeared. The first was a code 1202 alarm, and even with their extensive training, neither Armstrong nor Aldrin was aware of what this code meant. They promptly received word from CAPCOM in Houston that the alarms were not a concern; the 1202 and 1201 alarms were caused by an executive overflow in the lunar module computer. As described by Buzz Aldrin in the documentary In the Shadow of the Moon, the overflow condition was caused by his own counter-checklist choice of leaving the docking radar on during the landing process, so the computer had to process unnecessary radar data and did not have enough time to execute all tasks, dropping lower-priority ones. Aldrin stated that he did so with the objective of facilitating re-docking with the CM should an abort become necessary, not realizing that it would cause the overflow condition.[citation needed]

When Armstrong noticed they were heading towards a landing area which he believed was unsafe, he took over manual control of the LM, and attempted to find an area which seemed safer, taking longer than expected, and longer than most simulations had taken.[68] For this reason, there was concern from mission control that the LM was running low on fuel.[69] Upon landing, Aldrin and Armstrong believed they had about 40 seconds worth of fuel left, including the 20 seconds worth of fuel which had to be saved in the event of an abort.[70] During training, Armstrong had landed the LLTV with less than 15 seconds left on several occasions, and he was also confident the LM could survive a straight-down fall from 50 feet (15 m) if needed. Analysis after the mission showed that at touchdown there were 45 to 50 seconds of propellant burn time left.[71]

The landing on the surface of the moon occurred at 20:17:39 UTC on July 20, 1969.[72] When a sensor attached to the legs of the still hovering Lunar Module made lunar contact, a panel light inside the LM lit up and Aldrin called out, “Contact light.” As the LM settled on the surface Aldrin then said, “Okay. Engine stop,” and Armstrong said, “Shutdown.” The first words Armstrong intentionally spoke to Mission Control and the world from the lunar surface were, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” Aldrin and Armstrong celebrated with a brisk handshake and pat on the back before quickly returning to the checklist of tasks needed to ready the lunar module for liftoff from the Moon should an emergency unfold during the first moments on the lunar surface.[73][74][75] During the critical landing, the only message from Houston was “30 seconds”, meaning the amount of fuel left. When Armstrong had confirmed touch-down, Houston expressed their worries during the manual landing as “You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again”.[70]

First Moon walk

|

“That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind”

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

Although the official NASA flight plan called for a crew rest period before extra-vehicular activity, Armstrong requested that the EVA be moved to earlier in the evening, Houston time. Once Armstrong and Aldrin were ready to go outside, Eagle was depressurized, the hatch was opened and Armstrong made his way down the ladder first.

Armstrong describes the lunar surface.

At the bottom of the ladder, Armstrong said “I’m going to step off the LEM now” (referring to the Apollo Lunar Module). He then turned and set his left boot on the surface at 2:56 UTC July 21, 1969,[76] then spoke the famous words “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”[77]

Armstrong had decided on this statement following a train of thought that he had had after launch and during the hours after landing.[78] The broadcast did not have the “a” before “man”, rendering the phrase a contradiction (as man in such use is synonymous with mankind). NASA and Armstrong insisted for years that static had obscured the “a”, with Armstrong stating he would never make such a mistake, but after repeated listenings to recordings, Armstrong admitted he must have dropped the “a”.[77] Armstrong later said he “would hope that history would grant me leeway for dropping the syllable and understand that it was certainly intended, even if it was not said – although it might actually have been”.[79]

Armstrong on the Moon

It has since been claimed that acoustic analysis of the recording reveals the presence of the missing “a”;[77][80] Peter Shann Ford, an Australia-based computer programmer, conducted a digital audio analysis and claims that Armstrong did, in fact, say “a man”, but the “a” was inaudible due to the limitations of communications technology of the time.[77][81][82] Ford and James R. Hansen, Armstrong’s authorized biographer, presented these findings to Armstrong and NASA representatives, who conducted their own analysis.[83] The article by Ford, however, is published on Ford’s own web site rather than in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, and linguists David Beaver and Mark Liberman wrote of their skepticism of Ford’s claims on the blog Language Log.[84] Although Armstrong found Ford’s analysis “persuasive”,[85] he expressed his preference that written quotations include the “a” in parentheses.[citation needed]

When Armstrong made his proclamation, Voice of America was rebroadcast live via the BBC and many other stations worldwide. The estimated global audience at that moment was 450 million listeners,[86] out of a then estimated world population of 3.631 billion people.[87]

Armstrong prepares to take the first step on the Moon.

About 20 minutes after the first step, Aldrin joined Armstrong on the surface and became the second human to set foot on the Moon, and the duo began their tasks of investigating how easily a person could operate on the lunar surface. Early on, they unveiled a plaque commemorating their flight, and also planted the flag of the United States. The flag used on this mission had a metal rod to hold it horizontal from its pole. Since the rod did not fully extend, and the flag was tightly folded and packed during the journey, the flag ended up with a slightly wavy appearance, as if there were a breeze.[88] Shortly after their flag planting, President Richard Nixon spoke to them by a telephone call from his office. The President spoke for about a minute, after which Armstrong responded for about thirty seconds.[89]

In the entire Apollo 11 photographic record, there are only five images of Armstrong partly shown or reflected. The mission was planned to the minute, with the majority of photographic tasks to be performed by Armstrong with a single Hasselblad camera.[90]

After helping to set up the Early Apollo Scientific Experiment Package, Armstrong went for a walk to what is now known as East Crater, 65 yards (59 m) east of the LM, the greatest distance traveled from the LM on the mission. Armstrong’s final task was to leave a small package of memorial items to deceased Soviet cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin and Vladimir Komarov, and Apollo 1 astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger B. Chaffee. The time spent on EVA during Apollo 11 was about two and a half hours, the shortest of any of the six Apollo lunar landing missions;[91] each of the subsequent five landings were allotted gradually longer periods for EVA activities – the crew of Apollo 17, by comparison, spent over 22 hours exploring the lunar surface.[91]

Return to Earth

The Apollo 11 crew and President Richard Nixon.

After they re-entered the LM, the hatch was closed and sealed. While preparing for the liftoff from the lunar surface, Armstrong and Aldrin discovered that, in their bulky spacesuits, they had broken the ignition switch for the ascent engine; using part of a pen, they pushed the circuit breaker in to activate the launch sequence.[92] Aldrin still possesses the pen which they used to do this. The lunar module then continued to its rendezvous and docked with Columbia, the command and service module. The three astronauts returned to Earth and splashed down in the Pacific ocean, to be picked up by the USS Hornet (CV-12).[93]

After being released from an 18-day quarantine to ensure that they had not picked up any infections or diseases from the Moon, the crew were feted across the United States and around the world as part of a 45-day “Giant Leap” tour. Armstrong then took part in Bob Hope’s 1969 USO show, primarily to Vietnam.[94]

In May 1970, Armstrong traveled to the Soviet Union to present a talk at the 13th annual conference of the International Committee on Space Research; after arriving in Leningrad from Poland, he traveled to Moscow where he met Premier Alexei Kosygin. He was the first westerner to see the supersonic Tupolev Tu-144 and was given a tour of the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center, which Armstrong described as “a bit Victorian in nature”.[95] At the end of the day, he was surprised to view delayed video of the launch of Soyuz 9 – it had not occurred to Armstrong that the mission was taking place, even though Valentina Tereshkova had been his host and her husband, Andriyan Nikolayev, was on board.[96]

Life after Apollo

Teaching

Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering at Purdue University

Armstrong announced shortly after the Apollo 11 flight that he did not plan to fly in space again.[97] He was appointed Deputy Associate Administrator for aeronautics for the Office of Advanced Research and Technology, Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), but served in this position for only a year, and resigned from it and NASA as a whole in 1971.[98]

He accepted a teaching position in the Department of Aerospace Engineering at the University of Cincinnati,[99] having decided on Cincinnati over other universities, including his alma mater, Purdue, because it had a small aerospace department; he hoped that the faculty members would not be annoyed that he came straight into a professorship with only the USC master’s degree.[100] He began the work while stationed at Edwards years before, and finally completed it after Apollo 11 by presenting a report on various aspects of Apollo, instead of a thesis on the simulation of hypersonic flight. The official job title he received at Cincinnati was University Professor of Aerospace Engineering. After teaching for eight years, he resigned in 1979 without explaining his reason for leaving.[101]

NASA accident investigations

Armstrong served on two spaceflight accident investigations. The first was in 1970, after Apollo 13, where as part of Edgar Cortwright’s panel, he produced a detailed chronology of the flight. Armstrong personally opposed the report’s recommendation to re-design the service module’s oxygen tanks, the source of the explosion.[102] In 1986, President Ronald Reagan appointed him to the Rogers Commission which investigated the Space-shuttle Challenger disaster of that year. As vice-chairman, Armstrong was in charge of the operational side of the commission.[103]

Business activities

After Armstrong retired from NASA in 1971, he avoided offers from businesses to act as a spokesman. The first company to successfully approach him was Chrysler, for whom he appeared in advertising starting in January 1979. Armstrong thought they had a strong engineering division, plus they were in financial difficulty. He acted as a spokesman for other companies, including General Time Corporation and the Bankers Association of America. He acted as a spokesman for US businesses only.[104]

Along with spokesman duties, he also served on the board of directors of several companies, including Marathon Oil, Learjet, Cinergy (Cincinnati Gas & Electric Company), Taft Broadcasting, United Airlines, Eaton Corporation, AIL Systems, and Thiokol.[105] He joined Thiokol’s board after he served on the Rogers Commission; the Space Shuttle Challenger was destroyed due to a problem with the Thiokol-manufactured solid rocket boosters. He retired as chairman of the board of EDO Corporation in 2002.[106]

Personal life

Neil Armstrong (second from right, middle row) visits with USAF members in Southwest Asia, 2010. To his left are Gene Cernan and Jim Lovell.

Armstrong was approached by political groups from both ends of the spectrum after his aeronautical career. Unlike former astronauts and United States Senators John Glenn and Harrison Schmitt, Armstrong declined all offers. Personally, he was in favor of states’ rights and against the United States acting as the “world’s policeman”.[107]

In the late 1950s, Armstrong applied at a local Methodist church to lead a Boy Scout troop. When asked for his religious affiliation, he labeled himself as a Deist.[108]

In 1972, Armstrong was welcomed into the town of Langholm, Scotland, the traditional seat of Clan Armstrong; he was made the first freeman of the burgh, and happily declared the town his home.[109] The Justice of the Peace read from an unrepealed 400-year-old law that required him to hang any Armstrong found in the town.[110]

In the fall of 1979, Armstrong was working at his farm near Lebanon, Ohio. As he jumped off of the back of his grain truck, his wedding ring caught in the wheel, tearing off the tip of his ring finger. He collected the severed digit and packed it in ice, and surgeons reattached it at the Jewish Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky.[111] In February 1991, he suffered a mild heart attack while skiing with friends at Aspen, Colorado[112] a year after his father had died, and nine months after the death of his mother.

Armstrong’s first wife, Janet, divorced him in 1994, after 38 years of marriage.[113] He had met his second wife, Carol Held Knight, in 1992 at a golf tournament, where they were seated together at the breakfast table. She said little to Armstrong, but two weeks later she received a call from him asking what she was doing—she replied she was cutting down a cherry tree; 35 minutes later Armstrong was at her house to help out. They were married on June 12, 1994, in Ohio, and then had a second ceremony, at San Ysidro Ranch, in California. He lived in Indian Hill, Ohio.[114]

Quincy Jones presents platinum copies of “Fly Me to the Moon” to Neil Armstrong (right) and former Senator John Glenn, September 24, 2008.

After 1994, Armstrong refused all requests for autographs because he found that his signed items were selling for large amounts of money and that many forgeries are in circulation; any requests sent to him received a form letter in reply saying that he has stopped signing. Although his no-autograph policy was well known, author Andrew Smith observed people at the 2002 Reno Air Races still trying to get signatures, with one person even claiming, “If you shove something close enough in front of his face, he’ll sign.”[115] He also stopped sending out congratulatory letters to new Eagle Scouts, because he believed these letters should come from people who know the Scouts personally.[116]

Use of Armstrong’s name, image, and famous quote caused him problems over the years. MTV wanted to use his quote for its now-famous ident depicting the Apollo 11 landing when it launched in 1981, but he declined.[117] Armstrong sued Hallmark Cards in 1994 after they used his name and a recording of “one small step” quote in a Christmas ornament without permission. The lawsuit was settled out of court[118] for an undisclosed amount of money which Armstrong donated to Purdue.[119]

In May 2005, Armstrong became involved in an unusual legal battle with his barber of 20 years, Marx Sizemore. After cutting Armstrong’s hair, Sizemore sold some of it to a collector for $3,000 without Armstrong’s knowledge or permission.[120] Armstrong threatened legal action unless the barber returned the hair or donated the proceeds to a charity of Armstrong’s choosing. Sizemore, unable to get the hair back, decided to donate the proceeds to the charity of Armstrong’s choice.[121]

Illness and death

Armstrong underwent surgery on August 7, 2012, to relieve blocked coronary arteries.[122] He died on August 25, in Cincinnati, Ohio,[2] following complications resulting from these cardiovascular procedures. Hours later, President Barack Obama released a statement on Armstrong’s death describing him as “among the greatest of American heroes – not just of his time, but of all time.”[123][124] According to a statement released by the White House, Obama added that he, along with the Apollo 11 crew, carried the aspirations of the United States’ citizens and that Armstrong had delivered “a moment of human achievement that will never be forgotten.”

Armstrong’s family also released a statement that read “[he was a] reluctant American hero [and had] served his nation proudly, as a navy fighter pilot, test pilot, and astronaut. While we mourn the loss of a very good man, we also celebrate his remarkable life and hope that it serves as an example to young people around the world to work hard to make their dreams come true, to be willing to explore and push the limits, and to selflessly serve a cause greater than themselves.”[125]

Armstrong’s colleague on the Apollo 11 mission, Buzz Aldrin, commented that he was “very saddened to learn of the passing. I know I am joined by millions of others in mourning the passing of a true American hero and the best pilot I ever knew.”[126][127] Command module pilot Michael Collins said simply, “He was the best, and I will miss him terribly.”[128] NASA Administrator Charles Bolden said that Armstrong will be “remembered for taking humankind’s first small step on a world beyond our own”.[129][130]

Armstrong’s family statement made the tribute “For those who may ask what they can do to honor Neil, we have a simple request. Honor his example of service, accomplishment and modesty, and the next time you walk outside on a clear night and see the moon smiling down at you, think of Neil Armstrong and give him a wink.”[125] This prompted many responses, including the Twitter hashtag “#WinkAtTheMoon”.[131]

Legacy

Armstrong and Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space, Soviet Union, 1970

Armstrong received many honors and awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Congressional Space Medal of Honor, the Robert H. Goddard Memorial Trophy, the Sylvanus Thayer Award, the Collier Trophy from the National Aeronautics Association, and the Congressional Gold Medal. The lunar crater Armstrong, 31 mi (50 km) from the Apollo 11 landing site, and asteroid 6469 Armstrong[132] are named in his honor. Armstrong was also inducted into the Aerospace Walk of Honor and the United States Astronaut Hall of Fame.[133][134] Armstrong and his Apollo 11 crewmates were the 1999 recipients of the Langley Gold Medal from the Smithsonian Institution.

Throughout the United States, there are more than a dozen elementary, middle and high schools named in his honor,[135] and many places around the world have streets, buildings, schools, and other places named for Armstrong and/or Apollo.[136] In 1969, folk songwriter and singer John Stewart recorded “Armstrong”, a tribute to Armstrong and his first steps on the moon. Purdue University announced in October 2004 that its new engineering building would be named Neil Armstrong Hall of Engineering in his honor;[137] the building cost $53.2 million and was dedicated on October 27, 2007, during a ceremony at which Armstrong was joined by fourteen other Purdue Astronauts.[138] In 1971, Armstrong was awarded the Sylvanus Thayer Award by the United States Military Academy at West Point for his service to the country.[139] The Neil Armstrong Air and Space Museum is located in his hometown of Wapakoneta, Ohio, although it has no official ties to Armstrong and the airport in New Knoxville where he took his first flying lessons is named for him.[140]

Michael Collins, President George W. Bush, Armstrong, and Aldrin during celebrations of the 35th anniversary of the Apollo 11 flight, July 21, 2004

Armstrong’s authorized biography, First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong, was published in 2005. For many years, Armstrong turned down biography offers from authors such as Stephen Ambrose and James A. Michener, but agreed to work with James R. Hansen after reading one of Hansen’s other biographies.[141]

In a 2010 Space Foundation survey, Armstrong was ranked as the #1 most popular space hero.[142]

The press often asked Armstrong for his views on the future of spaceflight. In 2005, Armstrong said that a manned mission to Mars will be easier than the lunar challenge of the 1960s: “I suspect that even though the various questions are difficult and many, they are not as difficult and many as those we faced when we started the Apollo [space program] in 1961.” In 2010, he made a rare public criticism of the decision to cancel the Ares 1 launch vehicle and the Constellation moon landing program.[143] In an open public letter also signed by Apollo veterans Jim Lovell and Gene Cernan, he noted, “For The United States, the leading space faring nation for nearly half a century, to be without carriage to low Earth orbit and with no human exploration capability to go beyond Earth orbit for an indeterminate time into the future, destines our nation to become one of second or even third rate stature”.[144] Armstrong had also publicly recalled his initial concerns about the Apollo 11 mission, when he had believed there was only a 50% chance of landing on the moon. “I was elated, ecstatic and extremely surprised that we were successful”, he later said.[145]

On November 18, 2010, at age eighty, Armstrong said in a speech during the Science & Technology Summit in The Hague, Netherlands, that he would offer his services as commander on a mission to Mars if he were asked.[146]

Leave a Reply