Russia and the west must use their leverage to bring about a ceasefire and halt Syria’s descent into full-scale civil

-

-

Jonathan Steele

- guardian.co.uk, Monday 9 July 2012 17.00 EDT

- Comments (…)

-

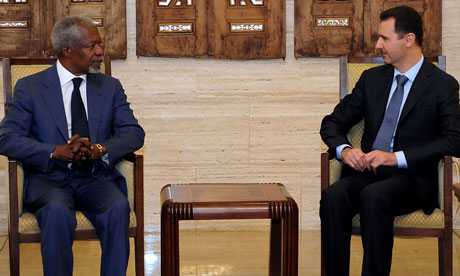

Kofi Annan in talks with Bashar al-Assad in Damascus on 9 July. ‘Annan needs maximum support in persuading the parties that compromise is more realistic than seeking victory.’ Photograph: Ho/AFP/Getty Images

With Syria sinking into full-scale civil war, Kofi Annan was right last week to call for an end to the “destructive competition” between security council members. Western powers’ efforts to shame and blame Russia for allegedly blocking political change are hypocritical when they support the accelerating flow of arms into the country, which only makes an eventual solution more costly in lives.

The past three months have seen a huge increase in clashes between armed rebels and government units as well as unremitting shelling of opposition strongholds by Bashar al-Assad’s forces. Tens of thousands of people have fled their homes. Hundreds of civilians have died as well as scores of soldiers and police. Government supporters are being assassinated. The conflict’s militarisation is bringing despair to many who came on to the streets last year to demonstrate for peaceful change. Syria’s identity as a place of religious tolerance and communal good-neighbourliness risks being shattered for ever as Salafi fundamentalists and al Qaida-style bombers join the fray.

In spite of mounting losses the government still believes it can win through superior force and the mass detention of activists. Its fallback is to hold out indefinitely in Damascus and Aleppo even if totally disarming the opposition proves impossible and other parts of the country are mired in perpetual insurgency. For its part the rebels also count on victory. They bank on a Libyan-style Nato onslaught of massive air strikes once the US presidential election has passed. The CIA is already engaged in southern Turkey in funnelling supplies to rebels, and the Turkish air force is gearing up for action.

Annan needs maximum support in persuading the parties that compromise is more realistic than seeking victory. His last-gasp talks with President Assad on Monday will be followed by meetings with the Syrian opposition. They will only bear fruit if world powers use their leverage on their friends to bring about a ceasefire and a political process that can lead to democratic reform.

The priority is an arms embargo. Russia should urge Assad to withdraw his heavy weaponry from cities and release detainees if the opposition also halts its attacks. Moscow must make it clear that Russian military supplies will cease if he does not comply. Iran should make similar commitments. In order to press the rebels to compromise, the west should publicly rule out military intervention under any circumstance and urge Qatar and Saudi Arabia to stop funding the arms race.

Calling on Assad to resign as a precondition for talks has failed. His term runs to 2014 and it would be better to use the intervening time to negotiate a government of national unity that can prepare for elections to a constituent assembly and make other reforms. Useful lessons can be drawn from Yemen, where a long-time ruler left office without outside military interference. Could Syria make a similar transition? It starts from a different place, alas. Some 265 civilians died at the hands of security forces in Yemen, far fewer than in Syria. Western states and the Arab League did not vilify Ali Abdullah Saleh by shouting that he had lost legitimacy. When he announced he would not seek re-election, it was less of a humiliation. An amnesty was given to him and his family, whereas Assad has been offered no such option.

Jamal Benomar, the UN secretary-general’s special adviser for Yemen, was a key player. A Moroccan with a distinguished history as a dissident in his own country but no high profile like Annan, he sees other differences with Syria. One was the right timing of sanctions.

“In Yemen the breakthrough came in October with a unanimous resolution of the security council,” Benomar told me recently in Sana’a. “I was asked to submit a report on implementation within 30 days. After investigating for two weeks I saw Saleh and told him my report was very negative. Voices in the security council were talking about sanctions.” Saleh saw the threat and agreed to enter negotiations with the opposition. In Syria sanctions were imposed very early and can no longer be a useful weapon.

Another difference is that neither the Yemeni opposition nor the government thought that they could win by force or through foreign military help. As Benomar recalls: “Saleh created a military committee and asked them if they could guarantee a military solution. They said that they couldn’t. At best 20% of the country would be controlled by the government, and 25% by the opposition, and the rest would face complete lawlessness. Saleh dismissed the group and appointed another one, but they produced the same answer. It was not worth pursuing a military solution, and the cost in lives would be extremely high.”

In Syria it will take a greater effort just to get negotiations started. Polarisation is extreme, and oppositionists who recommend talks are denounced as regime stooges. Nor is there any certainty that Assad’s side is ready for serious concessions. But intensifying the civil war is a far less responsible option.