By ADAM ENTOUS And JOE PARKINSON

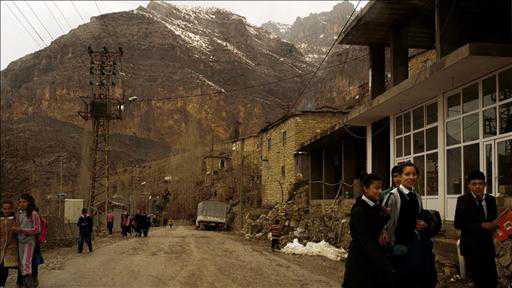

ULUDERE, Turkey—After winding along a narrow mountain ridge, a caravan of 38 men and mules paused on the Turkish-Iraqi border. Then they heard the propellers overhead. Minutes later, Turkish military aircraft dropped bombs that killed all but four of the men.

The strike in late December was meant to knock out Kurdish separatist fighters. Instead it killed civilians smuggling gasoline, a tragic blunder in Turkey’s nearly three-decade campaign against the guerrillas. The killings ignited protests across the country and prompted wide-ranging official inquiries.

The civilian toll also set off alarms at the Pentagon: It was a U.S. Predator drone that spotted the men and pack animals, officials said, and American officers alerted Turkey.

A Turkish strike to knock out Kurdish separatist fighters instead killed civilians smuggling gasoline. The blunder has been linked to intelligence from U.S. drones in the region and raised questions about their value. WSJ’s Joe Parkinson reports. Photo: WSJ

The U.S. drone flew away after reporting the caravan’s movements, leaving the Turkish military to decide whether to attack, according to an internal assessment by the U.S. Defense Department, described to The Wall Street Journal. “The Turks made the call,” a senior U.S. defense official said. “It wasn’t an American decision.”

The U.S. role, which hasn’t previously been reported, revealed the risks in a new strategy for extending American influence around the globe. It raises an outstanding question for the White House and Congress: How far do we entrust allies with our deadly drone technology?

After a decade of troop-intensive land wars, the Obama administration is promoting advanced drones, elite special forces and intelligence resources as a more nimble, and less expensive, source of military power. The strategy relies heavily on close cooperation with regional allies, in part to reduce the need for American troops on the ground.

In Pakistan and Somalia, where local authorities can’t or won’t act against militants, the U.S. employs armed drones and special-operations teams to track and kill suspected terrorists. In Yemen, the U.S. carries out drone strikes with the government’s approval. In Turkey—a North Atlantic Treaty Organization member that has a modern air force—the U.S. helps provide intelligence for operations but plays no direct role in any strikes.

The downside to such arrangements, say current and former U.S. officials, is that countries can use U.S. intelligence in ways the Pentagon and the Central Intelligence Agency can’t control. Allies have varying standards for deciding who is a justified target. And these partnerships can embroil the U.S. in local disputes with only slender links to the security of Americans.

“What happens if this information gets to the [foreign] government and they do something wrong with it, or it gets into the hands of someone who does something wrong with it?” said Rep. Mike Rogers (R., Mich.), chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, who didn’t know specific details of the attack.

At the Pentagon, press secretary George Little said when asked about the strike, “Without commenting on matters of intelligence, the United States strongly values its enduring military relationship with Turkey.”

The conflict between Turkish security forces and the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, has taken an estimated 40,000 lives since violence first flared in the 1980s. Ethnic Kurds, about 18% of Turkey’s population, have long sought a degree of political autonomy and the right to public education in their native tongue. Tensions have risen since Turkey last fall intensified its campaign against the PKK, which the U.S. and European Union designate a terrorist group.

U.S. drone flights in support of Turkey date from November 2007, when the Bush administration set up what is called a Combined Intelligence Fusion Cell in Ankara, part of an effort to nurture ties with the government led by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. U.S. and Turkish officers sit side by side in the dimly lighted complex monitoring real-time video feeds from Predator drones.

The Obama administration has moved to expand cooperation—by stepping up intelligence sharing and by supporting Turkey’s request to buy armed and unarmed U.S. drones to give the Turks full control.

The issue is sensitive for both sides. Turkey doesn’t want to be seen as reliant on the U.S. And selling drones to Turkey faces opposition from key members of Congress, who worry about spreading the technology, as well as Turkey’s standards for deciding when to launch a strike.

While the White House is moving forward with plans to provide Italy with arms for its drones, proposals to sell or lease drones to Turkey face resistance in Congress, which reviews such sales in advance. Proponents argue they build long-term military relations with close allies, as well as give U.S. companies better access to the fast-growing global market.

The caravan strike is illustrative of the dangers. Servet Encu, 42 years old, said he had made the journey across the mountainous border separating Turkey and Iraq several times a month since he was a teenager, smuggling all kinds of goods.

In his and other impoverished Kurdish villages of southeastern Turkey, smuggling is a trade made profitable by differences between the two countries, including taxes and currency values. Fuel costs twice as much in Turkey as in Iraq, a substantial oil producer, rewarding smugglers who ferry jugs of gasoline through the mountains. The Turkish military usually doesn’t bother villagers crossing the border, as long as they aren’t smuggling weapons or drugs. But PKK militants also cross the border in the region.

The convoy, laden with food and gasoline, was returning to Turkey on Dec. 28. They were less than an hour from home after hiking along barren, icy ridges for more than four hours, Mr. Encu said in an interview.

Mr. Encu called his Kurdish village by cellphone for help picking a route to avoid Turkish soldiers who might confiscate their cargo, he recalled.

Above and out of sight, a U.S. Predator drone loitered. It was on a routine patrol when U.S. personnel monitoring its video feeds spotted the caravan just inside Iraq and moving toward the Turkish border, according to U.S. officials and the Pentagon’s assessment of the fatal strike.

U.S. military officers at the Fusion Cell in Ankara couldn’t tell whether the men, bundled in heavy jackets, were civilians or guerrilla fighters. But their location in an area frequented by guerrilla fighters raised suspicions. The Americans alerted their Turkish counterparts.

U.S. officials said additional surveillance from the Predator might have helped the Turks better identify the convoy. But, they said, Turkish officers instead directed the Americans who were remotely piloting the drone to fly it somewhere else. U.S. officials said compliance with the Turks’ request was standard procedure.

As darkness fell, Mr. Encu said, the men in the caravan heard the dull hum of Herons—the Israeli-made surveillance aircraft used by Turkey and less sophisticated than U.S. drones.

Then Turkish warplanes appeared. “It was like a lightning bolt,” Mr. Encu said. “I saw a bright light and the force of the explosion threw me to the ground…When I turned my head I could see bodies on fire and some were missing their heads.”

The strikes lasted for about 40 minutes, survivors said. Of the 34 men killed, 11 were members of Mr. Encu’s extended family. It was the largest number of Kurdish civilians killed in a single attack in Turkey’s long conflict with the region’s militants.

Rescuers dug for corpses under a collapsed mountain ridge. They wrapped body parts and loaded them on a trailer that was towed to the nearest village, according to accounts of residents and local officials.

The killings sparked clashes between hundreds of stone-throwing protesters and the police in Kurdish parts of Turkey. In the town of Uludere, Mayor Fehmi Yaman charged that the attack marked the latest in a series of government efforts to intimidate the local population, much of which supports Kurdish militancy.

“The military knew these people were civilians. It was a deliberate attack,” he said. “The government has tried all means of suppression, which have failed, and now they tried this.”

The Turkish military initially said it ordered the strike because the convoy moved along a pathway frequently used as a staging point for attacks by the PKK. Turkey’s government and its armed forces both have open investigations into the matter.

Turkey’s military didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment for this article. Turkey’s Prime Ministry, Interior Ministry and Defense Ministry said they would neither comment on the incident nor on questions over the scale of military cooperation between Turkey and the U.S.

The killings threaten to spoil efforts to forge a Turkish-Kurdish consensus for a planned new constitution expected to partly address the issue of rights for the Kurdish minority.

A former senior U.S. military official, involved in sharing intelligence with Turkey before the December attack, said he and fellow officers were sometimes troubled by Turkish standards for selecting targets. The former official said Turkish officers sometimes picked targets based on a notion of “guilt by association” with the PKK.

A current U.S. intelligence official defended the partnership. “That is going to be the exception. It is a horrible exception. It’s a tragic exception,” he said of the caravan strike. “But the vast majority of efforts to expand our information sharing and to work with our partners and allies around the world are going to have positive outcomes.”

U.S. personnel work in the Ankara Fusion Cell, in part, to monitor Turkey’s use of U.S. intelligence, U.S. officials said.

Turkish officials have assured the U.S. of their measures to avoid civilian casualties. They say privately that Predator drones help reduce attacks on the PKK using less precise weapons, such as artillery.

But U.S. officials say such mistakes are feeding a debate within the intelligence community and the Defense Department about setting better guidelines for sharing of U.S. intelligence.

Intelligence officials are divided on the issue. Some say the U.S. should withhold intelligence if it believes an ally might abuse the information. Others warn new rules could slow intelligence sharing during emergencies.

In Uludere, December’s events continue to reverberate. Local men have reduced cross-border smuggling trips, slowing the local economy.

Monuments to the dead have sprung up in villages. In Gulyazi, home to 13 of those killed, a 30-foot-high tent shelters a memorial where residents left handwritten messages next to portraits of the dead.

On the outskirts of one village, widows and bereaved mothers gather regularly. One day last month, scores of women marched along a dirt track to a makeshift cemetery where many of the dead were buried.

Fatma Encu, a cousin of Servet Encu, clutched a framed portrait of her eldest son, Huseyin, who was killed at age 19. “I don’t want compensation,” she said. “I just want the murderers to be found and punished.”

Chief of the Turkish general staff, Necdet Ozel, said the military was sharing information with prosecutors, according to a Turkish news agency. “We are not hiding anything,” he said.

—Ayla Albayrak and Siobhan Gorman contributed to this article.

Write to Adam Entous at [email protected] and Joe Parkinson at [email protected]

A version of this article appeared May 16, 2012, on page A1 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: Turkey’s Attack on Civilians Tied to U.S. Military Drone.

Leave a Reply