Op-chart: Turkey’s changing world

Editor’s Note: Soner Cagaptay is a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Hale Arifagaoglu is a research assistant at the Institute. Bilge Menekse is a former research intern at the Institute.

By Soner Cagaptay, Hale Arifagaoglu and Bilge Menekse – Special to CNN

Over the course of the 20th Century, Turkey’s world became increasingly Eurocentric. The country joined European and broader Western institutions, such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), while also moving to become a member to the European Union (EU).

Over the course of the 20th Century, Turkey’s world became increasingly Eurocentric. The country joined European and broader Western institutions, such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), while also moving to become a member to the European Union (EU).

Today, however, the country’s single-minded European trajectory appears to be a thing of the past. Turkey, which has experienced phenomenal economic growth in the past decade, no longer feels content to subsume itself under Europe.

Since 2002, the Turkish economy has more than doubled in size, reaching a magnitude of $1.1 trillion. Gone is the Turkey of yesteryear, a poor country begging to get into the EU.

Enter the new Turkey: A country that feels confident, booming as the world around it suffers from economic meltdown. In the third quarter of 2011, the Turkish economy grew by a record 8.2%, outpacing not only the county’s neighbors, but also all of Europe.

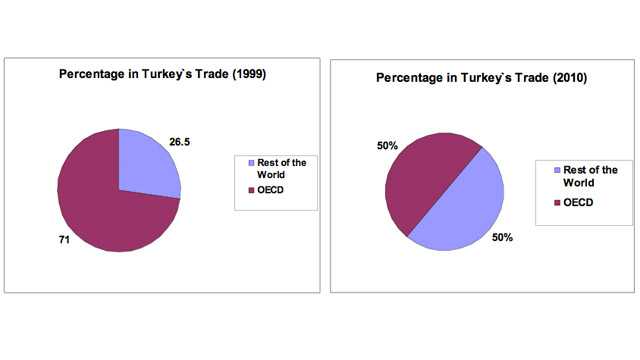

Europe’s economic doldrums coupled with Turkey’s new trans-European vision under the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government means that the country’s traditional commercial bonds with Europe are eroding while its trade links with the non-European world flourish. Accordingly, the Turks are increasingly trading with the non-OECD world (see the chart above).

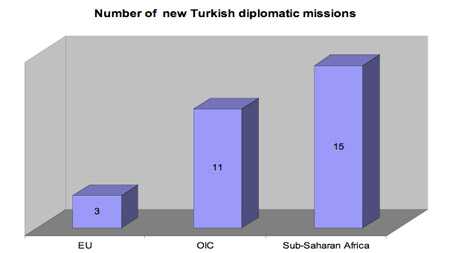

Paralleling this trend, Ankara has pursued a foreign policy that transcends Turkey’s old European focus.

The AKP’s vision of reaching beyond Europe politically is now Turkey’s vision as well. The following graph shows the number of new diplomatic missions Turkey has opened up since the AKP came to power in 2002:

Source: Turkish Republic Ministry of Foreign Affairs official website ). OIC stands for Organization of Islamic Conference.

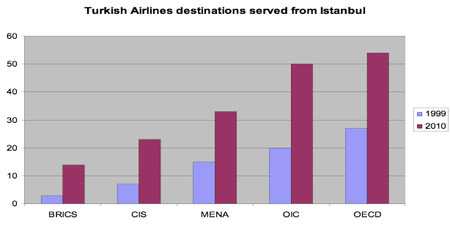

If Turkey is no longer trying to fit into Europe, then what is it doing? The best way to describe the new Turkey is as a “Eurasian China” – a country that is aggressively trading with the entire world while building connections to distant destinations. The next graph compares direct destinations served from Istanbul by the country’s flagship carrier, Turkish Airlines, in 1999 and 2010:

Source: Turkish Airlines official website ). MENA stands for the Middle East and North Africa. CIS stands for the Commonwealth of Independent States, including Russia and former Soviet states.

Is the “Eurasian China” model sustainable? This requires the Turkish economy to keep humming along and the country’s politics to remain relatively stable.

There is a foreign policy angle at work here: Turkey is relatively stable at a time when the region is in upheaval. This, in turn, attracts investment from less-stable neighbors like Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Investors are looking for a stable economy. Ultimately, political stability and regional clout are Turkey’s hard cash. Its economic growth and ability to rise as a “Eurasian China” will depend on both.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of Soner Cagaptay, Hale Arifagaoglu and Bilge Menekse.

via Op-chart: Turkey’s changing world – Global Public Square – CNN.com Blogs.