By MARC CHAMPION in Istanbul and CAROL E. LEE in Ankara

Vice President Joe Biden called on Turkey to join new sanctions against Iran, testing the limits of a U.S.-Turkish alliance that has improved dramatically as fallout from the Arab Spring drives Ankara into growing competition with Tehran.

Arriving in Ankara from Iraq, Mr. Biden also thanked Turkey for what he described as its “real leadership” in applying pressure to Syria, just days after Ankara announced its own sanctions on the regime and called for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to step down.

The vice president began his two-day visit at a time when Turkey has fallen in step with core U.S. foreign policies in the region—specifically toward Syria and Iran—and has become one of Washington’s most active foreign-policy allies, despite continued differences over Israel.

That is in stark contrast to last year, when Washington was gripped by debate over whether Turkey, a key North Atlantic Treaty Organization member, was turning east, away from its U.S. and European allies. Turkey triggered particular anger by voting in June 2010 against U.S.-backed sanctions on Iran at the United Nations Security Council.

In a question-and-answer interview published Friday in one of Turkey’s main daily newspapers, Hurriyet, Mr. Biden invited Turkey to join another round of sanctions aimed at Tehran’s nuclear program.

“Putting pressure on Iran’s leadership is necessary to secure a negotiated settlement, and that is why we encourage our partners, including Turkey, to take steps to impose new sanctions on Iran, as we have continued to do,” Mr. Biden told the newspaper.

There is little sign that Turkey is ready to join the U.S. and allies such as the U.K. in applying potentially crippling sanctions.

After meeting with Turkey’s President Abdullah Gul in Ankara on Friday, Mr. Biden flew to Istanbul. He was due to meet Saturday with Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who is recovering from an operation.

A senior U.S. administration official said the issue of Iranian sanctions didn’t come up in Mr. Biden’s two-hour meeting with President Gul. Neither did the two men discuss the possibility, floated by France, of creating an internationally protected buffer zone inside Syria along its border with Turkey.

Mr. Biden told Mr. Gul he believes Iran’s influence is declining across the region because of its nuclear ambitions, as well as other recent perceived missteps, such as Tuesday’s assault on the British Embassy in Tehran.

Analysts say Turkey’s increased cooperation with Washington is in large part due to fallout from the Arab Spring that continues to roil the Middle East and has pushed Ankara into increasingly open competition with Tehran.

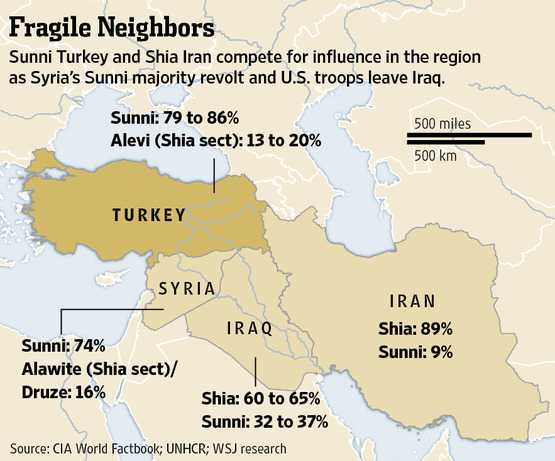

Turkey and Iran have chosen opposite sides in Syria as the country has descended into violence, with Tehran continuing to back the Assad regime and Turkey, the opposition. At the same time, a tacit competition for markets and influence in common neighbor Iraq also threatens to become more acute as U.S. troops leave.

Related Video

- Funerals, Protests in Syria (12/01/2011)

- U.K. Orders Iranian Embassy Closed (11/30/2011)

- U.S. Places New Sanctions on Iran (11/21/2011)

- What Are U.S. Options on Iran? (11/10/2011)

“In a month’s time, the U.S. will leave Iraq. To have three of your neighbors as either Iran, or [in the case of Iraq and Syria] supported by Iran, should not be comforting for Turkey,” said Soli Ozel, professor of international relations and political science at Bilgi University, in Istanbul.

The U.S. administration official said Mr. Biden had said in his meeting with President Gul that he didn’t believe Iraq would fall under Iranian control once U.S. troops leave.

Iran was particularly angered—and the U.S. gratified—by Ankara’s decision in September to agree to host a radar for NATO’s anti-missile defense system, which is directed primarily at Iran. On Saturday, a general in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, Amir Ali Hajizadeh, warned that should any military strike be made on Iran, Tehran would target Turkey’s NATO radar.

Turkey this week also appeared to choose sides in Iran’s dispute with Britain, condemning Tuesday’s semiofficial sacking of the British Embassy in Tehran by hard-line students.

But Turkey is wary of escalating actions against Tehran. It shares a long border with Iran and is potentially exposed to a revival of support, from Tehran and Damascus, for Kurdish rebels battling Turkish troops.

Ankara also doesn’t want to fuel a Shiite-Sunni confrontation on its borders. Iran and Iraq are majority Shiite, while Turkey is mainly Sunni. Syria, meanwhile, is governed by a minority elite of Alawites, a Shiite sect.

“There are limits to what Turkey can do,” said Mr. Ozel. “You still get 20% of gas from Iran, you still ship your goods to Central Asia through Iran and there are still about 1 million Iranian tourists coming over the border.”

The storming of the British embassy appears to have been triggered by Britain’s decision to ban U.K.-based banks from doing business with Iran’s central bank, creating potential difficulties for Tehran in financing energy exports. On Thursday, the U.S. Senate voted in favor of a ban that would penalize foreign banks operating in the U.S. that do business with Iran’s central bank.

Corrections & Amplifications

On Thursday, the U.S. Senate voted in favor of a ban involving foreign banks that do business with Iran’s central bank. An earlier version of the story said it was Tuesday.

Write to Marc Champion at marc.champion@wsj.com and Carol E. Lee at carol.lee@wsj.com