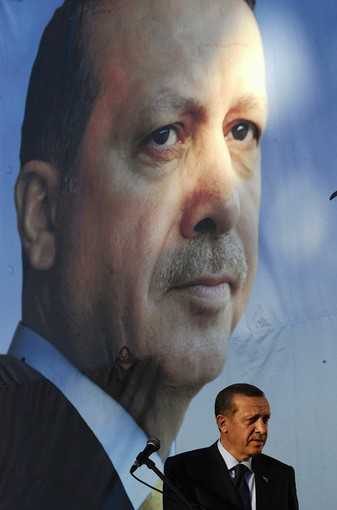

Many advisors to the president see Erdogan’s government as a possible model for others in the Middle East. But the Turkish premier’s feud with Israel and a tendency to make threats are problematic.

By Paul Richter, Los Angeles TimesOctober 10, 2011, 8:41 p.m.

In the space of a few weeks this summer, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan slammed President Obama’s approach to Mideast peacemaking, threatened to block U.S. business from drilling for oil and gas in the Mediterranean, and warned he might mobilize Turkish warships to protect activists sailing to Gaza against America’s chief regional ally, Israel.

Yet when Obama met Erdogan on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly meeting last month, he once again gave him more face time than any other world leader. Erdogan, Obama declared as the two headed to a 105-minute meeting, “has shown great leadership.”

The attention lavished on the leader of Turkey reflects the importance of the moderate Muslim power to an administration seeking to retain influence in a turbulent part of the world. Many Obama advisors see Erdogan’s government, with its pro-business bent and tolerance for secular expression, as a possible model for others in the Middle East. The president has logged more phone calls to Erdogan than to any world leader except British Prime Minister David Cameron.

Yet Erdogan’s mercurial temperament and propensity for rhetorical threats makes dealing with him an awkward challenge.

U.S. officials praise Turkey for its help in organizing a new government in Libya, isolating a brutal Syrian regime at war with domestic opponents, and cooperating on a Western missile defense system to contain a potential threat from Iran. But they have been distressed by the way Turkey has recently feuded with Israel, squabbled with neighbors and the European Union, and called out its navy to defend its energy claims in the Mediterranean.

“They’ve been lighting matches around kindling that is pretty dry,” said a U.S. diplomat in the region.

Obama has used virtually every diplomatic tactic available to deal with a partner he considers indispensable but doesn’t always understand. He has tried sweeteners, such as drone aircraft to spy on Kurdish militants. And he has resorted to flattery: He phoned Erdogan last year to rave about a Turkish basketball tournament.

But at other times he has felt compelled to be blunt, such as when he complained in a two-hour meeting with Erdogan last year about Turkey’s vote against proposed United Nations sanctions on Iran.

Adding to the friction, Turkey’s conflict with Israel and other moves have begun to mobilize opposition in the U.S.

A bipartisan group of seven senators, including Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.), No. 3 in the Democratic Senate leadership, wrote Obama to demand a U.S. response to Turkish moves that “call into question its commitment to the NATO alliance, threaten regional stability and undermine U.S. interests.” U.S. officials have warned the Turks that Congress could try to block access to weapons it badly wants.

Eric Edelman, U.S. ambassador to Turkey from 2003 to 2005, says he has been shocked to see Obama cajoling a nation that has been working against key U.S. diplomatic goals.

Erdogan “gave them a poke in the eye — and he got a [long] meeting,” Edelman said.

Erdogan has led Turkey since 2002 as head of the Justice and Development Party, which is rooted in Islam. Backed by a roaring economy, he has set vaulting ambitions to expand Turkey’s leadership of the Arab world, and strengthen economic and political ties to the East, even while preserving the nation’s valuable security relationship with the U.S.

But these goals often work against one another. Turkey’s ties to the U.S. have been strained by its feud with Israel, which has sent the Obama administration into an unsuccessful scramble to make peace between two U.S. allies who used to be friends.

U.S. officials understand that Erdogan remains bitter about Israel’s May 2010 commando attack on a flotilla organized by activists in Turkey to bring aid to the Gaza Strip, which is under blockade by Israel. Eight Turks and a Turkish American died in the attack. Erdogan threatened recently to dispatch Turkish warships if Israel threatened any Turkish ships headed to Gaza.

But it is harder for U.S. officials to accept the way Erdogan has escalated his conditions for normalizing relations with Israel, now demanding an end to the blockade of Gaza as well as a formal apology for the deaths of the Turkish citizens. U.S. officials are nervous about what they see as a populist campaign to build an international reputation on the back of anti-Israel rhetoric.

Already considered the most popular politician in the Arab world, Erdogan thrilled crowds last month during a trip to Egypt, Tunisia and Libya when he complained that Israel was “the West’s spoiled child.”

He campaigned to round up votes in the U.N. Security Council for official recognition of Palestine as a full U.N. member state, a move the U.S. was trying desperately to block. As American diplomats buttonholed officials at the U.N. last month to urge them to vote no, Turkish officials were meeting with some of the same countries nearby to pressure them to do the opposite.

Erdogan made it known that in his meeting with Obama, he told the president that Obama’s signature peacemaking initiative had failed, and pointedly read to the president portions of the 2010 speech in which Obama had declared there would be a Palestinian state within a year.

Turkey’s booming 9% growth rate has been a source of its growing influence, and the government has worked hard to preserve it, though it has led to regular collisions with neighbors and world powers. Turkey has taken advantage of the economic weakness of such neighbors as Iraq and Syria, and has opened trade with Eastern neighbors including Iran.

In recent days, Turkey’s claims over disputed oil and gas fields in the Mediterranean have led to a flare-up with Washington, as well as with Cyprus, Israel and Greece, which are among several countries with claims on energy deposits in the sea.

Turkey has demanded that Cyprus halt plans to have a U.S. energy company drill for gas in waters claimed by Cyprus. Turkey said the drilling threatened a U.N. effort to reunify Cyprus, which is divided between ethnic Greek and Turkish enclaves, and Ankara has sent warships into the zone.

Administration officials, led by Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, have rushed to the defense of the U.S. firm, Noble Energy, that is to conduct the drilling, and have told the Turks that they view the Turkish move as a threat to American business interests.

Cyprus has also been a source of conflict with the European Union. Erdogan said Turkey would break off talks on accession to the union if Cyprus was given the rotating presidency, as is planned.

Turkey has been caught between its desires to remain a member in good standing of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and to strengthen its economic and political ties to Iran.

It balked for months at NATO’s request to accept a defense radar on its territory for a system aimed at blocking the missile threat from Iran. Last month it agreed to accept a U.S.-built site, to the delight of U.S. officials.

But that came only after NATO officials made it clear, said one alliance official, that “if we didn’t put it there, we’d just put it in another country nearby.” Turkish officials continue to publicly insist that data from the radar won’t be provided to Israel — though U.S. officials say it will.

U.S. officials praise Turkey’s cooperation in helping organize a new order in Libya with the ouster of Moammar Kadafi’s government. But Turkey initially fought proposals for NATO intervention, in part because of worries about Turkey’s $15-billion investment in Kadafi’s state, and the 25,000 Turks then working there.

Turkey has become outspoken in its opposition to Syrian President Bashar Assad’s violent crackdown on antigovernment demonstrators, after begging Obama in July to delay calling for Assad to step down.

But though Erdogan has denounced Assad’s crackdown as “savage,” he has tried to avoid disrupting Turkey’s valuable trade and investment ties to Syria. Turkey is expected to soon impose a round of economic sanctions on Syria, but analysts predict they won’t go as far as the White House would prefer.

U.S. officials say they stay in close touch with Turkey, in part to avoid surprises. Last year, for example, Pentagon officials were alarmed to learn that Turkey had conducted military exercises with China, with no advance notice, raising questions about its plans with NATO.

There is consensus among Western diplomats and regional specialists about the value of Obama’s efforts to help expand Turkey’s regional role and anchor it to the West, especially at a time when Turkey’s chances for joining the European Union appear to have faded. Yet the ties may be somewhat short of the “model partnership” that Obama and Erdogan refer to.

Henri Barkey, a Turkey expert and former State Department official, says that although U.S. officials have gotten some of the commitments they most wanted from Turkey this year, others, such as restoration of its former strong relationship with Israel, may be out of reach.

“They won’t convince Turkey not to lead an anti-Israel bloc in the Middle East,” said Barkey, now with Lehigh University. “Not going to happen.”

Leave a Reply