By Jack Grove

Debate has been further inflamed by claims that Turkey has paid off historians. Jack Grove reports

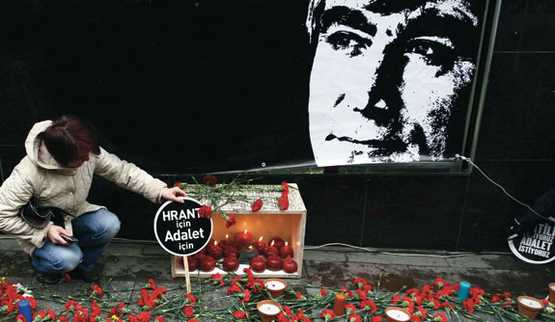

Not forgotten: a protester places a banner, ‘For Hrant, for Justice’, outside the Agos newspaper offices during a demonstration to mark the third anniversary of editor Hrant Dink’s assassination

Few academic subjects are as politically explosive as the dispute over the mass killings in Armenia.

Almost 100 years after the alleged atrocities of 1915-16, arguments still rage over whether the deaths of between 600,000 and 1.5 million Armenian civilians constitute genocide.

Most historians agree that Ottoman Turks deported hundreds of thousands of Armenians from eastern Anatolia to the Syrian desert during the First World War, where they were killed or died of starvation and disease.

But was this a systematic attempt to destroy the Christian Armenian people? Or was it merely part of the widespread bloodshed – including the deaths of innocent Turkish Muslims – in the collapsing Ottoman empire?

Unlike most scholarly disputes, however, this clash goes far beyond the confines of academic journals and conferences.

More than 15,000 Armenian-Americans marched through the streets of Los Angeles in April 2008, calling for Turkey to apologise for its “ethnic cleansing”, and Turkey recalled its ambassador to the US after a congressional committee narrowly voted to recognise the episode as genocide.

The Turkish newspaper editor Hrant Dink was assassinated by a 17-year-old nationalist in 2007 after criticising the country’s denialist stance.

Before Dink’s death, such claims had resulted in his being prosecuted for “denigrating Turkishness”. The Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk was also prosecuted for making similar claims.

Denialist claims

Now a leading historian has further inflamed debate by claiming that academics have been paid by the Turkish foreign ministry to produce denialist works.

Taner Akçam, associate professor at Clark University in Massachusetts, told a conference at Glendale Public Library, Arizona, in June that he had been informed by a source in Istanbul, who wished to remain anonymous, that hefty sums have been given to academics willing to counter Armenian genocide claims.

Although Akçam claims he did not name any historians explicitly, five academics have threatened legal action, saying they were implicated and have therefore become targets for extreme Armenian nationalists.

Akçam denies he has defamed anyone, adding that he has been the target of a “hate campaign” for many years for his work on genocide.

“I never mentioned any names, nor accused anybody,” he says.

“I only shared information that I learned when I was in Istanbul – this was very general information without names.”

Beyond the legal writs, however, the episode has raised questions of whether free historical investigation of the genocide claims can ever take place amid the frenzied Turkish-Armenian political climate.

Akçam, who is often described as the first historian of Turkish origin openly to acknowledge and research the genocide, believes pressure from Ankara has made it impossible for Turks to look into the subject at home.

“There is no direct pressure on academia, in the sense that the government doesn’t issue bulletins or communiques to stay away from the subject.

“But if one works on Armenian genocide and uses the term, one would lose one’s job immediately.

“This is the very reason why almost none of the scholars use the term ‘genocide’, even though there are a lot of journalists and public intellectuals using this term.

“It is very risky to focus one’s work on this area, let alone to get funded by the state.

“If I wanted to work in Turkey, I would not be able to find a job at any university. None of the private universities can hire me as they would be intimidated by the government and public pressure, especially the media.”

However, Jeremy Salt, associate professor in history at Bilkent University, Ankara, believes the issue is no longer taboo.

“I have been in this country quite a long time and all kinds of things that could not be discussed 10 or 15 years ago are now discussed openly,” he says.

“Ten years ago public criticism of the army was unthinkable – I myself got into trouble for this. Now as part of the Ergenekon inquiry (into an ultra-nationalist group accused of trying to overthrow the government), retired generals have been arrested and the prominence of the army in politics has been shrunk to a shadow of what it was.”

Skewed perspectives

Indeed, he believes the influence of Armenian nationalists – including the powerful Armenian diaspora – has also skewed discussion of the era and prevented impartial consideration of the mass deaths.

“As far as the Western cultural mainstream is concerned, there is virtually no comprehension, outside (the battle of) Gallipoli…of the scale of the catastrophe that overwhelmed the Ottoman Empire. About 3 million civilians died.

“They included Armenians and other Christians, Kurds, Turks and other Muslims of various ethno-national descriptions.

“They died from all causes – massacre, malnutrition, disease and exposure. Armenians were the perpetrators as well as the victims of large-scale violence. No one comes out of it with clean hands.

“These are the facts that any historian worth his salt will come across, but which generally are skated over or played down, or treated as propaganda by writers who shape their narrative according to need and not according to where the search for truth leads.”

Diaspora measures

Hakan Yavuz, professor of political science at the University of Utah, and one of the academics threatening to sue Akçam, also criticised the role of the Armenian diaspora.

“In the late 1970s, a group of radical Armenian nationalists placed a bomb just outside (Ottoman historian) Stanford Shaw’s home in California. Many historians decided to steer clear from the discussion – in other words, the culprits succeeded in reaching their aim.

“The Armenian diaspora has been the key obstacle to advancing the debate over the causes and consequences of the events of 1915. It has invested lots of its time and resources to promoting the genocide thesis and silencing those who question their version.

“One may conclude that the Armenian diaspora seeks to use the genocide issue as the ‘societal glue’ to keep the community together.

But Akçam disagrees: “At the same time, the Turkish government’s heavy-handed policies are not helpful at all. If there were no diaspora effort, this issue would hardly be a topic in Turkey. Their efforts help to keep the topic alive and on the agenda.”

The legal action against Akçam threatened by Yavuz is not the first such case in the fraught world of genocide studies.

In March, a judge dismissed a claim by the Turkish Coalition of America, which argued that it had been defamed by the University of Minnesota’s Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

Judge Donovan Frank ruled that the department had acted legally when it created a “blacklist” labelling the coalition’s website as unreliable for academic use because it contained material denying the Armenian genocide.

But might the prospect of thawing relations between Armenia and Turkey finally help to bring about a reconciliation of this issue – or at least the possibility of debate free from political interference?

Akçam is hopeful. “If Turkey opens the borders and normalises its relations with Armenia, this could have a very positive impact on the research on genocide or different aspects of Armenian studies,” he says.

“The normalisation of the relations between both countries could be an important step for more independent academic work in the field.”

Leave a Reply