Thomas Seibert

ISTANBUL // Six decades after it came into force, a law protecting the memory of the republic’s founder Mustafa Kemal Ataturk still has the power to rock careers, trigger prison sentences and block access to YouTube.

Earlier this year, a court in eastern Anatolia acquitted Ahmet Ayicil, a professor who faced up to three years in prison. He had been charged for allegedly saying in his class that Ataturk was a heathen “idol”.

Denounced in 2007 by a student who did not attend the class personally, Prof Ayicil went through a lengthy trial based on Law Number 5816, a special provision that makes it a crime to “denigrate the memory of Ataturk”. Destroying, damaging or desecrating Ataturk busts or monuments carries sentences of up to five years.

The court found Prof Ayicil not guilty because of a lack of evidence. But in 2008, Atilla Yayla, another professor, was given a suspended sentence of 15 months in prison for criticising Kemalism, a secularist ideology based on Ataturk, and for telling a public forum that the EU, which Turkey wants to join, would be wondering why there were “pictures of this man” in every Turkish office.

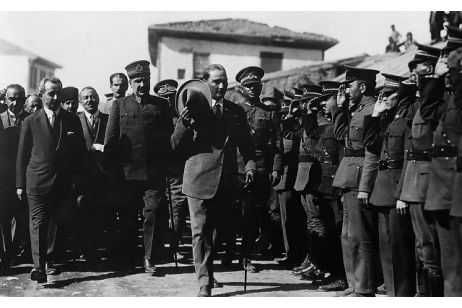

The law was passed by Turkey’s parliament on July 25, 1951, and came into effect six days later. A former general of the Ottoman army who is credited with erecting Turkey’s republic from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire in the early 1920s, Ataturk is a national hero for most Turks. His portrait hangs in every school and public office and is routinely shown during public functions. Sometimes referred to as the “great leader” in official speeches, Ataturk’s image adorns coins and lira bills.

But while Turks in general revere Ataturk, who died in 1938, some wonder whether the time has come to abolish or amend regulations like Law No 5816 because they limit free expression and are unsuitable for a modern democracy.

“It is not a modern law,” Halil Dogan, the president of the Democratic Lawyers Association, a group of lawyers campaigning for democratic reform, said in a telephone interview this week. “Of course everybody should be protected against denigration, but Turkey’s current laws are sufficient for that.”

Mr Dogan stressed that, as with every law, the interpretation and implementation of Law No 5816 was the key. Several high-profile investigations and decisions by prosecutors and courts, based on suspected defamations of Ataturk’s legacy, have been denounced as attempts to stifle critics.

One of the most controversial cases was a verdict blocking nationwide access to YouTube on the grounds that it included a video denigrating Ataturk. The ban was lifted in October last year, two-and-a-half years after it came into effect, because the video clip was erased. “The YouTube interpretation [of the law] was definitely a step against the freedom of speech,” Mr Dogan said.

In another example that made headlines, Ipek Calislar, a writer, was tried in Istanbul for writing in a book that Ataturk disguised himself as a woman once to escape a planned attempt on his life. Ms Calislar was acquitted in 2006.

Three years later, Can Dundar, a journalist and filmmaker, was questioned by prosecutors after complaints against Mustafa, a documentary about Ataturk’s life that depicted him as a sometimes lonely man who drank alcohol. A comic book titled Genc Mustafa, or Young Mustafa, which included a scene in which Ataturk was beaten as a young man, triggered a trial against the publishers earlier this year. The case is ongoing.

But Mr Dogan said he was confident that the law may be changed because Turkey, which has brought in several reforms for its EU bid, was strengthening the rights of its citizens. “I think that freedom of speech will be widened, I see a chance to change the law,” he said.

The issue of Ataturk’s legacy is expected to come up during talks about a new constitution for Turkey, due to begin after parliament returns from its recess on October 1. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) as well as the two biggest opposition parties have formed committees to prepare for the talks, the daily Vatan reported this week.

Turkey’s constitution was drawn up under military rule in 1982 and is widely considered outdated and anti-democratic. One of the problems facing lawmakers, academics and non-governmental groups discussing the new constitution is the question of whether the reference to “Ataturk nationalism” as the state ideology should be included in the new text.

Some legal experts of the AKP have suggested that the new constitution should be free of references to “Ataturk nationalism”, Kemalism or other ideologies. But the secularist Republican People’s Party, the main opposition party, has said it wants to keep the first three paragraphs, which describe Turkey as a republic committed, among other things, to “Ataturk nationalism”.

tseibert@thenational.ae

via Some Turks ready to abolish law that protects memory of Ataturk – The National.