By Katinka Barysch

The Daily Star

The outcome of the Turkish parliamentary election on June 12 was a foregone conclusion. For a third time, voters rewarded the ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, and its popular leader, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, for presiding over almost a decade of economic growth and Turkey’s rise as a regional power.

However, a Turkey ruled by an overly strong and increasingly intolerant AKP is less likely to continue with reform and democratization at home. It would hardly be an inspiration for the millions of Muslims striving for freedom in the Middle East and North Africa.

The uprisings in its neighborhood will force the next Turkish government to make some tough choices. These are best made in a political system that has strong checks and balances and allows for open debate.

The next Turkish government will remain officially opposed to Western intervention into Arab countries – as it was initially when the United Kingdom, France and the United States decided to protect the Libyan rebels.

It will also remain cautious about calling for the demise of autocratic regimes around its borders, fearing political instability, a resurgence of Kurdish separatism and refugee flows. However, sooner or later Erdogan will have to acknowledge that the time for dictatorships in the Middle East is over if Turkey is to maintain its regional leadership and credibility.

During his election rallies, Erdogan promised to use his renewed mandate to adopt a new Constitution and improve Turkey’s infrastructure. Foreign policy has played a secondary role.

Erdogan is unlikely to take the steps necessary to unfreeze Turkey’s European Union accession talks as long as Cyprus, France and other EU members keep blocking progress on the European side.

Instead, Ahmet Davutoglu, Turkey’s clever and energetic foreign minister, will continue his efforts to implement a “zero problem with the neighbors” policy. Even the main opposition party, the secularist Republican People’s Party (CHP), promised to stay on a similar foreign policy course in the unlikely event of a victory, although it vowed to improve strained relations with the U.S. and Israel.

Nevertheless, Turkey’s foreign policy will inevitably change in coming years – and the election will have been crucial in determining how. Turkey matters hugely for the regions to its east and south: both for what it is, as a model and inspiration for the Muslim world, and what it does, a hyperactive player in a troubled neighborhood.

Most Turks dismiss the idea of their country being a model for the transformations taking place in North Africa and the Middle East. Yet there’s no doubt that many people in the Arab world and beyond are inspired by the fast-growing, predominantly Muslim and secular democracy that has started to address intractable minority issues.

Turkey’s democracy is far from flawless. True, elections are free and mostly fair. Civil liberties, minority rights and the status of women have all been strengthened. And the army no longer plays a strong role in politics. Yet the ruling AKP, just like the CHP before it, stands accused of using the judiciary, the ministries and other bits of the state apparatus to tighten its grip on power, hold down opponents and reward cronies.

The political scene is deeply split, while intolerance bordering on paranoia poisons the political atmosphere. Some 60 journalists now languish in jail, many on spurious charges of wanting to overthrow the constitutional order or split the country. About 10,000 cases against writers and broadcasters are still pending.

For many Turkey watchers in the West, these democratic shortcomings threaten to invalidate Turkey’s EU applications. But for most people in say, Syria, Iran or Libya, Turkey probably still looks infinitely better than their own autocratic, poor, battle-weary countries.

In fact, Turkey’s imperfections might add to its appeal in the Muslim world. Few Egyptians or Tunisians appear to have much appetite for European or American sermons about the right way to build a democracy or market economy.

Turkey is seen as a country that grapples relatively successfully with familiar problems, such as how to combine democracy and religious authority, determine the military’s role in post-revolutions politics and enacting economic reforms that create jobs for an eager young population.

While proud of their achievements, Erdogan and Davutoglu have made a point not to lecture their neighbors about how to run their affairs.

Many previous governments in Ankara regarded their neighbors mainly as potential threats to Turkey’s territorial integrity and secular regime. By contrast, Erdogan has highlighted reconciliation, trade integration and people-to-people contacts.

Until recently, Erdogan managed to maintain close personal ties with autocrats such as Syria’s Bashar Assad, Iran’s Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Libya’s Moammar Gadhafi, while at the same time appealing to the so-called Arab street through his strident criticism of Israel and defense of the Palestinian cause.

Turkey also gained kudos trying to be an honest broker in some of the region’s more intractable conflicts, such as between Israel and Syria or Afghanistan and Pakistan, albeit with limited success.

Turkey’s “zero problem” policy started to look threadbare even before the Arab Spring. Its attempted reconciliation with Armenia has foundered, relations with Israel deteriorated while Turkey’s policy toward Iran upset its traditional Western allies. Turmoil in its neighborhood now forces Turkey to make hard choices.

With instability now on Turkey’s borders, in particular in Syria, security considerations once again are climbing the Turkish foreign-policy agenda. Erdogan was quick to call for political change in Egypt, a regional rival with which Turkey has scant ties, but he took time to criticize Gadhafi and Assad for unleashing their armies on their own people.

In the new political climate, Erdogan can no longer easily rub shoulders with the likes of Ahmadinejad while being a hero to millions of Muslims.

Many people in the Middle East and North Africa look to Turkey not only for inspiration but for active support in their struggle for freedom and prosperity. Turkey could be well placed to share its experience in building a multiparty democracy and functioning state institutions – but only if its democratization process continues at home.

Erdogan had hoped to gain a super-majority, allowing him to push through a new Constitution, as promised since 2007, without much input from the opposition. He was unable to achieve this.

Such an option would have further deepened Turkey’s pernicious political divide and set a bad example for neighboring countries threatened by sectarianism and political strife.

What’s more, many observers assume that the AKP would have sought to create a presidential system through the new Constitution, with Erdogan himself ascending to a strengthened presidency in a few years. For Turkey – an already a highly centralized country – this would have been a bad move.

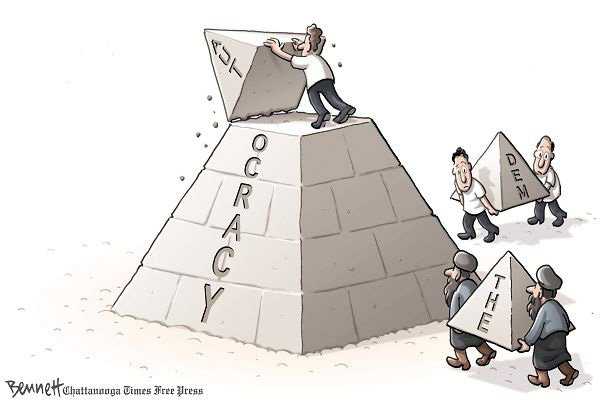

The result would not so much have been Islamization, as Erdogan critics often claim, but Putinization: a political system focused on one strongman with weak or nonexistent checks and balances, bad decision-making and a withering opposition.

Such a Turkey could not inspire its neighbors and it could hardly have been relied upon to help the Middle East on its path to political and economic openness.

Katinka Barysch is deputy director of the Centre for European Reform, an independent London-based think tank. This commentary is reprinted with permission from YaleGlobal Online (www.yaleglobal.yale.edu). Copyright © 2011, Yale Center for the Study of Globalization, Yale University.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Daily Star on June 17, 2011, on page 7.

Read more:

(The Daily Star :: Lebanon News :: http://www.dailystar.com.lb)