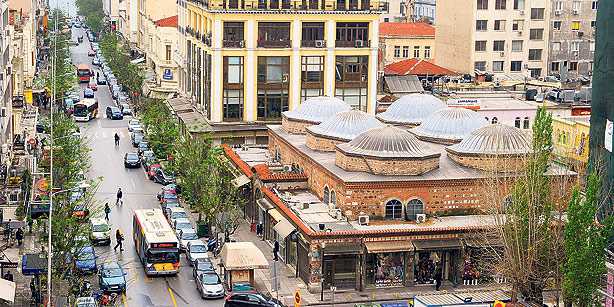

On the sea end of Thessaloniki’s Egnatia Boulevard, which cuts through the city from east to west, lies a small district with a children’s park that bears the same name as the district: Plateia Novarinou.

All of the “others” who inhabit Thessaloniki flock to these streets. Nikos Canis (Nikos Tzannis Ginnerup) is someone who would rather live here than in just any old neighborhood, and the classic sounds of the violin can be heard drifting from his windows down to the street below. In the middle of a small, high-ceilinged room is a tiled coffee table, and the walls around it are filled with musical instruments. Canis says, “Even though it might be happening slowly, Greek society is going through a period of rediscovering Ottoman culture.” As for him, Canis made his own personal discoveries on this front long ago.

Although the heaviness of the economic crisis that has afflicted Greece has been sitting over the country like a dark cloud lately, this city has embarked on a journey of self-discovery. As a city, Thessaloniki was once a city the Turks used for every new idea they had. However, it has long been forgotten, as a place where pashas were imprisoned and where armed political parties gathered. Jewish residents, who came on the invitation of the Ottoman sultans, were forced to bid this city farewell during Hitler’s time. As for the Greeks themselves, they often used Thessaloniki as a basis for constructing a national state.

These days Thessaloniki is trying to make a resolute return that will make up for all the time lost over the past years and is making its own calculations about how to return to the special status it once held.

The real sign of change came with the most recent local elections. Yannis Butaris was able to use his uniting personality to overturn the 25-year rule of the conservative New Democrat Party, by becoming mayor of Thessaloniki in the process. Mayor Butaris says that his greatest dream is to see Thessaloniki regain its multicultural aspect, noting that in the process he and his team wish to see the reality of the city — which existed for 500 years under Ottoman rule — return. Butaris refers to the past, and to not only the 500 years of Ottoman rule, but also to the Jewish character that developed in this city, saying: “All of the Turks, Jewish people, Greeks and Slavs brought a very multicultural dimension to this city. At the start of the 20th century, this city, which reflected a variety of cultures, had 12 different newspapers published in different languages — from Turkish to Greek, French to Hebrew.” Butaris talks about the past as he makes notes of plans for the future. He says the time has come to transcend false fears, asserting: “Why should I be scared of the Turks? What, are they going to come and try to take Thessaloniki?” Butaris is now promising that a spot once occupied by a monument representing Turks but which is now used as a car park, will be turned into a mosque and a new cemetery for the city’s Muslim population. This spot was where an important speech on freedom was once made, and perhaps once the mosque is built, it will remind people again of the “Hürriyete Hitap” (Address on Freedom) speech that was once delivered here.

Butaris notes that his work on all these fronts is appreciated by the residents of the city. He notes that overcoming bureaucratic blockades requires nothing but “perseverance, patience and desire.” With the recent economic crisis and the political turbulence that has arisen, many Greek politicians can barely make appearances on the street anymore.

As for Butaris though, with his arms tattooed all the way down to his hands and his earring in place, he is comfortable just hanging out with the youth of the city at the seashore and singing songs or accepting carnations from voters who see him in the street. In fact, the greatest supporters of the new Thessaloniki — which has also recently applied to be the 2014 European Youth Capital — appears to be the younger generation of the city. Yorgos Yourgiadis (31) of the civil society organization Youth in Action notes that what has been missing in Thessaloniki up until now are dreams and desire. The city, over the past years, seemed shrouded in darkness and just broken down. Yourgiadis describes the election of Butaris as a great opportunity for the city.

“Thessaloniki was not just the second most important city for Greece in history, but it was also important for the Byzantine and Ottoman empires.” The person who asserts the above is Ekatirini Michailidou, the deputy president of the city’s biggest company and of the Greek-Turkish Trade Chamber of Northern Greece. He says, “If you know what you want to do, this city has opportunities for you.” He also notes that Thessaloniki has stood not only as a gateway to Greece but also to the Balkans, to the rest of the world. His company, Leaf Tobacco, is today one of 50 businesses throughout Greece owned by the A. Michaelides Group, who laid its foundations in 1886 in northern Greece when the region was still an Ottoman state. The company now makes 135 million euros a year from export and is fourth in the world in terms of tobacco harvest and processing. The company is also active in 12 countries, and currently Michailidou is researching collaboration possibilities with Turkey concerning organic agricultural pesticides. At this point, Leaf Tobacco also markets pesticide free of animal by-products to many countries including Syria and Iran.

“I see more of a desire to make cooperative efforts with Turkey in Thessaloniki,” Michailidou said, also noting that he found the new Turkish Airlines (THY) Istanbul-Thessaloniki flights — which are to begin in the last week of May — a positive step towards furthering cooperation between the two cities.

Social scientist Despina Syrri notes that “Balkan countries have been engaged in trying to erase their Ottoman past in different ways when they went through the process of creating their own national states. But these were political choices of that era.” She suggests that the warmer ties and efforts to create friendships in recent years are part of a very natural process. Syrri says that because of her own family’s background, she herself feels very close to Turkey culturally and points to how the time has really come for Thessaloniki to re-enliven itself on matters of economy and tourism in particular.

Architect and musician Nikos Canis says that he has invested a serious interest in to learning more about Ottoman culture. He also says that he has not reached his position he holds today easily, but as a result of gaining experience. His interest in Turkey started in what he calls “difficult days.” He arrived in Turkey in 1988 and stayed for five years. He worked then as an architect in the Istanbul district of Kuzguncuk, and he also played music, from the classic kemençe (a small violin played like a cello) to the tambur (a classic Turkish instrument much like a mandolin), learning a lot about formal Ottoman music at the same time. He also started taking lessons at a music course in Central Anatolia, where he learnt how to play the bağlama (a stringed musical instrument from the eastern Mediterranean region), as well as studying Ottoman Turkish. Nowadays he has a group of friends who put on concerts where they play the classic kemençe all over Greece. This group also plays at festivals. As Canis sees it, there is no Turkish or Greek music, but rather Ottoman music. He is saddened by the lack of a museum about Ottoman civilization in Thessaloniki. But he sees the two-book series published by the Greek Culture Ministry on architectural styles of the Ottoman period as a great start to allowing people to start learning more about the past.

Canis notes that fears and preconceptions must be put aside now and says: “When you look for an enemy, you will never have any troubles finding one. It was the Turks who were enemies yesterday, and tomorrow it’ll be the Albanians.”

One of Greece’s leading Turkologists, Professor Vasilis Dimitriadis, is known for starting speeches to his students with these words: “Forget every story and distorted recounting of what you have heard about Turkey up until now. Turkey is our neighbor and a friendly country with whom we are obliged to develop relations.” Dimitriadis worked for 30 years at the Historical Archives of Macedonia in Thessaloniki and has written many scholarly works concerning the Ottoman period. In fact, his “Thessaloniki Topography during the Ottoman Era (1430-1912)” is widely accepted as an important reference source for people interested in these issues.

Theology professor Grigoris Ziaka asserts that Europe has tried to replace the centuries of culture that saw people actually living together with the concept of “humanism,” and notes that he himself first encountered Islam when he visited the Greek cities of Gümülcine and İskeçe when he was in his twenties. He recalls: “When I visited mosques, people would invite me in lovingly. I would ask whether the fact that I was not Muslim bothered them. And I never got a response that indicated that I bothered them at all. I found humanism and true brotherhood in these relationships.”

In 1973 a translated version of the Mevlana done by Ziaka was published in Greece. Later, Ziaka studied the concepts of “evi” as he found them in Mevlana and Ibn Arabi. He then also started writing about the Quran and the life of the Prophet Muhammad. His short book on Islam is very much like a catechism.

As one of the most important intellectuals to come out of western Thrace recently, Ibrahim Onsunoğlu believes that Thessaloniki has always been a magnetic center in the region. Onsunoğlu has worked for many years as a psychiatrist in Thessaloniki and points out that many important revolutions have actually had Thessaloniki as their starting points. Both Atatürk and Nazım Hikmet were born here as well. And the city is not only the starting point for the first socialist movement in the Balkans, but also the place where the first-ever Turkish newspaper was published. In fact, the Yeni Asır (New Century), a newspaper still published in Izmir, actually began in Thessaloniki. Another interesting note is that the feminist and women’s movement that started in the Ottoman era also began here. But even though Thessaloniki was incredibly cosmopolitan throughout the 19th century, it turned into much more of a homogenous city after the majority of its Turkish and Jewish residents left. At that point, it really became a national state. When you look at photographs of Thessaloniki taken prior to 1912, you see minarets rising from every corner of the city. After all that, though, only one minaret was left: Rotondo.

For the Turks of western Thrace, Thessaloniki has always been the city where teachers who come to teach in their schools are trained. The Thessaloniki Private Pedagogical Academy, founded in 1968, used to send its graduates to teach in western Thrace. However the institution was shut down this year, but there is also the Macedonia-Thrace Muslims Educational and Cultural Association, which is still active.

Leave a Reply