BURAK BEKDİL

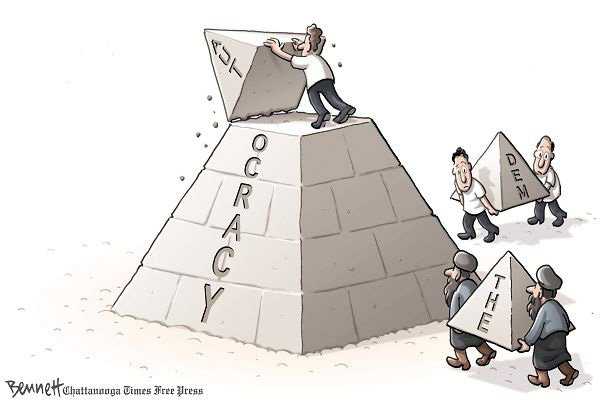

These days, Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey looks like a very good example of very bad democracy. The prime minister’s firm belief in uncompromising majority rule perpetually creates scenes reminiscent of the German Democratic Republic, or GDR, of the 1970s: the Turkish Stasi is as good as the East German one, if not better.

Sadly, the Turkish Stasi has only been incapable of finding the culprits behind a flurry of professionally-plotted, produced and released sex tapes, which practically ended the political careers of (so far) 11 top opposition politicians, including the former leader of the main opposition Republican People’s Party, Deniz Baykal.

On Friday, a friend told us what he had seen at the town center, Kızılay, earlier during the day: About a dozen left-wing students on a sit-in protest against self-paid university education as their amateurish placards and more amateurish slogans told passers-by. They were surrounded by literally hundreds of policemen anxiously waiting for one single word against the prime minister so that they could “remove the students.” I know the East Germans did not have the liberty to protest, but blame the slight nuance on the fact that Turkey in the year 2011 is not in the Iron Curtain club; it is a European Union member candidate.

Last week, in Ankara’s Keçiören district where Mr. Erdoğan was to make a public speech, his bodyguards noticed a big banner decorating the façade of a building. It simply read: “Esteemed Prime Minister. Did you come by metro, for which you had broken the ground eight years ago? Signed: The locals of Keçiören.”

Apparently, some locals of this overwhelmingly pro-Justice and Development Party and pro-Nationalist Movement Party, or MHP, district were politely protesting the unfinished metro line. No insults. No racist propaganda. Most importantly, nothing illegal in the script. The protest message even addressed Mr Erdoğan in the most cordial way possible in Turkish: Esteemed Prime Minister. But the Turkish Stasi was clever enough to notice the sarcasm, and they forcefully brought down the banner.

Shortly before that, the Stasi had successfully filmed and identified 12 of about 100 journalists who marched to protest the detention of journalists Nedim Şener and Ahmet Şık. The journalists had merely peacefully marched and demanded their colleagues’ release. Now they must pay a fine for that as tickets issued by the governor’s office tell them to do: 154 Turkish Liras each.

And at the weekend, locals in the city of Adapazarı saw a political banner covering the façade of a building on one of the town’s busiest streets. Crafted by the local MHP branch, the banner was a collage of photos, all publicly available, well-known and legal.

The photos showed a pro-Kurdish deputy slapping a police officer on the face, available in all newspaper archives, the parade-like entrance from the Habur border gate of PKK members, available in all newspaper archives, one public remark by the prime minister, available in all newspaper archives, an AKP deputy visiting Diyarbakir’s pro-Kurdish mayor, Osman Baydemir, available in all newspaper archives, and the remains of a city bus in Istanbul after a Molotov cocktail attack by PKK sympathizers, also available in all newspaper archives.

But the Turkish Stasi cleverly thought that when all these legal photos are brought together in an ugly collage for a political message they suddenly became illegal. Naturally, the police forcefully removed the banner from the building without a court order. Last year, a similar photo had been removed from another building in the Hendek Township on orders from the local election board before the Sept. 12 referendum. None of that should be surprising in a country where the prime minister a few years ago sued a lady who received a prison sentence because she had held out a placard that read: Who’s prime minister are you?

I am not sure if the Turkish version operates a branch similar to Stasi’s famous Division for Garbage Analysis, which was responsible for analyzing garbage for any suspect western food and/or material. But Mr. Erdoğan’s Turkey in the year 2011 certainly looks inspired by Stasi’s two other divisions: Main Administration for Struggle Against Suspicious Persons, and the famous Administration 12, which was responsible for the surveillance of mail and telephone.

But Turkey in the year 2011 is certainly different from the GDR four decades ago. No East German company could dare put out newspaper advertisements that appealed to “politicians, high-ranking bureaucrats and businessmen” with a view to marketing its state-of-the-art products that blocked and jammed bugs, listening devices and hidden camera recorders. “Devices for your full safety are available,” the Turkish ads read on the same day a news article in daily Habertürk told of ‘politicians’ rushing to private detective offices in Ankara.” Two bugs were found, the article said, one hidden in a TV set, the other inside the alarm system.

via Democratic Police Republic of Turkey – Hurriyet Daily News and Economic Review.

Leave a Reply