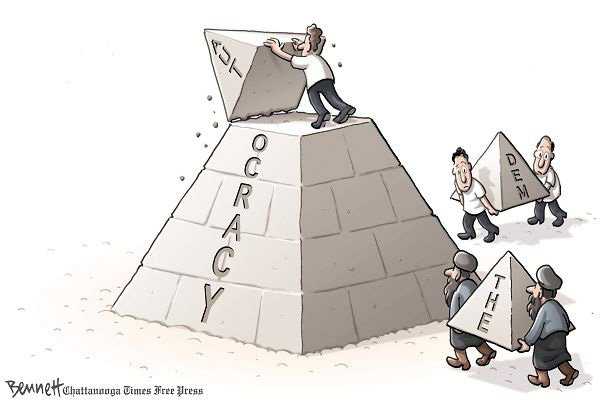

JUST AT the moment that Turkey is being held up as a model for Arab states emerging from authoritarianism, its claim to be the Muslim world’s leading democracy is in danger. Don’t take it from us: Here is what the country’s president, Abdullah Gul, has to say: “The impression I get is that there are certain developments that the public conscience cannot accept. This is casting a shadow over the level that Turkey has reached and the image that is lauded by everyone.”

Mr. Gul was referring to the arrests last week of nine journalists and writers – at least seven of whom were subsequently jailed on charges of involvement in a coup plot against the moderate Islamist government of Mr. Gul’s Justice and Development (AK) party. That the president would publicly express concern shows that Turkey is still a ways from becoming the authoritarian regime that its domestic and foreign critics describe. But it is clearly headed in the wrong direction.

The recent arrests are a good example of what sometimes looks like an assault on liberal democratic values. Four of the journalists work for an anti-government news Web site whose owner was arrested last month; two others were prominent investigative journalists whose work made authorities uncomfortable. One was working on a book about the alleged penetration of security forces by a hard-line Islamist group.

All are charged with participating in a shadowy conspiracy called Ergenekon, which allegedly plotted to overthrow the AK government. Since 2007, more than 400 suspects have been arrested or put on trial in the steadily expanding investigation – including more than one-tenth of the serving generals in the Turkish army as well as academics and politicians from the secular establishment that ruled Turkey before the AK came to power in 2002. Turkey’s journalist association says that 58 journalists have been imprisoned and that thousands could face charges.

There’s no question that some generals, judges and others hoped to force the AK from power by undemocratic means. But there are also abundant indications that the prosecutors pursuing the Ergenekon investigation are overreaching. Much of the evidence they have marshaled looks flimsy and even fabricated. When journalists point out the weaknesses in the case or protest the arrest of their colleagues, the investigators take this as evidence that they, too, have joined the supposed plot.

It’s good that Mr. Gul spoke up. But the real power is Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who does not seem discomfited by the media crackdown. Claiming that his government has nothing to do with the prosecutions, Mr. Erdogan nevertheless hotly criticized U.S. Ambassador Francis J. Ricciardone Jr. when he questioned arrests of journalists last month, calling him – incorrectly – a “rookie” ambassador who knew nothing about Turkey.

Properly, the State Department backed Mr. Ricciardone and said again last week that the Obama administration has “concerns about trends in Turkey.” Mr. Erdogan, who doesn’t hide his ambitions for regional and even global leadership, ought to be concerned as well. If Turkey ceases to become a functioning democracy with unquestionably free media, neither Arab states nor anyone else will look to Turkey as a mentor.