|

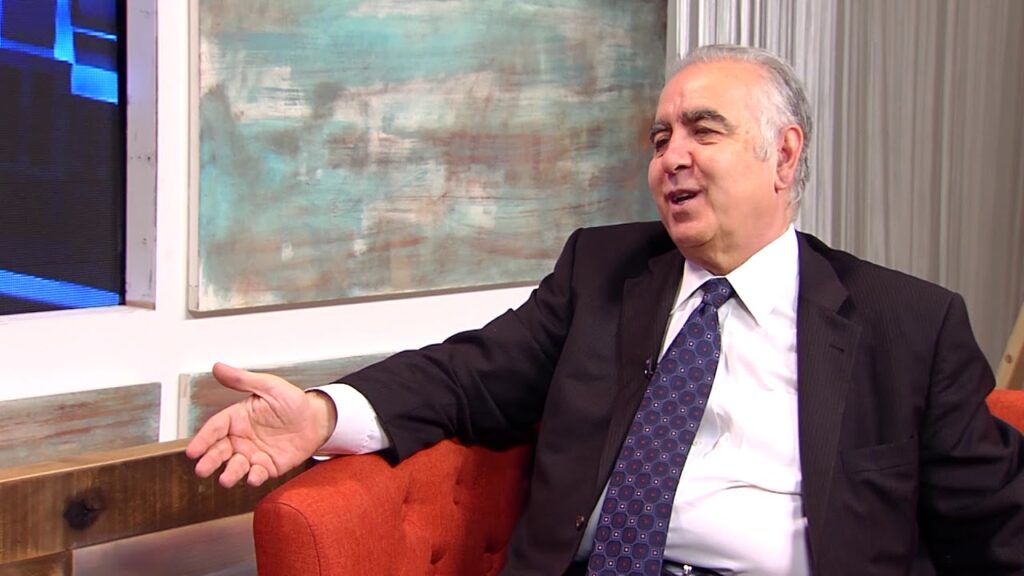

By Harut Sassounian Publisher, The California Courier Two recent documents from Istanbul shed new light on violations of minority rights in Turkey. The authors of these reports make cautious, yet accurate assessments of the problems facing the Armenian, Greek and Jewish communities. The first document, dated February 2011, is titled: “Report on non-Muslim Minorities.” It is written by three well-known Istanbul Armenians: Krikor Doshemeciyan, Yervant Ozuzun, and Murat Bebiroglu. The authors’ stated aim is to seek solutions to the problems of minority populations in Turkey, at a time when the government is planning to revise the constitution to bolster its chances of joining the European Union. Even though the writers do not indicate as to whether their report has been submitted to Turkish officials, the authorities undoubtedly are aware of its contents. It has been posted in Turkish on the Istanbul-based hyetert.com website. The main points of the report are presented below in translation: The authors trace the difficulties facing the non-Muslim minorities to the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 as a monolithic, homogeneous state based on a single culture and religion. This policy had serious consequences for the minorities, forcing them to flee or be assimilated. The non-Muslim minorities were viewed either as foreigners or internal enemies of the state. One cannot find a single policeman or officer who is a member of a minority group. The 1934 displacement of the Jews of Thrace, the exorbitant 1942 Wealth Tax on minorities, and the large-scale attacks on Greeks in Istanbul on Sept. 6-7, 1955, resulted in the impoverishment of these communities and the devastation of their culture. Such discriminatory policies and brutal attacks led to a significant decrease in Turkey’s minority population from 350,000 in 1927 to 80,000 today, while the number of Turks increased six-fold. The writers point out that the Turkish government has recently returned a few of the properties belonging to minority institutions that were confiscated starting in 1974. Due to contradictions and shortcomings in the new law on minority foundations, the returned properties can not be put to good use, because none of the communities are allowed to repair them. The government has further violated Articles 41 and 42 of the 1923 Lausanne Treaty which obligated Turkey to provide funding and facilities to non-Muslim minorities for educational, religious, and charitable purposes, and to protect their religious establishments. Beyond the Lausanne Treaty, several provisions of UN conventions and the European Convention on Human Rights are continuously violated by the Turkish government. One of the most serious problems facing these minorities is the Turkish government’s non-recognition of the Armenian Patriarchate and the Jewish Rabbinate as legal entities. The Greek Patriarchate was finally recognized as a legal entity last year. Another problem is the government’s appointment of Turkish Vice Principals to oversee minority schools which causes deep mistrust. The preparation of new teachers and clergymen has also become impossible due to the closing down of religious seminaries by the Turkish state. The writers of the report request that clergymen be allowed to teach religion in minority schools, as they had done previously. In conclusion, the authors urge the Turkish authorities to take into account all of the foregoing legal issues when drafting a “democratic and modern” constitution. The second document is an interview conducted by Agounk Center’s Meline Anoumyan with Archbishop Aram Ateshian, Vicar General of the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul, as the Patriarchate is preparing to celebrate its 550th anniversary. According to Abp. Ateshian, 67,000 Armenians live in Istanbul, while another 3,000 reside in the country’s interior — 500 in Ankara, 300 in Iskenderoun, 70 in Sepastia, 50 in Malatia, and 20 families in Kharpert. In addition, the Vicar General revealed that there are 100,000 Armenians in Turkey who fear disclosing their true identity. This figure does not include the undocumented workers from Armenia who are not allowed to get married and whose children cannot be baptized by the Patriarchate due to their illegal status. Abp. Ateshian is pleased that a few of the confiscated properties have been returned to Armenian foundations in recent years. He disclosed that there are 44 functioning Armenian Apostolic churches in Turkey — 37 in Istanbul, 3 in Iskenderoun, 2 in Dickranagerd, 1 in Mardin, and 1 in Gessaria. In addition, there are 12 Armenian schools associated with the Patriarchate, and Armenian Catholics have 3 schools and 10 churches. A total of 3,000 Armenian Catholics and 1,000 Armenian Protestants live in Turkey. It is encouraging that after nine decades Armenian religious and lay leaders in Istanbul have mustered enough courage to raise their voices in defense of their violated civil rights! |