He who loves the rose should put tip with its thorns.

—Old Turkish saying

ONE day in 1853, Nicholas I, Czar of all the Russias, peered southward over his aristocratic nose and voiced the opinion that Turkey was indeed “the sick man of Europe.” Exactly 100 years later, an astute and wealthy Texan named George McGhee, at the time U.S. Ambassador to Turkey, looked out over the green plains of Anatolia and said: “You know what this country reminds me of? It’s got the stuff, the git up and go, and it’s rolling. Why, Turkey today is just like Texas in 1919.”

Both Czar and ambassador had it right. In one century, the sick man of Europe has become the strong man of the Middle East. If not the paradise that propagandists sometimes paint, Turkey is stable, strong, democratic, progressive, booming. No nation stands so steadfast against Russia. In NATO it is the free world’s strong southern anchor; in the Korean war, its brigade was the “BB Brigade,” the Bravest of Brave. Turkish landing fields put U.S. strategic air half an hour away by jet from the Baku oilfields of Russia.

Assisted by U.S. dollars and skill, but doing its own hard work and running its Own show, Turkey is increasing its per Capita income 7% per annum, its gross national product 10%. As recently as 1950, Turkey had to import wheat; today she is the No. 4 wheat exporter in the world. In the same three years, Turkey’s tractors increased by 900%, farm acreage 25%, mileage of all-weather roads 100%, port capacity 250%, cotton output 300%. Yet these are the people of whom the Bulgar peasant used to say, making the sign of the cross: “No grass grows where the Turk’s horse treads.”

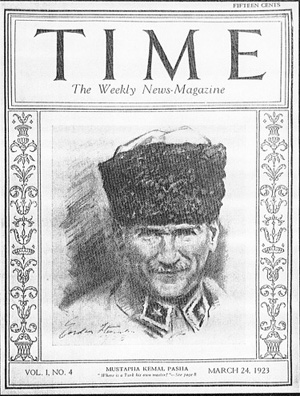

Ruthless Miracle. What brought the change? Between the days of the sick man and the Texas-style Turkey of today, the nation brought forth Kemal Ataturk. He worked his miracle, closed history’s gap in just 15 years, 1923-1938, and died 15 years ago next month.

By conventional standards, Kemal Ataturk was hardly an admirable character. He was a bitter, sullen and ruthless man, a two-fisted drinker and a rake given to shameless debauch. Politically, though he proclaimed a Bill of Rights, he flouted it constantly; though he talked of loyalty, he hanged his closest friends. He was devoid of sentiment and incapable of love, unfaithful to everyone and every cause he adopted save one—Turkey. But before he died, his driven, grateful people thrust on him the last and greatest of his five names: Ataturk, Father of All the Turks.

The Father of All the Turks (who left no legitimate heirs) was born in 1881 in Salonika, then part of the Ottoman Empire, of a mild Albanian father and a forceful Macedonian mother. Mustafa was a rebel from the start. His pious Mohammedan mother urged him to become a holy man, but he became a soldier; at 22, a captain, he rebelled against the Sultan and was nearly executed; at 27, he joined the Young Turks rebellion, then rebelled against the Young Turks. The army, fearful of him, shunted him from post to post, but could neither shake him nor subdue him. At Gallipoli, in 1915, he defeated the British; in the Caucasus, he checked the Russians; in Berlin, 1918, he drunkenly needled the high panjandrum of his allies, Field Marshal von Hindenburg; in Arabia, 1918, he held off T. E. Lawrence’s Bedouin hordes. At 38, he came out of the crash of the Ottoman Empire the only Turkish commander untouched by defeat.

Six Day Marathon. Eight years later, smartly turned out in his favorite civilian attire—the morning coat and striped pants of the Western diplomat—he stood before the Turkish National Assembly (which he created), in the capital at Ankara (which he created), and for six full days told in the Turkish language (which he purified and revised) the full story of what he had done. He began:

“Gentlemen, I landed at Samsun on the 19th of May, 1919. This was the position at the time…”

To his hearers, it was well-remembered history. Turkey in 1919 was crushed, defeated from without, disintegrating within. Gone was the fury and might which, beginning in 1299, had sent Ottoman legions smashing at Vienna’s gates and made Budapest a suburb of Constantinople. Gone was the conquering fervor that created a tri-continental empire the size of the U.S., encompassing what are now 20 modern nations stretching from the Dniester to the Nile, from the Adriatic to the Persian Gulf. In 1919, British warships still rode in the Bosporus and British troops held Constantinople; Italy, France and Greece were secretly dividing up the best of the remainder. The greatest empire between Augustus and Victoria had shrunk to a small, lifeless inland state in the barren interiors of Asia Minor; its Sultan was reduced to the status of a borough president of Constantinople. There was talk of asking Woodrow Wilson to take over the mess as a U.S. mandate.

Mustafa Kemal Pasha returned from his skillful but useless defense of Syria and asked for a job. “Get this man away—anywhere—quickly,” the Sultan cried. The government hoped to save itself by submission to the conqueror; Kemal’s unyielding patriotism endangered these schemes. So Mustafa got magnificent and meaningless titles—Inspector General of the Northern Area and Governor General of the Eastern Provinces—and was put aboard a leaky Black Sea steamer bound for Samsun, in remote Anatolia.

This suited Kemal fine. Arriving in Anatolia, he convoked a congress and proclaimed: “The aim of the movement is to free the Sultan-Caliph from the clutches of the foreign enemy.” Desperately, the Sultan, who did not want to be so freed, wired: “Cease all activity!” Replied Kemal: “I shall stay in Anatolia until the nation wins its independence.” Turkey, or what was left of it, had two governments: Kemal’s and the Sultan’s.

The victorious Allies, of course, favored the complaisant Sultan, but in their greed they served to further Kemal. The Sultan and the Grand Vizier went to Versailles to plead not to be denuded of all land and power. Clemenceau, the Tiger, said coldly: “Be silent, Your Highness! Relieve Paris of your presence.” The Allies handed the Sultan the Treaty of Sevres, which split Turkey six ways. The Greeks marched in to enforce the Diktat, and Kemal roared: “Turks! Will you crawl to these Greeks who were your slaves only yesterday?” He raised an army of peasants, veterans, criminals, patriots. Two years later, a few miles outside of Ankara, he gave the orders: “Soldiers, the Mediterranean is your goal,” and drove the Greeks back into the sea.

The Treaty of Lausanne which followed reversed the humiliation of Sevres. The last British admiral boarded the last British battleship in the Bosporus, snapped a respectful salute to the crescent flag and steamed off. The most defeated of enemies became the first to defy the victorious Allies, to scrap one of their treaties. The Ataturk miracle had begun: Mustafa Kemal, soldier, was master of Turkey.

Only Turks. The nation he put back together was slightly larger than Texas—296,000 sq.mi.—its vast bulk nestled in Asia Minor, with 9,000 sq.mi. wedging into Europe’s southeastern corner. Kemal was satisfied. “We are now Turks—only Turks,” he exulted. He wanted none of the old overextended Ottoman empire. “Away with dreams and shadows; they have cost us dearly,” he said.

Kemal went on a speaking tour among his people: “Remain yourselves, but take from the West that which is indispensable to the life of a developed people. Let science and new ideas come in freely. If you don’t, they will devour you.”

He began taking from the West, but he took with discrimination. He wanted to democratize Turkey, for “no country is free unless it is democratic.” But he recognized that “Democracy in Turkey now would be a caricature,” and set his dictatorship to preparing his nation for democracy. Thirty years ago this month (on Oct. 29, 1923), Kemal became: President of the new republic, commander in chief of the army, president of the Council of Ministers, chief of the only party, and speaker of the Assembly. He began ridding the Turks of the things that reminded them of the degenerate past. First he ordered the Sultan expelled; 16 months later the Caliph (or Moslem spiritual leader) was exiled. Kemal announced that “Islam is a dead thing,” and Turkey became a nondenominational state.

The break with the past had to be felt, simply and simultaneously, by all Turks. Ataturk looked about for the significant gesture. In India it had been salt-making in defiance of the British monopoly; in China it was cutting off the queue. Ataturk chose to attack the fez, traditional symbol of Ottoman citizenship. “The fez is a sign of ignorance,” said he. He laid down a deadline: after that date, no brimless headgear. Some Turks, unable to find hats with brims, wore their wives’ hats: better to look silly than to risk losing your head.

Coffee fo Kahve. Ataturk moved the capital from cosmopolite Constantinople to raw Ankara and changed Constantinople’s name to Istanbul. Though he personally abhorred emancipated women (they argued, instead of saying yes), he begged Turkey’s women to unveil, and most did. He abolished the Moslem sheriat (law) and took the best from Europe to replace it—Switzerland’s civil code, pre-Fascist Italy’s penal code, Germany’s commercial code.

Though he made haste, he had an intuitive awareness of his people’s gait. The old Turkish alphabet had become an esoteric nightmare of cumbersome Arabic scrawls; its difficulty contributed to illiteracy at home and incomprehensibility abroad. Kemal talked first to U.S. Educator John Dewey, then sat down with linguistic experts and worked out a new, simple Latin, A-B-C alphabet of 29 letters. Where new concepts lacked ancient symbols, he simply used Western forms: automobile to otomobil; coffee to kahve; statistic to istatistik.

Blackboards went up in the National Assembly, and Kemal himself gave the Deputies their first lesson. He went to the countryside and guided the gnarled hands of peasants who had never held a pencil before, as they wrote clumsy signatures in the new script. This patient teaching took five years; then abruptly he switched from precept to fiat. He gave civil servants three months to master the new script—or find new jobs. He had not been to Istanbul since 1919; now he returned in style and with a purpose. He sailed into the Golden Horn on the Sultan’s yacht, triumphantly marched past cheering crowds. He summoned Istanbul’s elite to the Sultan’s palace to a ball, and stood before them in full evening dress on a raised platform, chalk in hand, before a blackboard. For two hours he explained the new language, then the music blared, everyone drank, and the dancing went on until dawn. Nineteen twenty-eight became the Year One of Turkey’s new cultural life.

Oy Birligile. Ataturk liberated law, education and marriage from the mullahs; turned mosques into granaries; switched the day of rest from Friday to Sunday; tossed out the Islamic calendar and ordered in the Gregorian calendar of the Western world. He made suffrage universal, adopted the metric system, ordered all Turks to take on last names, took the first census in Turkish history. Harems were forbidden and monogamy became the law.

The most familiar phrase in the Turkish National Assembly during these electric days was Oy Birligile, meaning by unanimous vote. Opposed, Ataturk was ruthless. One evening in 1926, he gave a champagne party for foreign diplomats; it turned into an all-night carousal. Returning home at dawn, the diplomats saw the corpses of the entire opposition leadership, among them Kemal’s old friends, hanging in the town square.

But in his later years, after he had raised his people up, he decided to ease his dictatorship. He brought his ambassador home from France, ordered him to head an opposition, ordered his own sister to join it. The new Liberal Republican Party was so polite at first that Kemal demanded more vigor; when it became more vigorous he abolished it. “Let the people leave politics for the present,” he said. “Let them interest themselves in agriculture and commerce. For ten or 15 years more I must rule.”

After Ataturk. He did not have ten or 15 years more. Since his teens he had been drinking and whoring, searching, without finding, some personal peace. He tried marriage once in 1922 to Latife, the daughter of a Smyrna shipowner, but was soon divorced. In 1938, exhausted by periodic debauches and drinking bouts, undermined by diseases, he died. The timing was just right. Kemal Ataturk had held the Turks by the hand just long enough to help, not long enough to crush.

The day after Ataturk’s death, he was succeeded as President, legally and peacefully, by his handpicked successor, forceful soldier-administrator Ismet Inonu. For the next dozen years, the Inonu regime tried to maintain the Ataturk pattern. The people were kept on short rein, given few civil and personal liberties, and those grudgingly. But the momentum of progress continued.

In 1946, the Ataturk-Inonu party, the Republican People’s Party, won reelection, but only by using shabby tactics. It was the last time. A new, politically conscious opposition had grown up. Ataturk had unleashed forces greater than he; he had made so many new Turks that there was bound to be a new Turkey. In 1950, 88% of the voters went to the polls and swept out the Republican People’s Party which had held power uninterruptedly for 27 years. Inonu yielded gracefully. The newborn Democrats took over.

Their President was unspectacular Celal Bayar, an able banker and one of Ataturk’s ministers for five years, his Premier for one. This peaceful transfer of power was not the millennium, but it was the closest approach to it in the Middle East. Ataturk’s 15 years of ruthless education and preparation had paid off.

“Black Danger.” The new regime put an end to excessive state regulation of business. Ataturk had tried to industrialize Turkey through a cumbersome form of state socialism that he labeled étatisme. He developed some industry, but stifled it in red tape and scared away foreign investors. Now, under Bayar, Turkey is one of the few nations in the world heading towards more, not less free enterprise. Foreign investors are encouraged. There have been other reversals of Ataturk policy. Many emancipated Turks now fear “the black danger,” the resurgence of the once powerful mullahs. Religion is strong today in Turkey. The country is 98% Moslem. Ataturk relaxed the grip of a reactionary and decadent church, but he could not destroy the faith of his people. Just as Ataturk had taken the best from them, discarded the rest, the Turks are showing a talent for preserving what they think best in his teaching.

Turkey today is still far from Ataturk’s goals: 80% of its 21 million people live in mud huts in isolated villages, in half of which there are no primary schools. The currency is soft; inflation has doubled food prices. Much of the land is unfertilized and carelessly utilized. The Turk is poor: he gets a third of the meat that a meat-starved Briton received under austerity; only one in 2,000 owns an automobile. But Turkey’s spirit is good, the country is stable, its directon is sound.

A month hence, Ataturk’s body, which has lain in a “temporary” resting place these past 15 years, will be borne with ceremonial pomp to a new mausoleum on Ankara’s highest hill. The mausoleum, reached by 33 marble steps 132 feet wide, will probably be the biggest of its kind, until Evita Peron’s or the proposed Soviet pantheon tops it. For three days, Turkey’s 21 million citizens will do him honor.

“I will lead my people by the hand along the road until their feet are sure and they know the way,” Ataturk had said. “Then they may choose for themselves and rule themselves. Then my work will be done.” On his bronze statue overlooking the Golden Horn is another message to his people: “Turk! Be proud, hardworking and self-reliant!”

- Find this article at:

Leave a Reply